There’s trouble in Park City, with a capital T and that rhymes with C and that stands for COVID. (Sorry, but I am just dying to see the new “Music Man” on Broadway.) Canceling this year’s in-person Sundance Film Festival created plenty of headaches — grousing about non-refundable condos and passes abound — but in its shadow is another, much larger disappointment that has the capacity to undermine regional film festivals and the organizations that support them.

Under the federal government’s American Rescue Plan to aid economic recovery from the pandemic, the National Endowment for the Arts received funding for grants to support operating costs at arts organizations. Nearly 600 festivals and film organizations applied for the competitive grants, offered in tiers of $50,000, $100,000, and $150,000. This week, the rejection letters started rolling in.

I don’t expect Netflix to lose sleep over the skeleton crews that run beloved local festivals from Seattle to Philadelphia, where non-profits struggle to make rent and hold on to their staffs. However, audiences who want entertainment choices that go beyond algorithms should pay attention. Community and quality are hard to quantify in the film world, and require acute programming instincts to serve. If you’re sick of the most obvious home viewing options, your local festival has your back. Smart, engaged movie audiences depend as much on small-scale festivals as the heavyweights.

And the government can’t help them all. As the NEA’s form letters noted, only seven percent of more than 7,500 applicants scored funding. The NEA asked funded organizations not to reveal their status until a later date; a rep for the government body said the recipients would be announced “later this month.”

“We understand this is disappointing news, especially in light of the challenges the COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose for the nation’s arts community,” the NEA wrote to applicants. “We recognize a substantial amount of effort is invested in each application, and that your organization and many others are working diligently to keep staff members and artists paid, doors open, and the arts central to our daily lives.”

The grants on offer do not sound like life-altering sums — they range from $50,000 to $150,000 — but we’re talking about nonprofits where a programming initiative that puts them in the black by a few thousand bucks is a winning case study. Meanwhile, the Art House Convergence — the annual gathering of independent exhibitors who meet in the run-up to Sundance — postponed for a second year in a row as its beleaguered organization eyes an ambitious reboot by the end of 2022.

Like the scrappy artists these organizations curate, these lo-fi entities thrive in survival mode. Current circumstances are much closer to crisis. Americans for the Arts reported that pandemic-related layoffs and closures cost the arts sector close to $14 billion in 2020. Virtual events attracted a lot of quarantined moviegoers, but that effect has started to erode. At the recent online FilmEx conference this past week, several regional festival leaders observed a dropoff in interest for virtual screenings and events — not that they yielded much in the way of profit in the first place.

Most nonprofit film organizations don’t treat money as a primary metric; they measure success by their ability to create and curate programming that retains local audiences. It’s a business model that doesn’t operate on the same plane as Sundance’s multimillion-dollar deals, but without the support of those humble organizations, it’s hard to imagine a future for movies beyond tentpoles.

Among those who didn’t make the NEA cut is Film Pittsburgh; executive director Katherine Spitz Cohan said it intended to use the grant for two of its film programs: “Teen Screen,” a free educational field trip program for middle and high school students, and ReelAbilities Pittsburgh, a film festival centered on people living with disabilities.

“We are hopeful to still present both programs,” she said. “They are unique and well-received in our region. We are able to do so because we have generous, long-time support from several foundations here in Pittsburgh.” She added that the NEA supported the organization through additional arts funding to the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.

Another disappointed party was The Luminal Theater, a nomadic programming entity that curates Black cinema for festivals in addition to year-round programming nationwide. “Although we were rejected for the ARP grant, which is heavy, the NEA has been good to us as far as a prior grant and the management of it all,” said curator Curtis John. “We’re still planning ’22 out.”

He plans to hold the in-person Caribbean Film Series at BAM in February, but said the grant rejection makes “even half-dream planning next to impossible.” He saw some success curating virtual shorts programs last year, but less so for features. “For first-run indies, our arthouse friends have higher marketing budgets and sometimes bigger mailing lists, so they have higher success than we do with those films,” John said.

In December 2021, Sundance quietly agreed to serve as fiscal sponsor for AHC for the next year. Emails circulated this week among members of the “Art House Convergence Transitional Working Group” about creating a governing board that will be tasked with incorporating the organization as a 501c3, separate from Sundance.

“We’re trying to develop an ecosystem that will celebrate and lift up the films that tell the stories of folks whose stories have not been told,” said AHC transitional committee member Camille Blake Fall, who also serves on the board of the Maryland Film Festival. “It will now operate through the lens of equity, inclusion, diversity, and will attempt to help urban arthouses really center voices that have not been centered.”

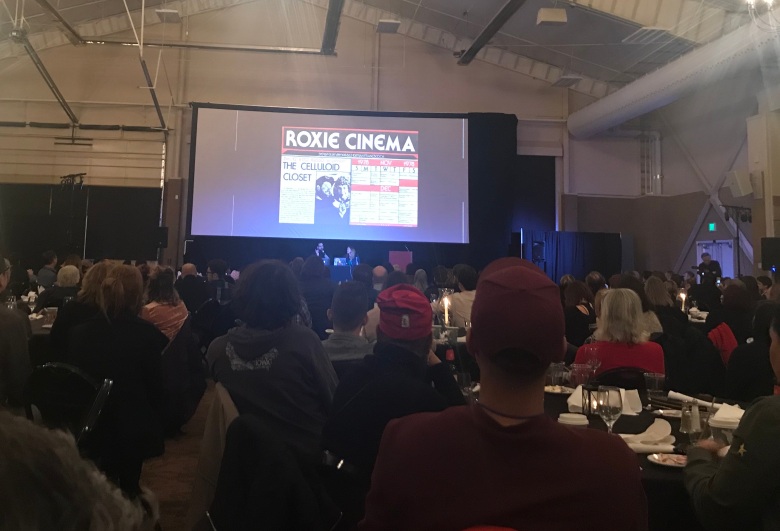

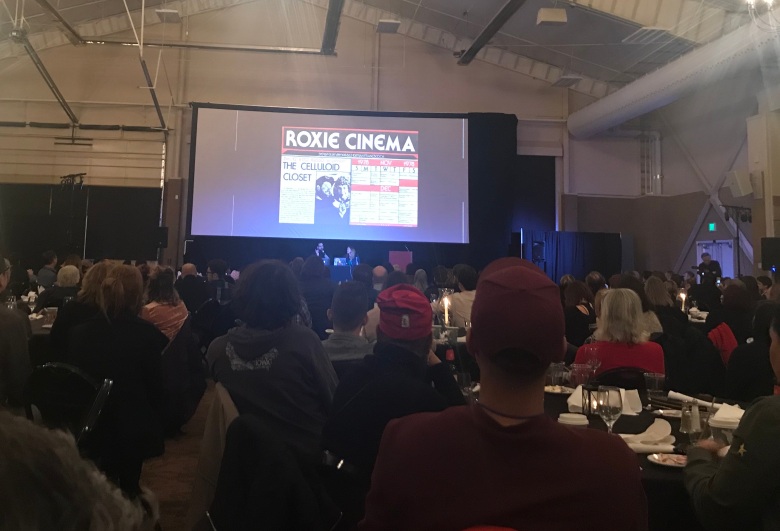

A presentation at the 2018 Art House Convergence

For a few years, I attended the Maryland Film Festival’s day-long “Filmmakers Taking Charge” event, a fascinating off-the-record gathering for filmmakers largely working outside of the studio system to swap intel. Filmmakers looking for footing beyond the hope of selling a movie for millions at Sundance and scoring a studio deal need more opportunities like this. In the process, audiences that want to be engaged by more than the biggest blockbusters will turn to local festivals for guidance. These viewers don’t have to number in the millions to make a difference.

This nuance — how small, engaged, local-level audiences support the future of cinema — gets lost in broader conversations about how movies resonate in the marketplace.

In last week’s column, I argued that VOD was a critical factor in sustaining unconventional movies; some industry readers took issue. “Outside of awards chasing, the big SVODs are seemingly turning their backs on true indie films,” one specialty distributor wrote me. He noted that the weekly VOD viewing charts illustrate how “the big SVOD players are often backing away from small indies after having flirted with them when they were building viewership and scaling up.”

Fair enough. Those numbers, however, only tell part of the story about what an engaged arthouse audience looks like in 2022. Sundance’s program of 80-odd feature films is small and exclusive; where do the countless other movies go, and the audiences hungry for more? Watching a FilmEx panel on virtual marketing, I was struck by a comment made by Mel Rodriguez, who runs the Horrible Imaginings Film Festival supported by the Media Arts Center San Diego. “What do we offer that Netflix doesn’t?” he asked. “We need some element of this being exclusive and some of it being an event as well as a little bit of flexibility because people at home just do not watch films the same way they do in the cinema.”

Much of the tone at FilmEx was the sort of rah-rah communal celebration that non-profits tend to tout in defense mode. FilmEx sponsor Eventive, which many regional festivals use as a screening platform for virtual programs, served over 3.5 million unique visitors last year. “That hunger for community is growing as we enter this new normal of hybrid festivals, virtual events, pulling these things together,” said Eventive co-founder Iddo Patt.

That hunger can also taper in the face of pandemic fatigue and a million streaming options. Big streamers like Netflix and Amazon have supported Sundance, Toronto, and Telluride, but the true support system for an independent film culture comes from individual engagement. Even Netflix and its ilk benefit from the discovery of unique work with the potential to go far. Financing entities might consider how even a very modest contribution goes a long way to supporting the needs of small festivals.

I’m reminded of the grassroots activism of an election year, when even the tiniest commitment — in this case, engaging with a local screening series one movie at a time, or even just subscribing to a film society’s newsletter — makes a difference. These niche organization foster micro-budget filmmaking and challenging visions. It’s time to step up, movie people: What are you doing to support your local film programming? The answer to that question matters more than you think.

Of course, I could be falling into the same naive trap of any organization that overemphasizes communal engagement over more precise business solutions to its problems. As usual, I encourage readers to reach out with feedback, to correct the record or suggest other strategies…or to call me an idiot, as long as you can back it up: eric@indiewire.com

Under the federal government’s American Rescue Plan to aid economic recovery from the pandemic, the National Endowment for the Arts received funding for grants to support operating costs at arts organizations. Nearly 600 festivals and film organizations applied for the competitive grants, offered in tiers of $50,000, $100,000, and $150,000. This week, the rejection letters started rolling in.

I don’t expect Netflix to lose sleep over the skeleton crews that run beloved local festivals from Seattle to Philadelphia, where non-profits struggle to make rent and hold on to their staffs. However, audiences who want entertainment choices that go beyond algorithms should pay attention. Community and quality are hard to quantify in the film world, and require acute programming instincts to serve. If you’re sick of the most obvious home viewing options, your local festival has your back. Smart, engaged movie audiences depend as much on small-scale festivals as the heavyweights.

And the government can’t help them all. As the NEA’s form letters noted, only seven percent of more than 7,500 applicants scored funding. The NEA asked funded organizations not to reveal their status until a later date; a rep for the government body said the recipients would be announced “later this month.”

“We understand this is disappointing news, especially in light of the challenges the COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose for the nation’s arts community,” the NEA wrote to applicants. “We recognize a substantial amount of effort is invested in each application, and that your organization and many others are working diligently to keep staff members and artists paid, doors open, and the arts central to our daily lives.”

The grants on offer do not sound like life-altering sums — they range from $50,000 to $150,000 — but we’re talking about nonprofits where a programming initiative that puts them in the black by a few thousand bucks is a winning case study. Meanwhile, the Art House Convergence — the annual gathering of independent exhibitors who meet in the run-up to Sundance — postponed for a second year in a row as its beleaguered organization eyes an ambitious reboot by the end of 2022.

Like the scrappy artists these organizations curate, these lo-fi entities thrive in survival mode. Current circumstances are much closer to crisis. Americans for the Arts reported that pandemic-related layoffs and closures cost the arts sector close to $14 billion in 2020. Virtual events attracted a lot of quarantined moviegoers, but that effect has started to erode. At the recent online FilmEx conference this past week, several regional festival leaders observed a dropoff in interest for virtual screenings and events — not that they yielded much in the way of profit in the first place.

Most nonprofit film organizations don’t treat money as a primary metric; they measure success by their ability to create and curate programming that retains local audiences. It’s a business model that doesn’t operate on the same plane as Sundance’s multimillion-dollar deals, but without the support of those humble organizations, it’s hard to imagine a future for movies beyond tentpoles.

Among those who didn’t make the NEA cut is Film Pittsburgh; executive director Katherine Spitz Cohan said it intended to use the grant for two of its film programs: “Teen Screen,” a free educational field trip program for middle and high school students, and ReelAbilities Pittsburgh, a film festival centered on people living with disabilities.

“We are hopeful to still present both programs,” she said. “They are unique and well-received in our region. We are able to do so because we have generous, long-time support from several foundations here in Pittsburgh.” She added that the NEA supported the organization through additional arts funding to the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.

Another disappointed party was The Luminal Theater, a nomadic programming entity that curates Black cinema for festivals in addition to year-round programming nationwide. “Although we were rejected for the ARP grant, which is heavy, the NEA has been good to us as far as a prior grant and the management of it all,” said curator Curtis John. “We’re still planning ’22 out.”

He plans to hold the in-person Caribbean Film Series at BAM in February, but said the grant rejection makes “even half-dream planning next to impossible.” He saw some success curating virtual shorts programs last year, but less so for features. “For first-run indies, our arthouse friends have higher marketing budgets and sometimes bigger mailing lists, so they have higher success than we do with those films,” John said.

In December 2021, Sundance quietly agreed to serve as fiscal sponsor for AHC for the next year. Emails circulated this week among members of the “Art House Convergence Transitional Working Group” about creating a governing board that will be tasked with incorporating the organization as a 501c3, separate from Sundance.

“We’re trying to develop an ecosystem that will celebrate and lift up the films that tell the stories of folks whose stories have not been told,” said AHC transitional committee member Camille Blake Fall, who also serves on the board of the Maryland Film Festival. “It will now operate through the lens of equity, inclusion, diversity, and will attempt to help urban arthouses really center voices that have not been centered.”

A presentation at the 2018 Art House Convergence

For a few years, I attended the Maryland Film Festival’s day-long “Filmmakers Taking Charge” event, a fascinating off-the-record gathering for filmmakers largely working outside of the studio system to swap intel. Filmmakers looking for footing beyond the hope of selling a movie for millions at Sundance and scoring a studio deal need more opportunities like this. In the process, audiences that want to be engaged by more than the biggest blockbusters will turn to local festivals for guidance. These viewers don’t have to number in the millions to make a difference.

This nuance — how small, engaged, local-level audiences support the future of cinema — gets lost in broader conversations about how movies resonate in the marketplace.

In last week’s column, I argued that VOD was a critical factor in sustaining unconventional movies; some industry readers took issue. “Outside of awards chasing, the big SVODs are seemingly turning their backs on true indie films,” one specialty distributor wrote me. He noted that the weekly VOD viewing charts illustrate how “the big SVOD players are often backing away from small indies after having flirted with them when they were building viewership and scaling up.”

Fair enough. Those numbers, however, only tell part of the story about what an engaged arthouse audience looks like in 2022. Sundance’s program of 80-odd feature films is small and exclusive; where do the countless other movies go, and the audiences hungry for more? Watching a FilmEx panel on virtual marketing, I was struck by a comment made by Mel Rodriguez, who runs the Horrible Imaginings Film Festival supported by the Media Arts Center San Diego. “What do we offer that Netflix doesn’t?” he asked. “We need some element of this being exclusive and some of it being an event as well as a little bit of flexibility because people at home just do not watch films the same way they do in the cinema.”

Much of the tone at FilmEx was the sort of rah-rah communal celebration that non-profits tend to tout in defense mode. FilmEx sponsor Eventive, which many regional festivals use as a screening platform for virtual programs, served over 3.5 million unique visitors last year. “That hunger for community is growing as we enter this new normal of hybrid festivals, virtual events, pulling these things together,” said Eventive co-founder Iddo Patt.

That hunger can also taper in the face of pandemic fatigue and a million streaming options. Big streamers like Netflix and Amazon have supported Sundance, Toronto, and Telluride, but the true support system for an independent film culture comes from individual engagement. Even Netflix and its ilk benefit from the discovery of unique work with the potential to go far. Financing entities might consider how even a very modest contribution goes a long way to supporting the needs of small festivals.

I’m reminded of the grassroots activism of an election year, when even the tiniest commitment — in this case, engaging with a local screening series one movie at a time, or even just subscribing to a film society’s newsletter — makes a difference. These niche organization foster micro-budget filmmaking and challenging visions. It’s time to step up, movie people: What are you doing to support your local film programming? The answer to that question matters more than you think.

Of course, I could be falling into the same naive trap of any organization that overemphasizes communal engagement over more precise business solutions to its problems. As usual, I encourage readers to reach out with feedback, to correct the record or suggest other strategies…or to call me an idiot, as long as you can back it up: eric@indiewire.com