Hi guys,

I've been looking for some clear cut definitions and examples of the different act structures for film but I can't find many explanations in lamens terms. I've found some information but they all seem to have an assumed level of knowledge of which I have next to none.

Is there an FAQ, sticky or any sort of other in depth explanations with examples, and I guess more importantly, "the rules" of the different kinds of act structures floating around, aimed at newbies?

I really would love to be able to dissect a movie while I watch it and know what's what, what's going on and when it's suppose to happen. I can do this for almost all Romantic Comedies as they are generally very formulaic. It's just not always clear for me, I was sure Cool Hand Luke was a two act structure but apparently its 3 act. And Scarface was a two act structure when I thought it was 3.

Anyhoo, I think I know a bit about the rules of the three act structure, but this is all pretty much observations on my part and is probably wrong:

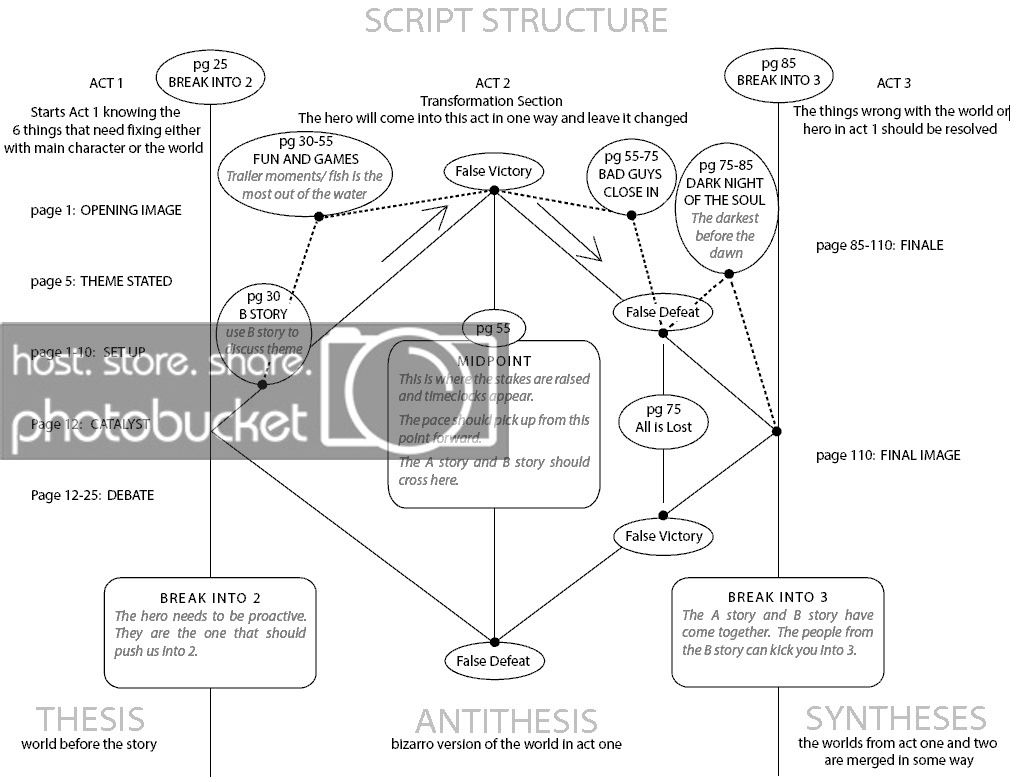

- Act 1 is the set up, 2 is the conflict and 3 is the resolution

- Generally act 2 is twice as long as 1 and 3

- Using a stock standard 2 hour movie as an example: Act 1 would last 30 minutes, with an "event" at about 10 or 15 minutes in that sets the tone of the movie and a glimpse of the conflict, then at about 30 minutes something happens that introduces the actual conflict which starts act 2: A plot twist or something. Act 2 lasts for about 1 hour, IE: the protagonsit searching for someone or something. Then, at the end of act 2 there is some form of "extreme low" for the protaganist, IE: kidnappened, down and out, love interest gone for good etc. Then act 3 starts which is the resolution which builds up to the finale! IE: Protagonist beating the antagonist, find true love etc.

Here is an example of what I think a 3 act structure is using Winter's Bone, it's one movie that I'm sure has a very clear and defined 3 act structure and one of the few that I can dissect:

Don't read if you haven't watched it, there are spoilers!

I'm so sorry for the length of the post, it's just that I really want to understand the different kinds of Act Structures for films as I see it as being instrumental in writing a decent screenplay, I doubt I will even attempt to write one without a sound understanding of this knowledge.

Thanks a lot for reading, and thanks in advance for the replies!

I've been looking for some clear cut definitions and examples of the different act structures for film but I can't find many explanations in lamens terms. I've found some information but they all seem to have an assumed level of knowledge of which I have next to none.

Is there an FAQ, sticky or any sort of other in depth explanations with examples, and I guess more importantly, "the rules" of the different kinds of act structures floating around, aimed at newbies?

I really would love to be able to dissect a movie while I watch it and know what's what, what's going on and when it's suppose to happen. I can do this for almost all Romantic Comedies as they are generally very formulaic. It's just not always clear for me, I was sure Cool Hand Luke was a two act structure but apparently its 3 act. And Scarface was a two act structure when I thought it was 3.

Anyhoo, I think I know a bit about the rules of the three act structure, but this is all pretty much observations on my part and is probably wrong:

- Act 1 is the set up, 2 is the conflict and 3 is the resolution

- Generally act 2 is twice as long as 1 and 3

- Using a stock standard 2 hour movie as an example: Act 1 would last 30 minutes, with an "event" at about 10 or 15 minutes in that sets the tone of the movie and a glimpse of the conflict, then at about 30 minutes something happens that introduces the actual conflict which starts act 2: A plot twist or something. Act 2 lasts for about 1 hour, IE: the protagonsit searching for someone or something. Then, at the end of act 2 there is some form of "extreme low" for the protaganist, IE: kidnappened, down and out, love interest gone for good etc. Then act 3 starts which is the resolution which builds up to the finale! IE: Protagonist beating the antagonist, find true love etc.

Here is an example of what I think a 3 act structure is using Winter's Bone, it's one movie that I'm sure has a very clear and defined 3 act structure and one of the few that I can dissect:

Don't read if you haven't watched it, there are spoilers!

Act 1 introduces the characters and the sparseness of the landscape etc. About 10 minutes in that guy comes and looks for her Dad (the event that sets the tone of the movie: Missing Dad) Then at the end of act 1 she starts looking for her Dad, this is the beginning of act 2. She then spends act 2 looking for him, getting told lies, wild goose chases etc. Then, she gets held against her will and beat up which is the end of act 2 (protagonist extreme low), Then act 3 begins and with her perseverence she is led to her Dad's "grave".

I'm so sorry for the length of the post, it's just that I really want to understand the different kinds of Act Structures for films as I see it as being instrumental in writing a decent screenplay, I doubt I will even attempt to write one without a sound understanding of this knowledge.

Thanks a lot for reading, and thanks in advance for the replies!