We live in strange times. This young century has been defined by harrowing disasters both natural and man-made, political tribalism, and existential threats to the future of the planet. What better time for documentary filmmaking?

Non-fiction cinema has been evolving since the birth of the medium while capturing a world in motion. From the actualités of the Lumière brothers in the late 19th century to the heavily manipulated ethnographic films of the 1920, from the vérité films of the Maysles brothers to the man-on-the-street agitprop popularized by Michael Moore, documentaries have naturally always been more responsive to their times than any other mode of filmmaking.

Not only do they reveal our world to us, but they shape how we view it, and the early years of the 21st century have proven that to be more true than ever before. On one hand, digital technology has infinitely expanded our range of vision, and some of the modern era’s most essential docs have been shot on consumer-grade equipment like iPhones and GoPro cameras. On the other hand, these tools haven’t just granted us new ways of seeing, they’ve also galvanized our desire to look, which in turn has stoked an unprecedented degree of interest in the documentary format on the whole.

Truth has never been so much stranger than fiction than it is today, and the movies show us why. They include personal essays and shocking exposés, touching character studies and sprawling portraits of communal resilience. They feature the cats of Istanbul, the bears of Alaska, and gorillas of the Congo. They document injustices and complex family bonds. Above all, they teach us to see the world around us in new ways. Here are the 50 best documentaries of the 21st century.

With editorial contributions by Christian Blauvelt, Alison Foreman, and Zack Sharf.

[Editor’s note: This list was first published in July 2017 and has been updated multiple times since.]

“Mr. Bachmann and His Class”

Courtesy Everett Collection

Maria Speth proves herself a cinematic heir to Frederick Wiseman with this 217-minute “fly on the wall” depiction of about six months in the classroom of an elementary school for immigrant children in a small German town. 64-year-old Dieter Bachmann is not a perfect teacher, but an exceptionally kind and empathetic one. There are various culture clashes among the children, all hailing from very different backgrounds, and some kinder-crises, but this classroom could practically be a model for a future where our differences are respected and we can all get along together. Watching the film is a kind of Zen experience in hope and tranquility. Not one disconnected from the history of its setting either: Bachmann tells the kids about how their town hosted slave labor during the Third Reich. Through her long takes, Speth creates a deep immersion in the classroom, like you’re part of their conversations too. While it unfolds, you’ll experience something magical: you’ll see the world again as if through the eyes of a child. —CB

Angela Davis in “13th”

Netflix

Ava DuVernay’s documentary “13th” has the precision of a foolproof argument underscored by decades of frustration. The film, which opened the 2016 New York Film Festival, tracks the criminalization of African Americans from the end of the Civil War to the present day, assailing a broken prison system and other examples of institutionalized racial bias with a measured gaze. It combines the rage of Black Lives Matter and the cool intelligence of a focused dissertation.

DuVernay aligns many historical details into an infuriating arrangement of statistics and cogent explanations for the evolution of racial bias in the United States, folding in everything from D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” to the war on drugs. The broad scope is made palatable by the consistency of its focus, and the collective anger it represents.

Visually, the movie offers little more than the standard arrangement of talking heads, archival footage, and animated visual aids, but that’s all it takes to make its incendiary statements resonate across time. The documentary, which followed DuVernay’s feature hits like “Selma” and her early, music-focused documentary works, consolidates some 150 years of American history to show how the country’s current problems with race didn’t happen overnight. It’s required viewing that only grows more essential with each passing day. —EK

“All These Sleepless Nights”

It would be reductive and unfair to say that Michal Marczak’s “All These Sleepless Nights” is the film that Terrence Malick has been trying to make for the last 10 years, but it certainly feels that way while you’re watching it. A mesmeric, free-floating odyssey that wends its way through a hazy year in the molten lives of two Polish twentysomethings, this unclassifiable wonder obscures the divide between fiction and documentary until the distinction is ultimately irrelevant.

Unfolding like a plotless reality show that was shot by Emmanuel Lubezki, this lucid dream of a movie paints an unmoored portrait of a city in the throes of an orgastic reawakening. From the opening images of fireworks exploding over downtown Warsaw, to the stunning final glimpse of Marczak’s main subject — Krzysztof Baginski (playing himself, as everyone does), who looks and moves like a young Baryshnikov — twirling between an endless row of stopped cars during the middle of a massive traffic jam, the film is high on the spirit of liberation. More than just a hypnotically hyper-real distillation of what it means to be young, “All These Sleepless Nights” is a haunted vision of what it means to have been young. —DE

“No Home Movie”

Even before she committed suicide last fall, Chantal Akerman’s final work “No Home Movie” was a tragic statement on the futility of life. An essayistic account of the filmmaker’s relationship to her ailing mother, a Holocaust survivor lost in the fog of faded memories, “No Home Movie” drifts through a somber world with ghostlike intrigue. In between fragments of Skype conversations and living room hangout sessions, Akerman inserts prolonged shots of landscape, sometimes in motion and elsewhere completely still. At one point, she lingers on her murky reflection in a pond. Individually, these moments are difficult to parse; collectively, they amount to an existential wail. At the same time, they carry a profound beauty that hints at more uplifting possibilities.

Of course, “No Home Movie” belongs to a more specific tradition of experimental cinema, both from Akerman’s own oeuvre and many others. But it has a unique rhythm that demands patient viewers and rewards them for their efforts. No matter the depressing undertones, it’s a spectacular parting gift. —EK

“Twenty Feet from Stardom”

Morgan Neville’s Oscar winning documentary “20 Feet From Stardom” hits you like an explosion of joy that’s impossible to shake. What it lacks in narrative innovation it more than makes up for in emotion. Neville spotlights the behind-the-scenes lives of some of the most famous backup singers in music, including Darlene Love, Judith Hill, Merry Clayton, Lisa Fischer and Táta Vega.

Some love supporting other artists and just want to sing, others have dreams to be at the front of the stage. Each woman harbors a self-possessed artistry that is awe-inspiring, and baring witness as they get the spotlight they deserve provides a sensation that makes your heart soar. Try not to stand up and cheer as Mick Jagger listens to Merry Clayton’s stripped vocals on the “Gimme Shelter” chorus. Moments like these are pure bliss for music lovers, and “20 Feet From Stardom” is full of dozens of them. In finding an inspirational topic and telling it with confidence and respect, Neville makes the crowd-pleasing doc of the 21st century. —ZS

“Amy”

Asif Kapadia’s primary skill as a documentarian is his ability to assemble miles upon miles of archival footage into coherent, insightful, and often deeply emotional looks at singular lives. For his much-hyped follow-up to 2010’s exceptional “Senna,” Kapadia turned his eye to one of the modern pop culture’s most exposed — and most misunderstood — stars, using his “Amy” to unpack the tragic rise and fall of singer and songwriter Amy Winehouse.

The British chanteuse’s story had ostensibly been told before, splashed across tabloid pages and gossip blogs, but Kapadia uses his film to find the real person underneath the rumors and lies. What “Amy” does so compellingly is take its audience inside Winehouse’s wild life without judgement or fear, exposing both her flaws and her greatest assets, and showing off her immense talent at every turn. It’s a heartbreaker, because it has to be, because it is, but it’s also a rewarding examination of a life taken too soon, cut too short, and silenced too early. —KE

“Kedi”

The “Citizen Kane” of cat documentaries — take that, “Lil Bub & Friendz” — this sophisticated, artful documentary from Turkish filmmaker Ceyda Torun isolates the profound relationship between man and cat by exploring it across several adorable cases in a city dense with examples. The result is at once hypnotic and charming, a movie with the capacity to elicit both the OMG-level effusiveness of internet memes and existential insights. Torun interviews a variety of locals across Istanbul about their bonds with the creatures, but the cats themselves take center stage, transforming the experience into a spiritual meditation on their significance to modern civilization.

One interviewee argues that the relationship between cats and people is the closest we might get to understanding what it’s like to interact with aliens. If so, “Kedi” goes a long way towards making first contact. Then again, dog people may find themselves in the dark. —EK

“The Central Park Five”

An infuriating look at one of the most offensive, racially-motivated cases in modern history, “The Central Park Five” provides a welcome exception to the usual Ken Burns routine. Part of its distinction comes from the other names associated with the project: Burns co-directed the movie with his daughter Sarah Burns and her husband David McMahon; the subject matter is partly derived from Sarah Burns’ book “The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding.” But there’s still a sense that the proverbial “Ken Burns effect” takes on new meaning — rather than zooming in on old images, Burns magnifies neglected facts to reveal a horrific miscarriage of justice.

The case in point is the scenario that led five Harlem teenagers to spend their young adulthood behind bars for a crime they didn’t commit. These teens were victimized in the wake of “The Central Park Jogger” incident in which a young woman was raped in Central Park; much of the city’s more prominent figures (including Donald Trump) honed in on the racist notion of “wildings,” a reductive term of youth gang activities, to explain the case. The directors gradually pull apart this notion and exonerate their subjects, but even as “Central Park Five” reaches some modicum of a happy ending, the sentiments behind the suffering these men endured in the public light amounts to a stunning modern tragedy. —EK

“After Tiller”

A Kansas physician whose deep belief in reproductive rights led him to become the medical director of Women’s Health Care Service at a time when it was one of the only three clinics in America that was willing to provide late term abortions, George Tiller was repeatedly targeted by right-wing extremists before his eventual assassination in 2009. Per its title, Martha Shane and Lana Wilson’s remarkable “After Tiller” plunges into the politically fraught health crisis that its namesake left behind as it follows the trials and tribulations (and bittersweet mercies) of the four doctors who vowed to continue Tiller’s work in the face of grave danger.

Opting to shine light on the perils of abortion providers — and abortion legislation — instead of turning up the heat on an already combustible situation, Shane and Wilson’s film eschews politics for the people who have to live with them. By empathizing with the extraordinary and heartbreaking circumstances under which a prospective mother would choose to deliver a stillborn fetus, this profoundly empathetic documentary reveals how obfuscating the rhetoric around abortion has become. It is, in its own gentle way, an urgent rallying cry for the preservation of a woman’s right to choose in the face of an unfathomable situation where everything else has already been taken from them. —DE

“Searching for Sugar Man”

Sony Pictures Classics

When 1970s Mexican-American singer-songwriter Sixto Rodriguez faded from view, he’d never had much visibility in the first place. Typically known only as “Rodriguez,” the musician’s gentle pop tunes and activist spirit came through in a handful of albums that were barely noticed in the U.S. However, “Searching for Sugar Man,” documentarian Malik Bendjelloul’s remarkable chronicle of Rodriguez’s neglect on his home turf and unexpected stardom in South Africa, compellingly argues for his place in the canon of great American rock stars, whether or not he wants the spot.

Rodriguez’s music gives the movie a masterful soundtrack and explains its purpose all at once. His lyrics grapple with the plight of the working man, but swap political rhetoric for personal yearning. Bendjelloul tracks his subject’s life through a combination of testimonials from diehard Rodriguez fans and metropolitan landscapes to underscore the music’s evocative power. But it’s the South African context that gives “Searching for Sugar Man” its meatiest hook. For a quarter of a century — unbeknownst to most Americans, including Rodriguez’s original producers — the singer landed a massive following in the country where his humanitarian outlook provided an escape for many disgruntled youth struggling under apartheid, elevating him to the stature of a “South African Elvis.”

The director makes a convincing case for Rodriguez as a phantom rock star, no less valid than Bob Dylan, but never validated by the marketplace. “Rodriguez, as far as I’m concerned, never happened,” a former producer sighs, but the truth is more spectacular: Rodriguez simply made peace with his professional failings, and gained popularity without the aid of the industry. He was a hero who never chased the spotlight. —EK

Non-fiction cinema has been evolving since the birth of the medium while capturing a world in motion. From the actualités of the Lumière brothers in the late 19th century to the heavily manipulated ethnographic films of the 1920, from the vérité films of the Maysles brothers to the man-on-the-street agitprop popularized by Michael Moore, documentaries have naturally always been more responsive to their times than any other mode of filmmaking.

Not only do they reveal our world to us, but they shape how we view it, and the early years of the 21st century have proven that to be more true than ever before. On one hand, digital technology has infinitely expanded our range of vision, and some of the modern era’s most essential docs have been shot on consumer-grade equipment like iPhones and GoPro cameras. On the other hand, these tools haven’t just granted us new ways of seeing, they’ve also galvanized our desire to look, which in turn has stoked an unprecedented degree of interest in the documentary format on the whole.

Truth has never been so much stranger than fiction than it is today, and the movies show us why. They include personal essays and shocking exposés, touching character studies and sprawling portraits of communal resilience. They feature the cats of Istanbul, the bears of Alaska, and gorillas of the Congo. They document injustices and complex family bonds. Above all, they teach us to see the world around us in new ways. Here are the 50 best documentaries of the 21st century.

With editorial contributions by Christian Blauvelt, Alison Foreman, and Zack Sharf.

[Editor’s note: This list was first published in July 2017 and has been updated multiple times since.]

50. “Mr. Bachmann and His Class” (2021)

“Mr. Bachmann and His Class”

Courtesy Everett Collection

Maria Speth proves herself a cinematic heir to Frederick Wiseman with this 217-minute “fly on the wall” depiction of about six months in the classroom of an elementary school for immigrant children in a small German town. 64-year-old Dieter Bachmann is not a perfect teacher, but an exceptionally kind and empathetic one. There are various culture clashes among the children, all hailing from very different backgrounds, and some kinder-crises, but this classroom could practically be a model for a future where our differences are respected and we can all get along together. Watching the film is a kind of Zen experience in hope and tranquility. Not one disconnected from the history of its setting either: Bachmann tells the kids about how their town hosted slave labor during the Third Reich. Through her long takes, Speth creates a deep immersion in the classroom, like you’re part of their conversations too. While it unfolds, you’ll experience something magical: you’ll see the world again as if through the eyes of a child. —CB

49. “13th” (2016)

Angela Davis in “13th”

Netflix

Ava DuVernay’s documentary “13th” has the precision of a foolproof argument underscored by decades of frustration. The film, which opened the 2016 New York Film Festival, tracks the criminalization of African Americans from the end of the Civil War to the present day, assailing a broken prison system and other examples of institutionalized racial bias with a measured gaze. It combines the rage of Black Lives Matter and the cool intelligence of a focused dissertation.

DuVernay aligns many historical details into an infuriating arrangement of statistics and cogent explanations for the evolution of racial bias in the United States, folding in everything from D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” to the war on drugs. The broad scope is made palatable by the consistency of its focus, and the collective anger it represents.

Visually, the movie offers little more than the standard arrangement of talking heads, archival footage, and animated visual aids, but that’s all it takes to make its incendiary statements resonate across time. The documentary, which followed DuVernay’s feature hits like “Selma” and her early, music-focused documentary works, consolidates some 150 years of American history to show how the country’s current problems with race didn’t happen overnight. It’s required viewing that only grows more essential with each passing day. —EK

48. “All These Sleepless Nights” (2016)

“All These Sleepless Nights”

It would be reductive and unfair to say that Michal Marczak’s “All These Sleepless Nights” is the film that Terrence Malick has been trying to make for the last 10 years, but it certainly feels that way while you’re watching it. A mesmeric, free-floating odyssey that wends its way through a hazy year in the molten lives of two Polish twentysomethings, this unclassifiable wonder obscures the divide between fiction and documentary until the distinction is ultimately irrelevant.

Unfolding like a plotless reality show that was shot by Emmanuel Lubezki, this lucid dream of a movie paints an unmoored portrait of a city in the throes of an orgastic reawakening. From the opening images of fireworks exploding over downtown Warsaw, to the stunning final glimpse of Marczak’s main subject — Krzysztof Baginski (playing himself, as everyone does), who looks and moves like a young Baryshnikov — twirling between an endless row of stopped cars during the middle of a massive traffic jam, the film is high on the spirit of liberation. More than just a hypnotically hyper-real distillation of what it means to be young, “All These Sleepless Nights” is a haunted vision of what it means to have been young. —DE

47. “No Home Movie” (2016)

“No Home Movie”

Even before she committed suicide last fall, Chantal Akerman’s final work “No Home Movie” was a tragic statement on the futility of life. An essayistic account of the filmmaker’s relationship to her ailing mother, a Holocaust survivor lost in the fog of faded memories, “No Home Movie” drifts through a somber world with ghostlike intrigue. In between fragments of Skype conversations and living room hangout sessions, Akerman inserts prolonged shots of landscape, sometimes in motion and elsewhere completely still. At one point, she lingers on her murky reflection in a pond. Individually, these moments are difficult to parse; collectively, they amount to an existential wail. At the same time, they carry a profound beauty that hints at more uplifting possibilities.

Of course, “No Home Movie” belongs to a more specific tradition of experimental cinema, both from Akerman’s own oeuvre and many others. But it has a unique rhythm that demands patient viewers and rewards them for their efforts. No matter the depressing undertones, it’s a spectacular parting gift. —EK

46. “Twenty Feet from Stardom” (2013)

“Twenty Feet from Stardom”

Morgan Neville’s Oscar winning documentary “20 Feet From Stardom” hits you like an explosion of joy that’s impossible to shake. What it lacks in narrative innovation it more than makes up for in emotion. Neville spotlights the behind-the-scenes lives of some of the most famous backup singers in music, including Darlene Love, Judith Hill, Merry Clayton, Lisa Fischer and Táta Vega.

Some love supporting other artists and just want to sing, others have dreams to be at the front of the stage. Each woman harbors a self-possessed artistry that is awe-inspiring, and baring witness as they get the spotlight they deserve provides a sensation that makes your heart soar. Try not to stand up and cheer as Mick Jagger listens to Merry Clayton’s stripped vocals on the “Gimme Shelter” chorus. Moments like these are pure bliss for music lovers, and “20 Feet From Stardom” is full of dozens of them. In finding an inspirational topic and telling it with confidence and respect, Neville makes the crowd-pleasing doc of the 21st century. —ZS

45. “Amy” (2015)

“Amy”

Asif Kapadia’s primary skill as a documentarian is his ability to assemble miles upon miles of archival footage into coherent, insightful, and often deeply emotional looks at singular lives. For his much-hyped follow-up to 2010’s exceptional “Senna,” Kapadia turned his eye to one of the modern pop culture’s most exposed — and most misunderstood — stars, using his “Amy” to unpack the tragic rise and fall of singer and songwriter Amy Winehouse.

The British chanteuse’s story had ostensibly been told before, splashed across tabloid pages and gossip blogs, but Kapadia uses his film to find the real person underneath the rumors and lies. What “Amy” does so compellingly is take its audience inside Winehouse’s wild life without judgement or fear, exposing both her flaws and her greatest assets, and showing off her immense talent at every turn. It’s a heartbreaker, because it has to be, because it is, but it’s also a rewarding examination of a life taken too soon, cut too short, and silenced too early. —KE

44. “Kedi” (2016)

“Kedi”

The “Citizen Kane” of cat documentaries — take that, “Lil Bub & Friendz” — this sophisticated, artful documentary from Turkish filmmaker Ceyda Torun isolates the profound relationship between man and cat by exploring it across several adorable cases in a city dense with examples. The result is at once hypnotic and charming, a movie with the capacity to elicit both the OMG-level effusiveness of internet memes and existential insights. Torun interviews a variety of locals across Istanbul about their bonds with the creatures, but the cats themselves take center stage, transforming the experience into a spiritual meditation on their significance to modern civilization.

One interviewee argues that the relationship between cats and people is the closest we might get to understanding what it’s like to interact with aliens. If so, “Kedi” goes a long way towards making first contact. Then again, dog people may find themselves in the dark. —EK

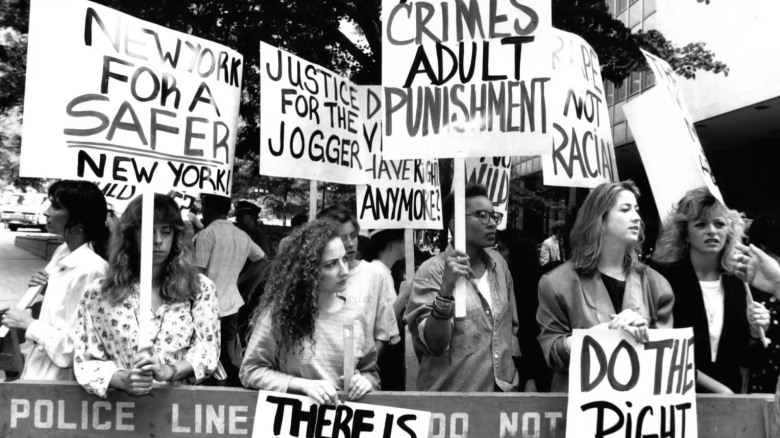

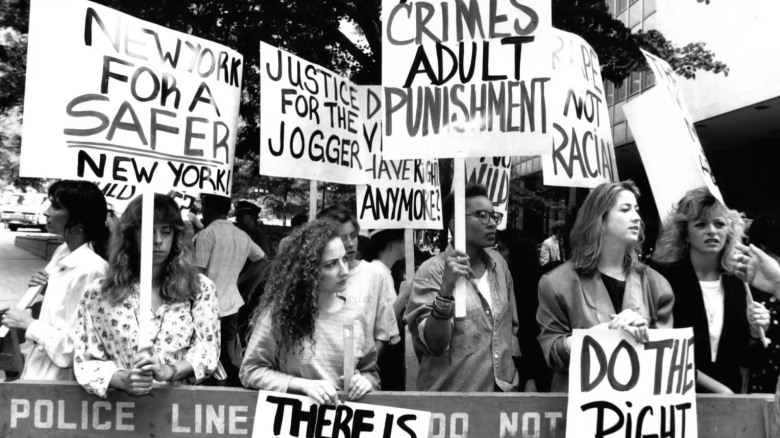

43. “The Central Park Five” (2012)

“The Central Park Five”

An infuriating look at one of the most offensive, racially-motivated cases in modern history, “The Central Park Five” provides a welcome exception to the usual Ken Burns routine. Part of its distinction comes from the other names associated with the project: Burns co-directed the movie with his daughter Sarah Burns and her husband David McMahon; the subject matter is partly derived from Sarah Burns’ book “The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding.” But there’s still a sense that the proverbial “Ken Burns effect” takes on new meaning — rather than zooming in on old images, Burns magnifies neglected facts to reveal a horrific miscarriage of justice.

The case in point is the scenario that led five Harlem teenagers to spend their young adulthood behind bars for a crime they didn’t commit. These teens were victimized in the wake of “The Central Park Jogger” incident in which a young woman was raped in Central Park; much of the city’s more prominent figures (including Donald Trump) honed in on the racist notion of “wildings,” a reductive term of youth gang activities, to explain the case. The directors gradually pull apart this notion and exonerate their subjects, but even as “Central Park Five” reaches some modicum of a happy ending, the sentiments behind the suffering these men endured in the public light amounts to a stunning modern tragedy. —EK

42. “After Tiller” (2013)

“After Tiller”

A Kansas physician whose deep belief in reproductive rights led him to become the medical director of Women’s Health Care Service at a time when it was one of the only three clinics in America that was willing to provide late term abortions, George Tiller was repeatedly targeted by right-wing extremists before his eventual assassination in 2009. Per its title, Martha Shane and Lana Wilson’s remarkable “After Tiller” plunges into the politically fraught health crisis that its namesake left behind as it follows the trials and tribulations (and bittersweet mercies) of the four doctors who vowed to continue Tiller’s work in the face of grave danger.

Opting to shine light on the perils of abortion providers — and abortion legislation — instead of turning up the heat on an already combustible situation, Shane and Wilson’s film eschews politics for the people who have to live with them. By empathizing with the extraordinary and heartbreaking circumstances under which a prospective mother would choose to deliver a stillborn fetus, this profoundly empathetic documentary reveals how obfuscating the rhetoric around abortion has become. It is, in its own gentle way, an urgent rallying cry for the preservation of a woman’s right to choose in the face of an unfathomable situation where everything else has already been taken from them. —DE

41. “Searching for Sugar Man” (2012)

“Searching for Sugar Man”

Sony Pictures Classics

When 1970s Mexican-American singer-songwriter Sixto Rodriguez faded from view, he’d never had much visibility in the first place. Typically known only as “Rodriguez,” the musician’s gentle pop tunes and activist spirit came through in a handful of albums that were barely noticed in the U.S. However, “Searching for Sugar Man,” documentarian Malik Bendjelloul’s remarkable chronicle of Rodriguez’s neglect on his home turf and unexpected stardom in South Africa, compellingly argues for his place in the canon of great American rock stars, whether or not he wants the spot.

Rodriguez’s music gives the movie a masterful soundtrack and explains its purpose all at once. His lyrics grapple with the plight of the working man, but swap political rhetoric for personal yearning. Bendjelloul tracks his subject’s life through a combination of testimonials from diehard Rodriguez fans and metropolitan landscapes to underscore the music’s evocative power. But it’s the South African context that gives “Searching for Sugar Man” its meatiest hook. For a quarter of a century — unbeknownst to most Americans, including Rodriguez’s original producers — the singer landed a massive following in the country where his humanitarian outlook provided an escape for many disgruntled youth struggling under apartheid, elevating him to the stature of a “South African Elvis.”

The director makes a convincing case for Rodriguez as a phantom rock star, no less valid than Bob Dylan, but never validated by the marketplace. “Rodriguez, as far as I’m concerned, never happened,” a former producer sighs, but the truth is more spectacular: Rodriguez simply made peace with his professional failings, and gained popularity without the aid of the industry. He was a hero who never chased the spotlight. —EK