The audience cheered and stomped throughout a sold-out screening of “Top Gun: Maverick” at this year’s EnergaCamerimage, an annual festival in Poland dedicated to celebrating the art of cinematography. After the screening everyone at the festival wanted to know how cinematographer Claudio Miranda, who was in attendance, shot the aerial sequences. In an interview with IndieWire, the legendary cameraman was clear: Nothing was simple shooting “Top Gun: Maverick” — not the fighter jets, the aircraft carriers, not even an opening bar sequence that introduces the characters.

Although the dogfights were prevised [Previsualisation], Miranda revealed that a lot of the previs was discarded. “We spent a lot of money on it,” Miranda said, “but we mostly ended up on Tom [Cruise] and the other pilots playing with the steering sticks. It was like they were kids again.”

The only way director Joe Kosinski could sell Cruise on a “Top Gun” sequel some 30-plus years after the original was if they shot in real jets. Miranda worked first with an L 39 Czech jet, then with an older version of an F 18 fighter.

“It’s an older style jet that didn’t have as much electronics,” Miranda explained. “Since my Navy technical guys had all seen the original ‘Top Gun,’ they got behind the idea of pulling out a lot of gear. We ended up fitting six cameras in the cockpit, including one that had about two-and-a-half inches clearance.”

Miranda still couldn’t get all the angles he wanted. The Navy wouldn’t allow cameras on the wings because they would affect performance. “I got a dorsal mount as a consolation prize and the normal bomb mounts,” he added. “But you could only fly the plane at 3Gs with external mounts.”

The jets’ velocity became a huge factor. Jeffrey L. Kimball, the original “Top Gun” cinematographer, reminded him that at 7Gs, a 10-pound camera feels like 70 pounds.

“I thought the original was anamorphic, but they shot spherical because of the camera size and weight,” Miranda said. “Also they were shooting 400-foot rolls, which is about four minutes. We could be smaller on digital. We could shoot for a half-hour with six cameras running. That was a big, big difference.”

Kimball also had advice about lens choices and about working on an aircraft carrier. Before the main production, Miranda and a skeleton crew joined the USS Abraham Lincoln on a training mission. There he was allowed to shoot take-offs, landings, the flight deck, and other details that would end up in the movie.

“Kimball had issues where he couldn’t turn his carrier around,” Miranda said. “I found the right people to talk to, and they would just spin the boat around for me. It doesn’t cost them anything. To be super clear, we were shooting around their missions — they weren’t launching jets for us. And I couldn’t aim towards the sun. But we could turn it this way or that way to get our shots.”

The production was heavily weather dependent. Miranda said the weather cooperated for the most part, although he needed three days to capture the heroic shot of Cruise on a motorcycle racing down a runway as a jet takes off. “Too overcast,” he said of the first efforts. “We got one in the can, but we decided to go back. It had to be at a certain time of day so the jet crosses right through the sun.”

For the flight sequences, Miranda needed to set camera exposures before takeoff. “I had to guess what the weather was 50 miles down the road,” he said. He checked weather reports constantly. “I would look to the east where they were flying and see some clouds and maybe open up a third. Then wait, hold on, they’re going away. Or are the jets going 50 feet down into a canyon? Then go with this exposure. I have to say, I didn’t miss.”

The cinematographer made a point of bringing up “Paths of Hate,” a 2010 animated short written and directed by Damian Nenow.

“We looked at aerial footage in movies, but it didn’t really apply to what we were doing,” he said. “You know, for a racing film you can look at Grand Prix or something to see how they did it, what you want to emulate. We found this animated movie, and in animation they can do anything they want. I showed it to Tom and Joe and said, ‘This would be pretty cool for the sequence flying over water. Why don’t we approach this differently? Why don’t we show things you can’t get anywhere else?'”

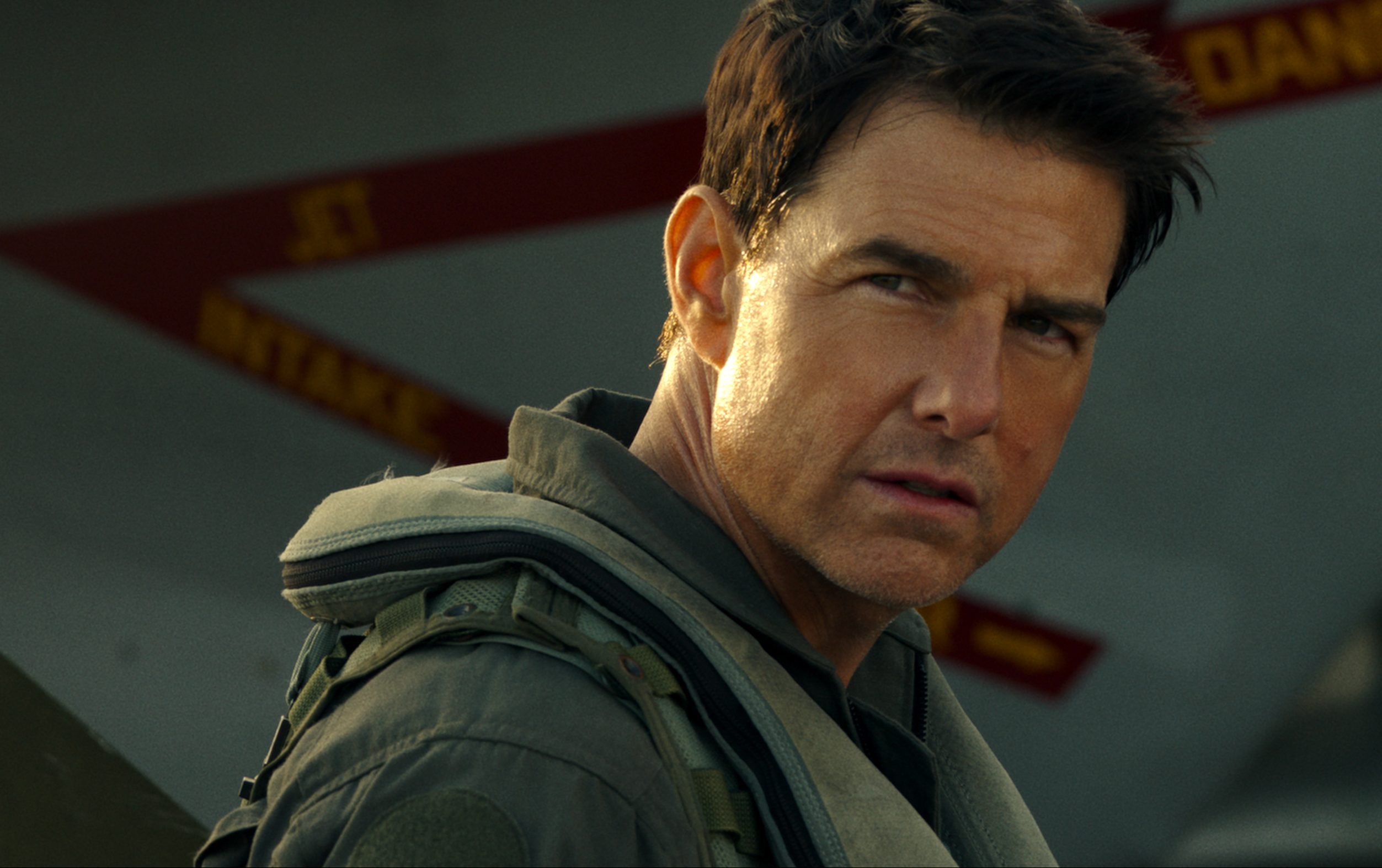

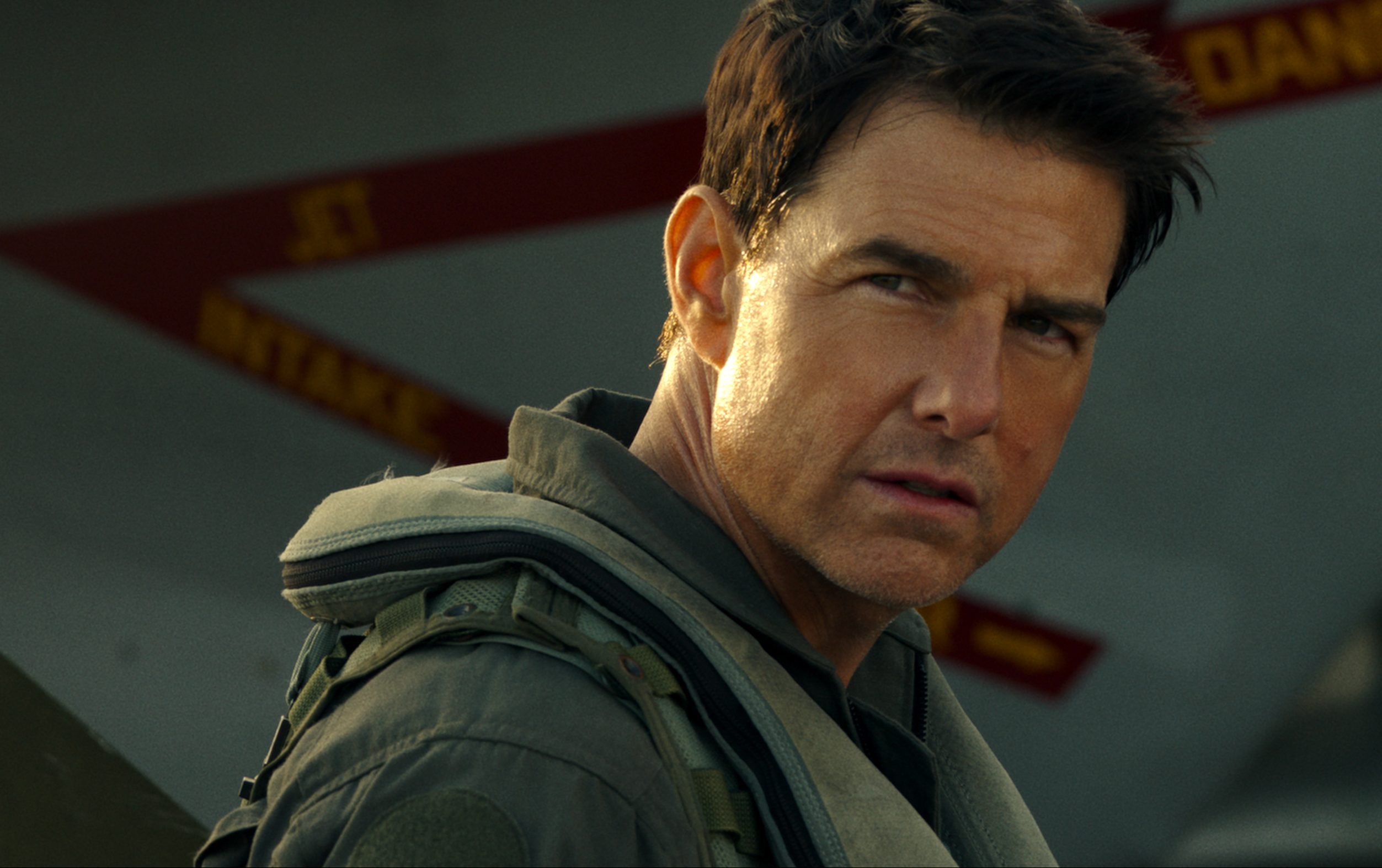

Tom Cruise plays Capt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell in “Top Gun: Maverick”

Paramount Pictures

To capture the movie’s monumental closeups, the cinematographer looked at how older Hollywood movies depicted power. “Stature, how to make people feel strong and powerful. We were always framing and moving cameras in a certain way to make the closeups feel strong. Interestingly enough, Joe and I usually tend to be a little bit wider on lenses. But Tony Scott [director of the original “Top Gun”] was always a little bit longer, so we favored long lenses a little bit more as well.”

Miranda also mentioned different tools at his disposal, like depth of field, or the distance from lens to actor, and how some actors look better on a 65mm vs. 75mm lens, or visa versa. “But sometimes it’s just a moment where it’s you and the actors in a very small scene. Then it’s a question of choosing the right gear. Sometimes it feels nicer to be on a smaller piece of gear without all the other stuff. It can be liberating to have everything you could ever want. But it’s also about making wise choices. You don’t always have to have a Technocrane.”

Miranda said the material determines the visual style of his movies. “My camera movements are rarely Steadicam, rarely handheld. I use a lot of dolly and intentional framing positions, maybe because I was beaten by Fincher [Miranda shot Fincher’s “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”] so much. Everything had to be exact, ‘Split that cup right in half’ or all hell would break loose. So I’m very used to that style. I get it, like you’re coming in on the actor and the dolly movement finishes right on a line and there’s deflating and inflating of movement you could do.”

Miranda would use two cameras for some moments. “I like two cameras,” he said. “Sometimes we had to do three cameras for an emotional scene or to try to clear someone up. But it’s hard for me to really watch two cameras. The third one, it’s like, ‘I hope you’re getting something good,’ because I’m watching the other two. I always feel like the third will be getting hands twiddling.”

That still doesn’t account for the clarity on Miranda’s images, how quickly viewers can comprehend what is essential in a frame. “We try to make it as grounded as possible,” he answered. “We don’t want anything to feel synthetic. Even in regular performances between actors, you can’t allow it to feel false.”

Both Kosinski and Miranda said the flight scenes weren’t the hardest to shoot. They decided to shoot that opening scene in Penny’s (Jennifer Connelly) bar a second time in order to alter the way viewers perceived her relationship with Maverick. Miranda embraced the opportunity to relight the scene.

“Top Gun: Maverick” director Joseph Kosinski and cinematographer Claudio Miranda

Scott Garfield

“Joe wanted a little bit more history between Penny and Maverick,” Miranda explained. “I wasn’t happy about my lighting on the first one. Instead of a bar packed with extras, for the second we could take people away. That let me use a little more side light and move it differently.”

A sequence where Penny takes Maverick sailing proved even more difficult. They couldn’t find enough wind at San Diego or San Pedro.

“I was just sitting on the boat rocking with Tom,” Miranda laughed. “The third time in San Francisco was great. I had one camera on the side of the boat in the front, I operated another camera on the boat next to them, and we had a helicopter as well.”

The scene took some interesting turns.

“I was operating, and Joe was hanging onto the seat. It was a pretty massive day. We blew a spinnaker. We flooded the Libra head. We had the camera department running out panicking.”

Miranda is prepping his next project, a drama about Formula One directed by Kosinski and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and racing legend Lewis Hamilton. It will be another massive film.

“There is scope to it,” Miranda admitted. “Sometimes you have 25 camera teams and it’s all about Technocranes and crazy equipment. But on my last movie, a small piece called ‘Nyad’ [directed by Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi], I was on a boat with just a handheld camera. It was actually kind of freeing to be able to point the boat and just shoot.”

Although the dogfights were prevised [Previsualisation], Miranda revealed that a lot of the previs was discarded. “We spent a lot of money on it,” Miranda said, “but we mostly ended up on Tom [Cruise] and the other pilots playing with the steering sticks. It was like they were kids again.”

The only way director Joe Kosinski could sell Cruise on a “Top Gun” sequel some 30-plus years after the original was if they shot in real jets. Miranda worked first with an L 39 Czech jet, then with an older version of an F 18 fighter.

“It’s an older style jet that didn’t have as much electronics,” Miranda explained. “Since my Navy technical guys had all seen the original ‘Top Gun,’ they got behind the idea of pulling out a lot of gear. We ended up fitting six cameras in the cockpit, including one that had about two-and-a-half inches clearance.”

Miranda still couldn’t get all the angles he wanted. The Navy wouldn’t allow cameras on the wings because they would affect performance. “I got a dorsal mount as a consolation prize and the normal bomb mounts,” he added. “But you could only fly the plane at 3Gs with external mounts.”

The jets’ velocity became a huge factor. Jeffrey L. Kimball, the original “Top Gun” cinematographer, reminded him that at 7Gs, a 10-pound camera feels like 70 pounds.

“I thought the original was anamorphic, but they shot spherical because of the camera size and weight,” Miranda said. “Also they were shooting 400-foot rolls, which is about four minutes. We could be smaller on digital. We could shoot for a half-hour with six cameras running. That was a big, big difference.”

Kimball also had advice about lens choices and about working on an aircraft carrier. Before the main production, Miranda and a skeleton crew joined the USS Abraham Lincoln on a training mission. There he was allowed to shoot take-offs, landings, the flight deck, and other details that would end up in the movie.

“Kimball had issues where he couldn’t turn his carrier around,” Miranda said. “I found the right people to talk to, and they would just spin the boat around for me. It doesn’t cost them anything. To be super clear, we were shooting around their missions — they weren’t launching jets for us. And I couldn’t aim towards the sun. But we could turn it this way or that way to get our shots.”

The production was heavily weather dependent. Miranda said the weather cooperated for the most part, although he needed three days to capture the heroic shot of Cruise on a motorcycle racing down a runway as a jet takes off. “Too overcast,” he said of the first efforts. “We got one in the can, but we decided to go back. It had to be at a certain time of day so the jet crosses right through the sun.”

For the flight sequences, Miranda needed to set camera exposures before takeoff. “I had to guess what the weather was 50 miles down the road,” he said. He checked weather reports constantly. “I would look to the east where they were flying and see some clouds and maybe open up a third. Then wait, hold on, they’re going away. Or are the jets going 50 feet down into a canyon? Then go with this exposure. I have to say, I didn’t miss.”

The cinematographer made a point of bringing up “Paths of Hate,” a 2010 animated short written and directed by Damian Nenow.

“We looked at aerial footage in movies, but it didn’t really apply to what we were doing,” he said. “You know, for a racing film you can look at Grand Prix or something to see how they did it, what you want to emulate. We found this animated movie, and in animation they can do anything they want. I showed it to Tom and Joe and said, ‘This would be pretty cool for the sequence flying over water. Why don’t we approach this differently? Why don’t we show things you can’t get anywhere else?'”

Tom Cruise plays Capt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell in “Top Gun: Maverick”

Paramount Pictures

To capture the movie’s monumental closeups, the cinematographer looked at how older Hollywood movies depicted power. “Stature, how to make people feel strong and powerful. We were always framing and moving cameras in a certain way to make the closeups feel strong. Interestingly enough, Joe and I usually tend to be a little bit wider on lenses. But Tony Scott [director of the original “Top Gun”] was always a little bit longer, so we favored long lenses a little bit more as well.”

Miranda also mentioned different tools at his disposal, like depth of field, or the distance from lens to actor, and how some actors look better on a 65mm vs. 75mm lens, or visa versa. “But sometimes it’s just a moment where it’s you and the actors in a very small scene. Then it’s a question of choosing the right gear. Sometimes it feels nicer to be on a smaller piece of gear without all the other stuff. It can be liberating to have everything you could ever want. But it’s also about making wise choices. You don’t always have to have a Technocrane.”

Miranda said the material determines the visual style of his movies. “My camera movements are rarely Steadicam, rarely handheld. I use a lot of dolly and intentional framing positions, maybe because I was beaten by Fincher [Miranda shot Fincher’s “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”] so much. Everything had to be exact, ‘Split that cup right in half’ or all hell would break loose. So I’m very used to that style. I get it, like you’re coming in on the actor and the dolly movement finishes right on a line and there’s deflating and inflating of movement you could do.”

Miranda would use two cameras for some moments. “I like two cameras,” he said. “Sometimes we had to do three cameras for an emotional scene or to try to clear someone up. But it’s hard for me to really watch two cameras. The third one, it’s like, ‘I hope you’re getting something good,’ because I’m watching the other two. I always feel like the third will be getting hands twiddling.”

That still doesn’t account for the clarity on Miranda’s images, how quickly viewers can comprehend what is essential in a frame. “We try to make it as grounded as possible,” he answered. “We don’t want anything to feel synthetic. Even in regular performances between actors, you can’t allow it to feel false.”

Both Kosinski and Miranda said the flight scenes weren’t the hardest to shoot. They decided to shoot that opening scene in Penny’s (Jennifer Connelly) bar a second time in order to alter the way viewers perceived her relationship with Maverick. Miranda embraced the opportunity to relight the scene.

“Top Gun: Maverick” director Joseph Kosinski and cinematographer Claudio Miranda

Scott Garfield

“Joe wanted a little bit more history between Penny and Maverick,” Miranda explained. “I wasn’t happy about my lighting on the first one. Instead of a bar packed with extras, for the second we could take people away. That let me use a little more side light and move it differently.”

A sequence where Penny takes Maverick sailing proved even more difficult. They couldn’t find enough wind at San Diego or San Pedro.

“I was just sitting on the boat rocking with Tom,” Miranda laughed. “The third time in San Francisco was great. I had one camera on the side of the boat in the front, I operated another camera on the boat next to them, and we had a helicopter as well.”

The scene took some interesting turns.

“I was operating, and Joe was hanging onto the seat. It was a pretty massive day. We blew a spinnaker. We flooded the Libra head. We had the camera department running out panicking.”

Miranda is prepping his next project, a drama about Formula One directed by Kosinski and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and racing legend Lewis Hamilton. It will be another massive film.

“There is scope to it,” Miranda admitted. “Sometimes you have 25 camera teams and it’s all about Technocranes and crazy equipment. But on my last movie, a small piece called ‘Nyad’ [directed by Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi], I was on a boat with just a handheld camera. It was actually kind of freeing to be able to point the boat and just shoot.”