Netflix and Sony’s “The Mitchells vs. the Machines” isn’t the only animated Oscar contender for next year with a wild 2D aesthetic. “Luca” (streaming on Disney+ June 1

also sports a 2D look that’s unique for Pixar. Director Enrico Casarosa — who first experimented with watercolors and pastels to make graphic shapes and waves on his Oscar-nominated short, “La Luna” — achieves a more daring, painterly approach for his feature debut.

also sports a 2D look that’s unique for Pixar. Director Enrico Casarosa — who first experimented with watercolors and pastels to make graphic shapes and waves on his Oscar-nominated short, “La Luna” — achieves a more daring, painterly approach for his feature debut.It’s about a bromance between two sea monsters, the 13-year-old protagonist of the title (voiced by “Wonder” star Jacob Tremblay) and his new friend, Alberto (voiced by “Shazam’s” Jack Dylan Grazer), who can turn human above the sea on the Italian Riviera. They share an enchanting summer riding Vespa scooters, eating pasta and Gelato, and diving off the rugged cliffs into the turquoise water, while soaking up the beauty of the pastel seaside town. But at the same time, they try to hide their secret identities in a story which debunks the myth that sea monsters are horrible creatures.

“The other side of being a kid is that you always feel like you’re the outsider,” said Casarosa, who drew on his own childhood on the Italian Riviera. “Me and my friend felt like such losers when we would hang out. And I love how the sea monster is a wonderful metaphor for feeling different. And I loved the drawings of these old [sea] creatures in the maps,” added the storyboard artist-turned director.

“Luca”

Disney/Pixar

Aesthetically, Casarosa expanded on the 2D look of “La Luna” with a vibrant depiction of the coastal fishing village that resembles an illustrated book. And the characters are reminiscent of stop-motion. “We tried to bring some warmth to the computer animation,” he continued, “so we really worked hard to make it more stylized and bring textures that are handmade.” The slow, extended leap into the sea offers the kind of hard poses associated with 2D cartoons. He said it was “like jumping into a kid’s book.”

“We talked a lot about limited animation, and I showed [the Pixar artists] one of the cartoons that I grew up with: Miyazaki’s ‘Future Boy Conan,’ [the sci-fi anime series from ’78],” added Casarosa. “It has snappy poses that show the playfulness of youth.” And the quirkiness of “Luca” was encouraged by director/chief creative officer Pete Docter (“Soul”), who advised him not to soften the edges, and to keep it weird. However, early on, the look ranged from overly stylized to overly simplified, and Docter advised them to be more polished.

But, like Mike Rianda, director of “The Mitchells vs. the Machines,” Casarosa was also keen on incorporating drawings and concept art directly into the animation. Pixar had the software to pull it off, but “Luca” took them out of their comfort zone with the most 2D-looking feature they’ve made to date. They could bring painterly textures to the characters, sets, and water, add strange shapes to the clouds, and push the colors while reducing distracting details when necessary. Yet a fantasy Vespa-riding sequence to the moon with flying lunar fish hit just the right surrealistic vibe.

“Luca”

Disney/Pixar

Meanwhile, Casarosa, who likes to add rouge to cheeks, elbows, and knees to his drawings, had to wait patiently for the tech team to pull it off with CG animation. “In 2D, you would put that perfect shape wherever, regardless of how big the mouth is,” said character supervisor Beth Albright. “But in 3D, if you painted the model and shaded that in, as the mouth shape is changing, the area of that blush is going to turn into something weird. So instead we pulled it off of the skin, and created a little hand-painted area, and the animators could actually pose it where they wanted.”

For the skin, they applied warm and soft surfacing and layered on top more detail in some places and less detail in others. The trick was getting the faces to move realistically. They also added hand-painted textures to the eyes for a more stylized, less physically-based appearance. The rigging of Luca and Alberto was new as well, allowing them to utilize more squash-and-stretch with customized controls for the mouth, silhouettes, and profiles. “We introduced new kinds of controls for their trumpet-shaped mouths, which moved from small shapes to big shapes,” added character supervisor Sajan Skaria.

Going into a profile without breaking the silhouette, though, was a formidable challenge. In their normal character rig, the mouth locks onto the head whenever you turn it and it moves dimensionally. “Here we broke that loose so you could turn the head and keep the mouth inside the silhouette and swing it and pop quickly into profile,” said animation supervisor Mike Venturini. “That’s really hard to do in CG with a tangible model that’s rigid in form.”

“Luca” Multi-Limbs

Disney/Pixar

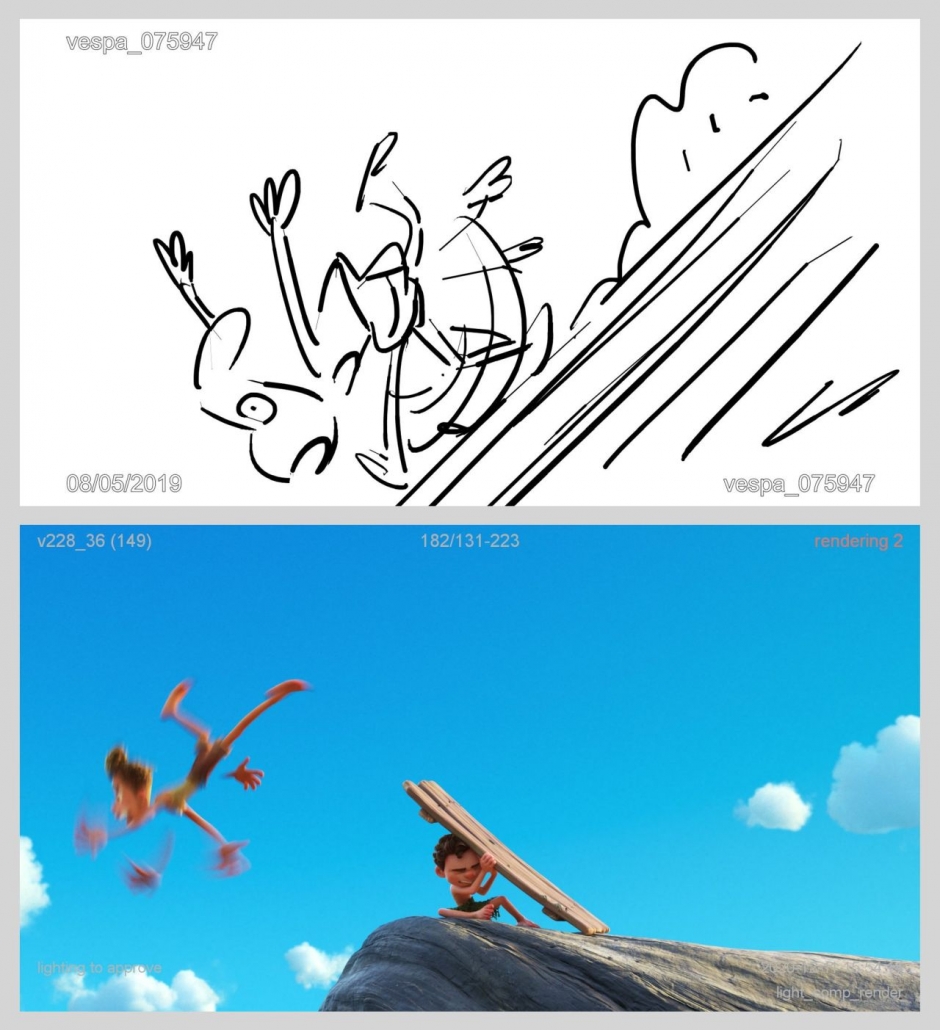

But the most effective technique borrowed from cartoons was the adoption of multi-limb movement during fast action. This came half-way into production when Casarosa wanted to directly translate the look of his drawings. “Someone pointed out to me that the sequence I boarded was so goofy, I just wanted to include that fast noodling as an homage to Miyazaki’s ‘The Castle of Cagliostro,'” Casarosa said. But we realized we wanted it to be more like ‘Looney Tunes’ with much more cartoony multiple hands and legs.”

When they first tried it, though, by loading a second character, the extra legs abruptly cut off at the ankles or knees or connected awkwardly. But then Venturini realized they could re-purpose the special rig they made for the sea monster/human transformations using a variation on the blending. “What if we just blended from human to nothing?” he said. “Then we put that rig in on the character and tried doing it, and it allowed us to fade those limbs out and choose where you wanted them to fade back in on the leg or the arm. Then we suddenly had versatility on each individual frame to choose how much of that extra limb to show. And when you added a little bit of motion blur, it started to look exciting. We would share what we were developing with Pete Docter to see if he was cool with putting this on the big screen and he really had fun with this.” [Unfortunately, Disney has chosen to bypass a theatrical release.]

“It was about finding the shapes and modifying them,” Casarosa said. “Finding the essence of something and taking things out. We kept saying, ‘When is less more? And how do we make it immersive and rich?’ So there was an interesting journey because we didn’t know what it would look like in the beginning.”