It was 48 hours before the Oscar ceremony and Darius Marder was walking around Los Angeles. “This is one of the few times I’m just wandering around, getting the hell out,” he said.

The “Sound of Metal” writer and director, who was up for two awards and would win neither, had spent the last few days in a last-minute campaign sprint for his drama about a deaf addict while jugging a few commercial shoots. Talking on the phone while he wandered the streets, Marder spoke breathlessly about the psychological effect of getting an 11-year passion project made, only to reiterate that story in the endless zooming of a pandemic awards season.

“You spent a lot of time thinking about this final frontier of recognition, this peer acknowledgement. But here’s what I know,” he said. “What I know is that this film is what it is because I could give a flying fuck about these awards. I was never making the film for that reason. It has never been about pandering or playing any game other than serving the movie in its truest form.”

That was the overarching sentiment of a weird Oscar weekend when everything felt so constrained that it was a wonder the awards themselves weren’t adorned in tiny masks. Following the proceedings from New York, I called and texted with nominees as the ceremony drew near. Many said they expected to lose — and did. There was more interest in discussing self-preservation than regarding the glow of a socially distant red carpet. With the state of exhibition uncertain as COVID-19 continued to rage worldwide, I heard more battle cries about keeping the art form alive than pleas to keep the business intact.

Some took in the mythological dimensions. Danish auteur Thomas Vinterberg, whose Best International Feature win for “Another Round” would be an early emotional highlight of the show, told me he and his wife spent a week of quarantine high in the Hollywood Hills, homeschooling their kids and watching “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” after they went to a bed “with a whiskey sour in our hands.” He marveled at Charlie Chaplin’s old house nearby. “I am imagining what must have happened there,” he said.

Others already planned next steps. “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” breakout Maria Bakalova was an unknown Bulgarian actress less than a year ago; now the 24-year-old juggled final Oscar duties with plans to launch a production company with fellow Bulgarian Julian Kostov to support more Eastern Europeans in the film industry. “I want to advocate for equal representation as well as the normalization of foreign accents on screen and shedding negative stereotypes,” she said. “Diversity is crucial to our industry.”

That mentality, crucial to the Oscar-season narrative in recent years yet often reduced to soundbites, hovered uncomfortably at the center of a surreal ceremony. Staged like a movie (and at times, it looked as visually dynamic), familiar dramas brought it down to Earth. Black actors were shut out of top performance categories, right down to the stinging finale. With most nominees unfamiliar to mainstream audiences, the show gave the unfortunate impression of an industry struggling to maintain its relevance. The letterboxed aspect ratio opened up the frame, but everyone looked constrained: a hip crowd, shunted into the corner of popular culture.

For many nominees whose work already falls outside of the system, that outcome is business as usual. A sense of smallness, with its preordained bad ratings and pathetic box office, felt not unlike the marginalization experienced by many filmmakers on the regular even when they muster a modicum of professional recognition.

Chloé Zhao on Oscar night

“Nomadland” director Chloé Zhao touched on that sentiment hours before her historic pair of Oscar wins, for Best Director and Best Picture, while talking to a red carpet interviewer before the show. She spent three months making her Best Picture winner on the road and in secret, with mostly non-professional actors on a $5 million budget. “Sometimes,” she said, “filmmaking can be a quite lonely, and transient, experience.”

The triumph of that gutsy, experimental swing, one year after “Parasite” dominated the Oscars, illustrated the divide between uniform crowdpleasers that drive studios’ quarterly reports and the individualism that compels the strongest directors to stay in the game.

“To me, this year’s Oscars reflect an intuitive state of where cinema is going,” said “Nomadland” producer Dan Janvey the day before his Best Picture win. “Whether or not Hollywood is OK with that — or even realizes that — it’s tremendously exciting to me. These are just thrilling movies.”

Janvey, a veteran of the filmmaking collective Court 13, last made the awards-season rounds as a nominee behind Benh Zeitlin’s “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” a film that taught him about the practical challenges of shooting on the fly in real places. “The last time we did this, I don’t think we were actively trying to win anything,” he said. “There was just a gleefulness about being in some of those rooms.” (Janvey also co-produced Best Documentary nominee “Time,” a black-and-white repudiation of the criminal justice system that deserved to win.)

“We try to generalize the Oscars into a state of cinema,” Janvey said. “The truth is that cinema has a lot of different moments where that happens for different bodies of people. Cannes, to me, is Rosh Hashanah. Maybe the Oscars are Passover. The point is, if you want to look at the Oscars as a state of where the industry and people who make movies, I think overall this year’s nominees are historically incredible.”

More than that, he added: “If your orientation is more toward global cinema than just the studio cinema, there’s something exciting about where the Oscars are pushing the conversations. I think of Chloé in that context.”

“Nomadland”

Searchlight

Like many nominees, Janvey felt hampered by the virtual nature of the campaign process. “You don’t get that sense of talking to the other filmmakers about their work, and it’s really sad,” he said. “That’s one of the more special moments of being in a film community — that kind of sharing of work.”

Looking ahead to the show, Janvey was keen to connect with Sergio Chamy, the 83-year-old subject of Chilean Best Documentary nominee “The Mole Agent,” who infiltrated a nursing home in the movie; his Oscar attendance marked his first trip to America. “The number-one person I want to meet and take a picture with is Sergio,” he said. “So much attention is given to the horse race component and there’s actually another really, really beautiful aspect of it that gets less attention.”

Later, I connected Janvey with “The Mole Agent” director Maite Alberdi on a WhatsApp chain and they began to swap enthusiasm for each other’s work while plotting the photo opp at Union Station. Alberdi said the trip to L.A. was a particularly disorienting experience as her native Santiago remains in lockdown.

“We did not believe we could be here,” she told me on Saturday. Without the budgetary resources to mount an aggressive campaign, Alberdi and her team built an online DIY effort that actually benefited from the unorthodox year. “If I had to spend a million dollars on a campaign and invite everyone to cocktails and put up big posters in every city, I’d never do it,” she said. “This film was financed mostly from public television. It’s impossible to create a traditional Oscar campaign with that.”

Over the past year, she juggled everyday life with endless promotional duties. “I could go pick up my son at kindergarten every day in Chile and still run my Oscar campaign. That was unbelievable,” she said. “I think the pandemic definitely impacted the relationship that we have with the audience in theater, but on the other hand, I think I did more Q&As in different parts of the world because I couldn’t travel. I thought the film was going to be lost in the sea of films during the pandemic. Instead, it was more visible.” The movie landed on the Best International Film and Best Documentary shortlists; it was the first Chilean documentary to be nominated.

Alberdi said the ongoing pandemic meant she can’t resume her intimate approach to non-fiction, which turns on eccentric characters like Chamy. “This is the first time in 11 years that I haven’t shot a new film for a whole year,” she said, recalling how she had to pause production when shutdowns took hold. “I cannot apply COVID protocols to continue shooting vulnerable characters who I cannot put at risk. I don’t know when I’ll use the camera again, and that is really frustrating.”

A few thousand miles away in the United Kingdom, Field of Vision cofounder and Best Documentary Short nominee Charlotte Cook watched the show with her parents under quarantine. When her father booked an embolism-related surgery days before the broadcast, she decided to stay home. Given the late hour of the program, her mother bought fancy pajamas for the experience. “It’s a strange experience,” said Cook, who produced “Do Not Split,” “but family comes first.”

Nominations for “Do Not Split,” which details the recent Hong Kong protests against the oppressive Chinese government, resulted in the broadcast being banned in China. “The day after my nomination, I spent hours on the phone with lawyers,” Cook said. “We imagined there would be some kind of response, but not on that level.” Working with the film’s Norwegian director, Anders Hammer, Cook used the fleeting attention of the Oscar nomination to raise awareness of the ongoing dangers faced by Hong Kong citizens who push back on Mainland censorship. “We are both privileged people, being white and European and having safety in this moment to speak about this issue,” she said. “We’ve had to balance what our film is about and what we’re trying to talk with this odd experience of being celebrated. This is not something that’s in the past. It’s happening now.”

Just last week, she added, another documentary producer in Hong Kong was convicted by the Chinese government. “This is something we have to talk about,” she said. For her, the Zoom-based campaigning process limited social opportunities but it also enabled international stories to travel. “That’s a barrier that’s been broken,” she said.

Catalin Tolontan in “Collective”

A beneficiary of that shift was Alexander Nanau, the Romanian director whose “Collective” landed nominations for both Best Documentary and Best International Film. A bracing real-time thriller as its journalist subjects unearth a healthcare scandal at the highest levels of the Romanian government, the movie documents a failing democracy and the passionate efforts to decry its collapse. “I continue to feel thankful for all that the Oscar nominations have done for our film around the world,” Nanau told me. “The surprise of the campaign was to see that even though we had so many restrictions from the pandemic, movies can travel.”

For the 2021 Oscars, travel became a synonym for thousands of Zoom panels Marder guessed that he participated in upward of 300 promotional Zooms to support “Sound of Metal,” and that was a conservative estimate.

“Zooms are inherently exhausting,” he said. “They just require attention and there’s just an awkwardness to them. You just feel like you’re putting out energy all the time.” At the same time, he treasured the recurring opportunities to see his “Sound of Metal” collaborators, even in little digital boxes at the mercy of tenuous wifi connections. “We all found each other texting afterwards,” he said. “In isolation, these Zooms turned into a lifeline for us.”

During the show, Marder celebrated as “Sound of Metal” scored Best Editing and Best Sound. “I had to engage in a process of educating people about the relationship between editing and sound in this film,” he beamed. “I saw that take root.” Looking ahead to a post-Oscars existence, he did his best to sound resolute. “I do feel extraordinary about this, but after Sunday, it’s time to let go without regard for awards,” he said. “Now, how possible is that?”

Zhao took the stage for Best Director and brought the mood home. “I’ve been thinking a lot lately how I’ve kept going when things get hard,” she said. When “Nomadland” won Best Picture, the distributor for a competing film wrote me: “I love Chloe. This is fine. I’m not grieving.”

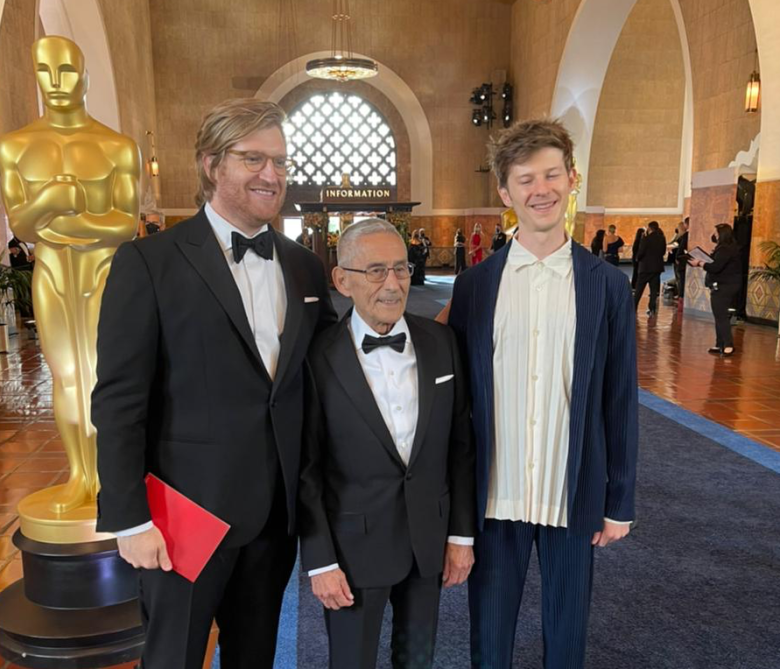

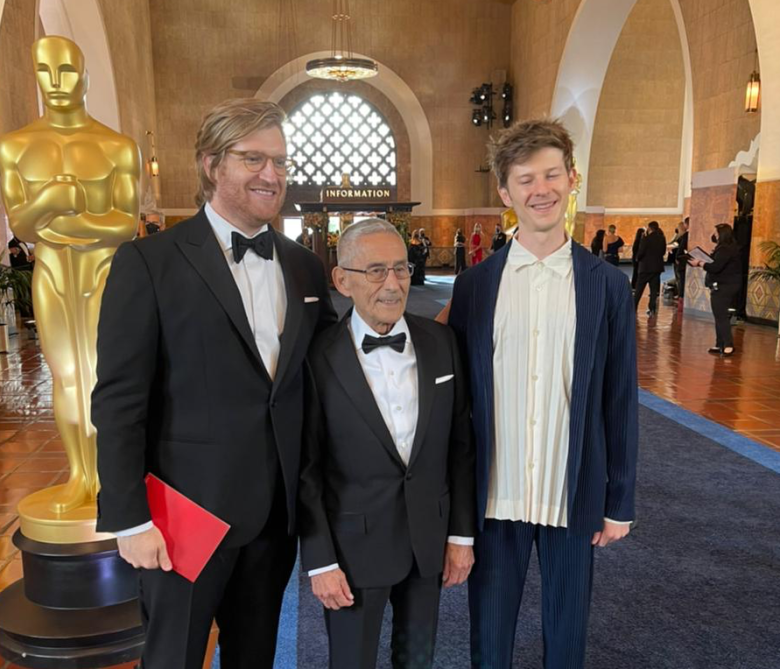

“Nomadland” producer Dan Janvey at the 93rd Academy Awards with “The Mole Agent” subject Sergio Chamy and “Time” producer Kellen Quinn

Outside the ceremony, Janvey finally got his photo with Chamy. “You made such a beautiful and kind and soulful movie,” he told Alberdi, who complimented “Nomadland” in turn. “It’s the way we understand cinema,” she said.

Janvey had plenty of reasons to sound confident about his work, but insisted there was more to it than his golden trophy. “Look, it’s been a long year,” he said. “I don’t think the Oscars have that sense that it’s all over.” He pulled “Time” producer Kellen Quinn into the photo with Chamy. “I’m thinking about how we are all having the chance to be together safely and celebrate movies,” Janvey said. “It may be the first Oscars where anybody who says they’re just happy to be there … seriously, seriously means that.”

He wasn’t alone. Just as the Oscars weekend began, an awards publicist texted me: “Can’t wait until we have the normal Oscar-week circuit again.”

The “Sound of Metal” writer and director, who was up for two awards and would win neither, had spent the last few days in a last-minute campaign sprint for his drama about a deaf addict while jugging a few commercial shoots. Talking on the phone while he wandered the streets, Marder spoke breathlessly about the psychological effect of getting an 11-year passion project made, only to reiterate that story in the endless zooming of a pandemic awards season.

“You spent a lot of time thinking about this final frontier of recognition, this peer acknowledgement. But here’s what I know,” he said. “What I know is that this film is what it is because I could give a flying fuck about these awards. I was never making the film for that reason. It has never been about pandering or playing any game other than serving the movie in its truest form.”

That was the overarching sentiment of a weird Oscar weekend when everything felt so constrained that it was a wonder the awards themselves weren’t adorned in tiny masks. Following the proceedings from New York, I called and texted with nominees as the ceremony drew near. Many said they expected to lose — and did. There was more interest in discussing self-preservation than regarding the glow of a socially distant red carpet. With the state of exhibition uncertain as COVID-19 continued to rage worldwide, I heard more battle cries about keeping the art form alive than pleas to keep the business intact.

Some took in the mythological dimensions. Danish auteur Thomas Vinterberg, whose Best International Feature win for “Another Round” would be an early emotional highlight of the show, told me he and his wife spent a week of quarantine high in the Hollywood Hills, homeschooling their kids and watching “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” after they went to a bed “with a whiskey sour in our hands.” He marveled at Charlie Chaplin’s old house nearby. “I am imagining what must have happened there,” he said.

Others already planned next steps. “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” breakout Maria Bakalova was an unknown Bulgarian actress less than a year ago; now the 24-year-old juggled final Oscar duties with plans to launch a production company with fellow Bulgarian Julian Kostov to support more Eastern Europeans in the film industry. “I want to advocate for equal representation as well as the normalization of foreign accents on screen and shedding negative stereotypes,” she said. “Diversity is crucial to our industry.”

That mentality, crucial to the Oscar-season narrative in recent years yet often reduced to soundbites, hovered uncomfortably at the center of a surreal ceremony. Staged like a movie (and at times, it looked as visually dynamic), familiar dramas brought it down to Earth. Black actors were shut out of top performance categories, right down to the stinging finale. With most nominees unfamiliar to mainstream audiences, the show gave the unfortunate impression of an industry struggling to maintain its relevance. The letterboxed aspect ratio opened up the frame, but everyone looked constrained: a hip crowd, shunted into the corner of popular culture.

For many nominees whose work already falls outside of the system, that outcome is business as usual. A sense of smallness, with its preordained bad ratings and pathetic box office, felt not unlike the marginalization experienced by many filmmakers on the regular even when they muster a modicum of professional recognition.

Chloé Zhao on Oscar night

“Nomadland” director Chloé Zhao touched on that sentiment hours before her historic pair of Oscar wins, for Best Director and Best Picture, while talking to a red carpet interviewer before the show. She spent three months making her Best Picture winner on the road and in secret, with mostly non-professional actors on a $5 million budget. “Sometimes,” she said, “filmmaking can be a quite lonely, and transient, experience.”

The triumph of that gutsy, experimental swing, one year after “Parasite” dominated the Oscars, illustrated the divide between uniform crowdpleasers that drive studios’ quarterly reports and the individualism that compels the strongest directors to stay in the game.

“To me, this year’s Oscars reflect an intuitive state of where cinema is going,” said “Nomadland” producer Dan Janvey the day before his Best Picture win. “Whether or not Hollywood is OK with that — or even realizes that — it’s tremendously exciting to me. These are just thrilling movies.”

Janvey, a veteran of the filmmaking collective Court 13, last made the awards-season rounds as a nominee behind Benh Zeitlin’s “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” a film that taught him about the practical challenges of shooting on the fly in real places. “The last time we did this, I don’t think we were actively trying to win anything,” he said. “There was just a gleefulness about being in some of those rooms.” (Janvey also co-produced Best Documentary nominee “Time,” a black-and-white repudiation of the criminal justice system that deserved to win.)

“We try to generalize the Oscars into a state of cinema,” Janvey said. “The truth is that cinema has a lot of different moments where that happens for different bodies of people. Cannes, to me, is Rosh Hashanah. Maybe the Oscars are Passover. The point is, if you want to look at the Oscars as a state of where the industry and people who make movies, I think overall this year’s nominees are historically incredible.”

More than that, he added: “If your orientation is more toward global cinema than just the studio cinema, there’s something exciting about where the Oscars are pushing the conversations. I think of Chloé in that context.”

“Nomadland”

Searchlight

Like many nominees, Janvey felt hampered by the virtual nature of the campaign process. “You don’t get that sense of talking to the other filmmakers about their work, and it’s really sad,” he said. “That’s one of the more special moments of being in a film community — that kind of sharing of work.”

Looking ahead to the show, Janvey was keen to connect with Sergio Chamy, the 83-year-old subject of Chilean Best Documentary nominee “The Mole Agent,” who infiltrated a nursing home in the movie; his Oscar attendance marked his first trip to America. “The number-one person I want to meet and take a picture with is Sergio,” he said. “So much attention is given to the horse race component and there’s actually another really, really beautiful aspect of it that gets less attention.”

Later, I connected Janvey with “The Mole Agent” director Maite Alberdi on a WhatsApp chain and they began to swap enthusiasm for each other’s work while plotting the photo opp at Union Station. Alberdi said the trip to L.A. was a particularly disorienting experience as her native Santiago remains in lockdown.

“We did not believe we could be here,” she told me on Saturday. Without the budgetary resources to mount an aggressive campaign, Alberdi and her team built an online DIY effort that actually benefited from the unorthodox year. “If I had to spend a million dollars on a campaign and invite everyone to cocktails and put up big posters in every city, I’d never do it,” she said. “This film was financed mostly from public television. It’s impossible to create a traditional Oscar campaign with that.”

Over the past year, she juggled everyday life with endless promotional duties. “I could go pick up my son at kindergarten every day in Chile and still run my Oscar campaign. That was unbelievable,” she said. “I think the pandemic definitely impacted the relationship that we have with the audience in theater, but on the other hand, I think I did more Q&As in different parts of the world because I couldn’t travel. I thought the film was going to be lost in the sea of films during the pandemic. Instead, it was more visible.” The movie landed on the Best International Film and Best Documentary shortlists; it was the first Chilean documentary to be nominated.

Alberdi said the ongoing pandemic meant she can’t resume her intimate approach to non-fiction, which turns on eccentric characters like Chamy. “This is the first time in 11 years that I haven’t shot a new film for a whole year,” she said, recalling how she had to pause production when shutdowns took hold. “I cannot apply COVID protocols to continue shooting vulnerable characters who I cannot put at risk. I don’t know when I’ll use the camera again, and that is really frustrating.”

A few thousand miles away in the United Kingdom, Field of Vision cofounder and Best Documentary Short nominee Charlotte Cook watched the show with her parents under quarantine. When her father booked an embolism-related surgery days before the broadcast, she decided to stay home. Given the late hour of the program, her mother bought fancy pajamas for the experience. “It’s a strange experience,” said Cook, who produced “Do Not Split,” “but family comes first.”

Nominations for “Do Not Split,” which details the recent Hong Kong protests against the oppressive Chinese government, resulted in the broadcast being banned in China. “The day after my nomination, I spent hours on the phone with lawyers,” Cook said. “We imagined there would be some kind of response, but not on that level.” Working with the film’s Norwegian director, Anders Hammer, Cook used the fleeting attention of the Oscar nomination to raise awareness of the ongoing dangers faced by Hong Kong citizens who push back on Mainland censorship. “We are both privileged people, being white and European and having safety in this moment to speak about this issue,” she said. “We’ve had to balance what our film is about and what we’re trying to talk with this odd experience of being celebrated. This is not something that’s in the past. It’s happening now.”

Just last week, she added, another documentary producer in Hong Kong was convicted by the Chinese government. “This is something we have to talk about,” she said. For her, the Zoom-based campaigning process limited social opportunities but it also enabled international stories to travel. “That’s a barrier that’s been broken,” she said.

Catalin Tolontan in “Collective”

A beneficiary of that shift was Alexander Nanau, the Romanian director whose “Collective” landed nominations for both Best Documentary and Best International Film. A bracing real-time thriller as its journalist subjects unearth a healthcare scandal at the highest levels of the Romanian government, the movie documents a failing democracy and the passionate efforts to decry its collapse. “I continue to feel thankful for all that the Oscar nominations have done for our film around the world,” Nanau told me. “The surprise of the campaign was to see that even though we had so many restrictions from the pandemic, movies can travel.”

For the 2021 Oscars, travel became a synonym for thousands of Zoom panels Marder guessed that he participated in upward of 300 promotional Zooms to support “Sound of Metal,” and that was a conservative estimate.

“Zooms are inherently exhausting,” he said. “They just require attention and there’s just an awkwardness to them. You just feel like you’re putting out energy all the time.” At the same time, he treasured the recurring opportunities to see his “Sound of Metal” collaborators, even in little digital boxes at the mercy of tenuous wifi connections. “We all found each other texting afterwards,” he said. “In isolation, these Zooms turned into a lifeline for us.”

During the show, Marder celebrated as “Sound of Metal” scored Best Editing and Best Sound. “I had to engage in a process of educating people about the relationship between editing and sound in this film,” he beamed. “I saw that take root.” Looking ahead to a post-Oscars existence, he did his best to sound resolute. “I do feel extraordinary about this, but after Sunday, it’s time to let go without regard for awards,” he said. “Now, how possible is that?”

Zhao took the stage for Best Director and brought the mood home. “I’ve been thinking a lot lately how I’ve kept going when things get hard,” she said. When “Nomadland” won Best Picture, the distributor for a competing film wrote me: “I love Chloe. This is fine. I’m not grieving.”

“Nomadland” producer Dan Janvey at the 93rd Academy Awards with “The Mole Agent” subject Sergio Chamy and “Time” producer Kellen Quinn

Outside the ceremony, Janvey finally got his photo with Chamy. “You made such a beautiful and kind and soulful movie,” he told Alberdi, who complimented “Nomadland” in turn. “It’s the way we understand cinema,” she said.

Janvey had plenty of reasons to sound confident about his work, but insisted there was more to it than his golden trophy. “Look, it’s been a long year,” he said. “I don’t think the Oscars have that sense that it’s all over.” He pulled “Time” producer Kellen Quinn into the photo with Chamy. “I’m thinking about how we are all having the chance to be together safely and celebrate movies,” Janvey said. “It may be the first Oscars where anybody who says they’re just happy to be there … seriously, seriously means that.”

He wasn’t alone. Just as the Oscars weekend began, an awards publicist texted me: “Can’t wait until we have the normal Oscar-week circuit again.”