I always imagined that Hayao Miyazaki’s “My Neighbor Totoro” would be the first movie I ever showed my son. But sometime last summer — about 30 minutes into an eight-hour flight, or roughly 29 minutes after his 2-year-old mind grew bored with sitting inside a massive steel tube as it rocketed across the sky at 300 mph — I delegated the honor of choosing Asa’s first movie to the fine people who program Delta’s in-flight entertainment.

The options were rather uninspiring (you can’t bring a bottle of water through security, but “Sing 2” is safe?), and even the higher-quality fare seemed like it might fry my kid’s brain. It wasn’t until I neared the end of my A-Z search that something jumped out at me as a viable option. Not only was it a great film, but its frequently wordless storytelling also meant that I’d be able to watch along from the next seat without a pair of headphones. But the real deciding factor was that — despite my deeply ingrained resentment towards the look and gentrification-like energy of computer-generated Hollywood cartoons — this one somehow promised not to betray my pretentious and ridiculously parent-brained plan of introducing Asa to the movies by showing him one that reflects the most basic essence of their magic. Even with Disney’s entire library at my disposal, it’s hard to imagine I could have found a better choice.

The movie, of course, was “WALL-E,” and my son watched it something like six times in a row before we landed (he alternated between taking serene naps and making Spielberg faces up at the seat-back screen). In the months since, I’ve seen at least half of Andrew Stanton’s fantastic post-apocalyptic fable approximately once a day — twice if it’s raining — and have scrambled to turn off my Apple TV before it auto-played “Cars” more times than I can count.

That might sound masochistic, but I regret to inform you that it’s a distressingly standard media diet for someone with a young child and a Disney+ account; most toddlers would beg for the Ludovico Technique by name if they knew what it was called. In truth, the only strange thing about it is that I haven’t gotten sick of “WALL-E” either.

And when it was unexpectedly announced that the movie would be inducted into the Criterion Collection with a deluxe 4K UHD edition — placing it alongside the likes of canonical masterpieces like “Pather Panchali,” “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” and “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” — it felt as if the universe itself validated my first major cinematic parenting decision.

But it wasn’t until I had the Criterion disc in my hands that I fully realized how fortunate I’d been to find “WALL-E” on our flight that day. For obvious reasons, “WALL-E” is often seen as a cautionary tale about the ravages of climate change and/or a kid-friendly critique of the same consumer capitalism that helped Disney foot the bill for its $180 million budget in the first place. But its most profound joys are rooted in something much simpler: Robots acting like humans to teach humans how to stop acting like robots (and giant babies).

Stanton literally spent years trying to wrestle that notion into a specific sentence that might keep his massive team at Pixar on the same page during production. “It sounds stupid,” he told me on a recent Zoom call, “but sometimes you don’t see your work for weeks or months as it moves down the pipeline; when you can [spell out a project’s theme] like a catchphrase on a coffee mug, you know that the army of people along the chain isn’t putting the wrong clothes on your child. Everybody can be helping you towards the same north star.”

The catchphrase that Stanton eventually came up with is “irrational love defeats life’s programming.” Seeing the page from his notebook recreated in the liner notes of Criterion’s Blu-ray, I finally understood why “‘WALL-E” is such a perfect movie for parents to watch 900 times with their kids: In a certain light, it’s a movie about parenting.

More specifically, it’s a movie about the sweet vertigo of that transition from experiencing the world first-hand to showing it to someone else; a movie that pushes against the inertia of being alive as its characters strive to hold onto the past without getting stuck in it and make way for tomorrow without forgetting yesterday.

“That’s because parenting is programming,” Stanton said when I presented this theory to him, his inflection on that last word allowing it to land as both a noun and a verb all at once. The two concepts are so intertwined that Stanton couldn’t avoid pairing them together in “WALL-E,” even if the word “parenthood” never appeared in his notebook. “It has to have gotten in there subconsciously,” Stanton said, “because I felt I had run every ounce of what I had to say about parenthood in ‘Finding Nemo,’ and my kids were already going into high school by the time I started this one. But I’m just immature enough for the wonder part to never go away, and that’s true of anyone who was in our Pixar group at the time. The insatiable hunger to feed curiosity is just innate and ongoing — it’s perpetual. And so if that feels associated with childhood or parenting I think that’s just an ingredient that’s baked into anything I do, maybe even to a fault at times.”

“Wall-E”

The film’s more deliberate pleasures are both obvious and abundant, as Stanton dusts them over deep layers of historical sediment in a way that allows “WALL-E” to hit similarly whether it’s your first movie or your 5,000th and crush time into a flat circle with the same ease that its title character crunches post-apocalyptic scrap metal into perfect little cubes. Those joys naturally begin with WALL-E himself (Stanton’s robots are rather aggressively genderized), one of the most delightful and expressive characters ever created for an animated film.

A puppy-eyed trash compactor who rolls around the rusted orange wasteland of life after capitalism with no one for company save for an unkillable cockroach friend, WALL-E is powered by the sun but kept alive by his childlike sense of wonder for the relics he finds in the abandoned ruins of 29th-century New York City. A lighter. A spork. An original iPod — already borderline ancient to 21st-century audiences — loaded with a copy of Gene Kelly’s 1969 movie adaptation of “Hello, Dolly!” WALL-E’s love for these objects has somehow preserved them in the face of post-apocalyptic degradation, and they have preserved him in return.

In an essay included with the Criterion Blu-ray, author Sam Wasson describes WALL-E as “the last moviegoer on Earth,” but even if that weren’t the case, he would still probably be the last person on the planet watching “Hello, Dolly!” (a film that critic Vincent Canby dismissed at the time of its release by writing that it “adds nothing to the heritage of the musical screen except statistics”).

WALL-E adores it, and not only because he tends to be more of a Pauline Kael guy; through his endearing binocular eyes, which audibly shift their focus with every new discovery in a way that allows you to feel the vicarious thrill of seeing even his ruined world for the first time, we come to adore it too. “I’m not a huge Broadway musical guy,” Stanton said of the choice to foreground “Hello, Dolly!,” “but I consciously wanted to indulge in the romantic nature of looking at life, which feels musical to me, and I felt like this film’s dark apocalyptic veneer freed me to go a little nuts with how romantic I really like to be.”

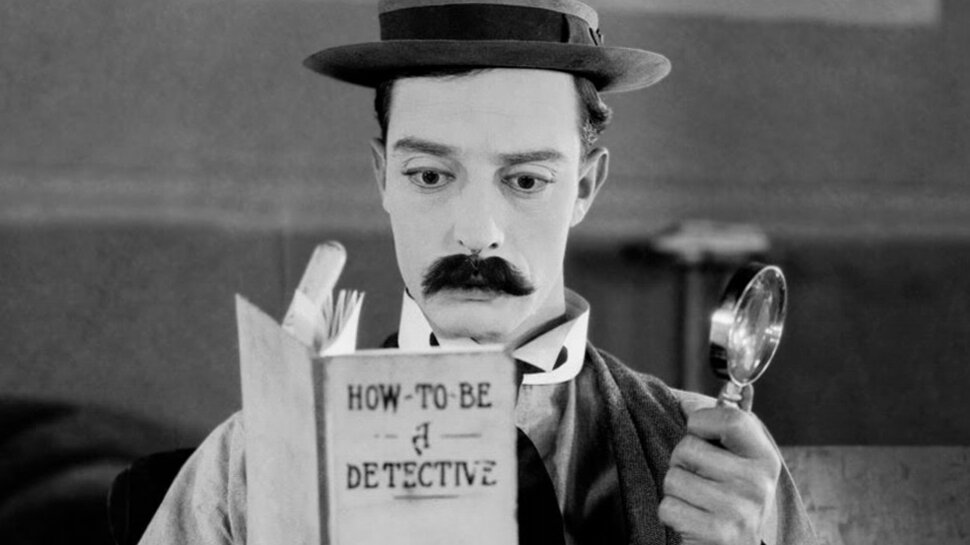

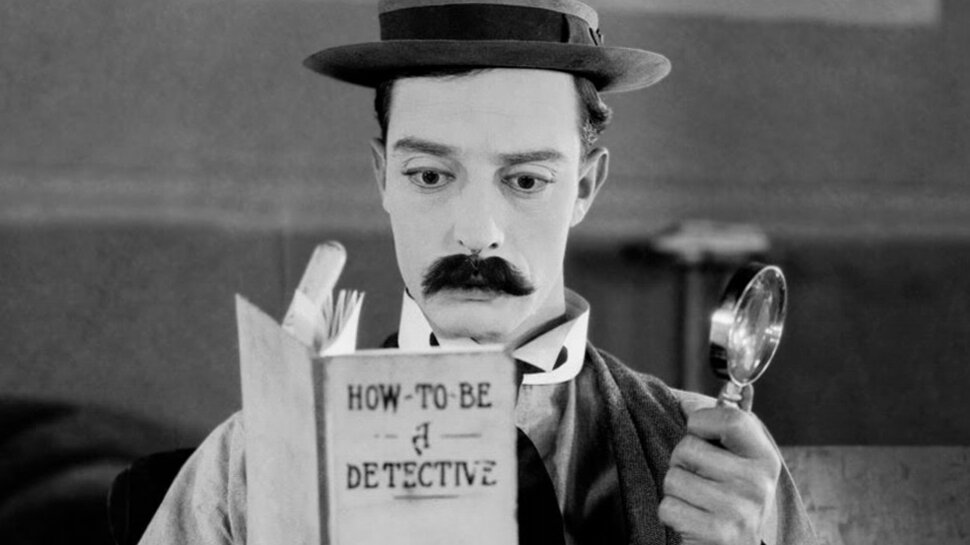

“Sherlock Jr.”

But Stanton’s movie also reverberates with the echoes of cinema’s more recognizable touchstones, even as it savors the irony that some misbegotten Barbra Streisand/Walter Matthau musical has outlasted them all. WALL-E — who only speaks in a limited vocabulary of auto-tuned names and exclamations, despite the vast emotional range of Ben Burtt’s voice performance — was famously inspired by silent film stars like Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, and when an Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator (EVE) comes down to Earth in search of plant life, our lovelorn hero swoons over her with the same klutzy sweetness that once defined romance in some very different modern times. “‘WALL-E’ has always meant the most to me [of all my work] because of its genesis,” Stanton said. “It was a love letter to everything about cinema that I took in as a youth.”

For Stanton, that influence traces back to a weekly Keaton festival at the local cinema when he (along with several of the people he would go on to collaborate with at Pixar) was a student at Cal Arts. “Because we were students with no lives, we could go down and do this every Monday night,” Stanton remembered. “We’d sit in a packed house for four hours and basically get to be in a time machine — that’s how it felt with an organ player and an audience that you could hear go through every emotion watching something that was 70 years old. We felt like we knew everything about cinema and were the filmmakers of the future, only to be humbled and sobered by the fact that, oh, they had everything and we’ve lost it. It was all there in the simplicity, but the complexity was disguised in each one of the pieces because life is fractal like that. It’s that Italian word ‘Sprezzatura,” which is the art of concealing art, but it only comes through when you find the truth of something, and Keaton was doing that in spades. It became like a drug — our church. It never left me.”

Thanks to the genius of Stanton’s team, the sight of WALL-E clinging to the side of a rocket ship hits the same note of composed panic that’s etched across the Projectionist’s face in “Sherlock Jr.” Thanks to the clarity of Stanton’s vision, the movie’s final scene can recast the ending of “City Lights” with CGI robots in a way that feels as focused on the future as it is indebted to the past.

“City Lights”

And thanks to the sheer intractability of Stanton’s influences, which spread far beyond the silent era and run much deeper than mere homage, the uproarious cackling that “WALL-E” can elicit from my kid sounds like a distant echo of the laughter that “Playful Pluto” inspires from its audience of dispossessed wretches during the last reel of “Sullivan’s Travels.” (Likening a Brooklyn daycare student to a Depression-era labor camp worker feels like the same kind of delusional thinking that leads a lonely robot to take his romantic cues from a Hollywood musical.)

“I knew deep in my cinematic soul what gave birth to this movie,” Stanton said, “and it felt like The Criterion Collection almost deserved some of the parenthood.” That lineage is backed up by a lovely documentary on the Blu-ray in which Stanton reflects on his time as an usher at an arthouse theater and traces “WALL-E” back to the likes of “The Red Balloon,” “The Black Stallion,” and “My Life as a Dog” — all of which Criterion released at one time or another.

Had Criterion announced that it was releasing any of Pixar’s other films (even something as totemic as “Toy Story” or as sophisticated as “Ratatouille”), I would have been somewhat confused, and recent news of the company’s unfortunate “reorganization” would probably have seemed even more alarming to me than it already did. Likewise, had I not spent the previous few months watching Stanton’s movie on a near-constant loop, I probably would’ve been more skeptical about the extent — or at least the value — of the influence that early cinema and arthouse classics supposedly had on his summer blockbuster about a sentient trash compactor who’s obsessed with Streisand.

But this strange marriage between a boutique arthouse label and the biggest Disney movie of 2008 has started to make a lot of sense to me, not only because I’ve been convinced (or Stockholm Syndrome-d) into believing that my pal WALL-E is as worthy an heir to Buster Keaton as Jackie Chan was to Charlie Chaplin, but also because I’ve come to appreciate how “WALL-E” offered the world’s preeminent distributor of important classic and contemporary cinema a unique chance to meaningfully bridge the gap between the two different parts of its mission statement.

The unmistakable modernity of Stanton’s film — epitomized by its fluid and lifelike use of the same CGI animation that can sometimes feel like an affront to the artistry of the traditional 2D style — is the very thing that allows it to be such a brilliant vessel for the old school pleasures that it offers to a new generation of young viewers, and also such an effective push for parents to let their kids move beyond the past. We hold them back, and they push us forward so that nobody gets stuck in a rut; the Earth may be locked in its orbit, but our circular journey around the sun only moves forward.

And Stanton already can’t wait for someone to take the next step. “It’s been 30 years since ‘Toy Story,’” he said. “I really hope that I live long enough that we’re shamed into a whole different way of looking at animated movies. Because yeah, you want to inspire people, but all I ever hope for in any movie is that it doesn’t just repeat what’s already been done.”

The Criterion Collection edition of “WALL-E” is now available in stores.

The options were rather uninspiring (you can’t bring a bottle of water through security, but “Sing 2” is safe?), and even the higher-quality fare seemed like it might fry my kid’s brain. It wasn’t until I neared the end of my A-Z search that something jumped out at me as a viable option. Not only was it a great film, but its frequently wordless storytelling also meant that I’d be able to watch along from the next seat without a pair of headphones. But the real deciding factor was that — despite my deeply ingrained resentment towards the look and gentrification-like energy of computer-generated Hollywood cartoons — this one somehow promised not to betray my pretentious and ridiculously parent-brained plan of introducing Asa to the movies by showing him one that reflects the most basic essence of their magic. Even with Disney’s entire library at my disposal, it’s hard to imagine I could have found a better choice.

The movie, of course, was “WALL-E,” and my son watched it something like six times in a row before we landed (he alternated between taking serene naps and making Spielberg faces up at the seat-back screen). In the months since, I’ve seen at least half of Andrew Stanton’s fantastic post-apocalyptic fable approximately once a day — twice if it’s raining — and have scrambled to turn off my Apple TV before it auto-played “Cars” more times than I can count.

That might sound masochistic, but I regret to inform you that it’s a distressingly standard media diet for someone with a young child and a Disney+ account; most toddlers would beg for the Ludovico Technique by name if they knew what it was called. In truth, the only strange thing about it is that I haven’t gotten sick of “WALL-E” either.

And when it was unexpectedly announced that the movie would be inducted into the Criterion Collection with a deluxe 4K UHD edition — placing it alongside the likes of canonical masterpieces like “Pather Panchali,” “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” and “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” — it felt as if the universe itself validated my first major cinematic parenting decision.

But it wasn’t until I had the Criterion disc in my hands that I fully realized how fortunate I’d been to find “WALL-E” on our flight that day. For obvious reasons, “WALL-E” is often seen as a cautionary tale about the ravages of climate change and/or a kid-friendly critique of the same consumer capitalism that helped Disney foot the bill for its $180 million budget in the first place. But its most profound joys are rooted in something much simpler: Robots acting like humans to teach humans how to stop acting like robots (and giant babies).

Stanton literally spent years trying to wrestle that notion into a specific sentence that might keep his massive team at Pixar on the same page during production. “It sounds stupid,” he told me on a recent Zoom call, “but sometimes you don’t see your work for weeks or months as it moves down the pipeline; when you can [spell out a project’s theme] like a catchphrase on a coffee mug, you know that the army of people along the chain isn’t putting the wrong clothes on your child. Everybody can be helping you towards the same north star.”

The catchphrase that Stanton eventually came up with is “irrational love defeats life’s programming.” Seeing the page from his notebook recreated in the liner notes of Criterion’s Blu-ray, I finally understood why “‘WALL-E” is such a perfect movie for parents to watch 900 times with their kids: In a certain light, it’s a movie about parenting.

More specifically, it’s a movie about the sweet vertigo of that transition from experiencing the world first-hand to showing it to someone else; a movie that pushes against the inertia of being alive as its characters strive to hold onto the past without getting stuck in it and make way for tomorrow without forgetting yesterday.

“That’s because parenting is programming,” Stanton said when I presented this theory to him, his inflection on that last word allowing it to land as both a noun and a verb all at once. The two concepts are so intertwined that Stanton couldn’t avoid pairing them together in “WALL-E,” even if the word “parenthood” never appeared in his notebook. “It has to have gotten in there subconsciously,” Stanton said, “because I felt I had run every ounce of what I had to say about parenthood in ‘Finding Nemo,’ and my kids were already going into high school by the time I started this one. But I’m just immature enough for the wonder part to never go away, and that’s true of anyone who was in our Pixar group at the time. The insatiable hunger to feed curiosity is just innate and ongoing — it’s perpetual. And so if that feels associated with childhood or parenting I think that’s just an ingredient that’s baked into anything I do, maybe even to a fault at times.”

“Wall-E”

The film’s more deliberate pleasures are both obvious and abundant, as Stanton dusts them over deep layers of historical sediment in a way that allows “WALL-E” to hit similarly whether it’s your first movie or your 5,000th and crush time into a flat circle with the same ease that its title character crunches post-apocalyptic scrap metal into perfect little cubes. Those joys naturally begin with WALL-E himself (Stanton’s robots are rather aggressively genderized), one of the most delightful and expressive characters ever created for an animated film.

A puppy-eyed trash compactor who rolls around the rusted orange wasteland of life after capitalism with no one for company save for an unkillable cockroach friend, WALL-E is powered by the sun but kept alive by his childlike sense of wonder for the relics he finds in the abandoned ruins of 29th-century New York City. A lighter. A spork. An original iPod — already borderline ancient to 21st-century audiences — loaded with a copy of Gene Kelly’s 1969 movie adaptation of “Hello, Dolly!” WALL-E’s love for these objects has somehow preserved them in the face of post-apocalyptic degradation, and they have preserved him in return.

In an essay included with the Criterion Blu-ray, author Sam Wasson describes WALL-E as “the last moviegoer on Earth,” but even if that weren’t the case, he would still probably be the last person on the planet watching “Hello, Dolly!” (a film that critic Vincent Canby dismissed at the time of its release by writing that it “adds nothing to the heritage of the musical screen except statistics”).

WALL-E adores it, and not only because he tends to be more of a Pauline Kael guy; through his endearing binocular eyes, which audibly shift their focus with every new discovery in a way that allows you to feel the vicarious thrill of seeing even his ruined world for the first time, we come to adore it too. “I’m not a huge Broadway musical guy,” Stanton said of the choice to foreground “Hello, Dolly!,” “but I consciously wanted to indulge in the romantic nature of looking at life, which feels musical to me, and I felt like this film’s dark apocalyptic veneer freed me to go a little nuts with how romantic I really like to be.”

“Sherlock Jr.”

But Stanton’s movie also reverberates with the echoes of cinema’s more recognizable touchstones, even as it savors the irony that some misbegotten Barbra Streisand/Walter Matthau musical has outlasted them all. WALL-E — who only speaks in a limited vocabulary of auto-tuned names and exclamations, despite the vast emotional range of Ben Burtt’s voice performance — was famously inspired by silent film stars like Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, and when an Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator (EVE) comes down to Earth in search of plant life, our lovelorn hero swoons over her with the same klutzy sweetness that once defined romance in some very different modern times. “‘WALL-E’ has always meant the most to me [of all my work] because of its genesis,” Stanton said. “It was a love letter to everything about cinema that I took in as a youth.”

For Stanton, that influence traces back to a weekly Keaton festival at the local cinema when he (along with several of the people he would go on to collaborate with at Pixar) was a student at Cal Arts. “Because we were students with no lives, we could go down and do this every Monday night,” Stanton remembered. “We’d sit in a packed house for four hours and basically get to be in a time machine — that’s how it felt with an organ player and an audience that you could hear go through every emotion watching something that was 70 years old. We felt like we knew everything about cinema and were the filmmakers of the future, only to be humbled and sobered by the fact that, oh, they had everything and we’ve lost it. It was all there in the simplicity, but the complexity was disguised in each one of the pieces because life is fractal like that. It’s that Italian word ‘Sprezzatura,” which is the art of concealing art, but it only comes through when you find the truth of something, and Keaton was doing that in spades. It became like a drug — our church. It never left me.”

Thanks to the genius of Stanton’s team, the sight of WALL-E clinging to the side of a rocket ship hits the same note of composed panic that’s etched across the Projectionist’s face in “Sherlock Jr.” Thanks to the clarity of Stanton’s vision, the movie’s final scene can recast the ending of “City Lights” with CGI robots in a way that feels as focused on the future as it is indebted to the past.

“City Lights”

And thanks to the sheer intractability of Stanton’s influences, which spread far beyond the silent era and run much deeper than mere homage, the uproarious cackling that “WALL-E” can elicit from my kid sounds like a distant echo of the laughter that “Playful Pluto” inspires from its audience of dispossessed wretches during the last reel of “Sullivan’s Travels.” (Likening a Brooklyn daycare student to a Depression-era labor camp worker feels like the same kind of delusional thinking that leads a lonely robot to take his romantic cues from a Hollywood musical.)

“I knew deep in my cinematic soul what gave birth to this movie,” Stanton said, “and it felt like The Criterion Collection almost deserved some of the parenthood.” That lineage is backed up by a lovely documentary on the Blu-ray in which Stanton reflects on his time as an usher at an arthouse theater and traces “WALL-E” back to the likes of “The Red Balloon,” “The Black Stallion,” and “My Life as a Dog” — all of which Criterion released at one time or another.

Had Criterion announced that it was releasing any of Pixar’s other films (even something as totemic as “Toy Story” or as sophisticated as “Ratatouille”), I would have been somewhat confused, and recent news of the company’s unfortunate “reorganization” would probably have seemed even more alarming to me than it already did. Likewise, had I not spent the previous few months watching Stanton’s movie on a near-constant loop, I probably would’ve been more skeptical about the extent — or at least the value — of the influence that early cinema and arthouse classics supposedly had on his summer blockbuster about a sentient trash compactor who’s obsessed with Streisand.

But this strange marriage between a boutique arthouse label and the biggest Disney movie of 2008 has started to make a lot of sense to me, not only because I’ve been convinced (or Stockholm Syndrome-d) into believing that my pal WALL-E is as worthy an heir to Buster Keaton as Jackie Chan was to Charlie Chaplin, but also because I’ve come to appreciate how “WALL-E” offered the world’s preeminent distributor of important classic and contemporary cinema a unique chance to meaningfully bridge the gap between the two different parts of its mission statement.

The unmistakable modernity of Stanton’s film — epitomized by its fluid and lifelike use of the same CGI animation that can sometimes feel like an affront to the artistry of the traditional 2D style — is the very thing that allows it to be such a brilliant vessel for the old school pleasures that it offers to a new generation of young viewers, and also such an effective push for parents to let their kids move beyond the past. We hold them back, and they push us forward so that nobody gets stuck in a rut; the Earth may be locked in its orbit, but our circular journey around the sun only moves forward.

And Stanton already can’t wait for someone to take the next step. “It’s been 30 years since ‘Toy Story,’” he said. “I really hope that I live long enough that we’re shamed into a whole different way of looking at animated movies. Because yeah, you want to inspire people, but all I ever hope for in any movie is that it doesn’t just repeat what’s already been done.”

The Criterion Collection edition of “WALL-E” is now available in stores.