[Editor’s note: The following story contains spoilers for “Thor: Love and Thunder.”]

Superhero films have a long, fraught history with the depiction of disability. Often, these films’ disabled characters are portrayed as villains, like Dr. Poison in “Wonder Woman” or Samuel L. Jackson’s Elijah Price in “Unbreakable.” Most, like DC’s Doctor Mid-Nite, haven’t yet been considered worthy of bringing into the cinematic world. And when these characters do appear in sprawling movie and TV franchises, they are often played by non-disabled actors (such is the case with “Daredevil” or Professor X in “X-Men.”)

There’s no dearth of these kinds of heroes and villains in comic books: Disabled superheroes have been around since the 1940s, with Doctor Mid-Nite — who can see in the dark but is blind at night — widely considered the first disabled superhero. Others include Oracle, otherwise known as Barbara Gordon, who became the hero after being paralyzed; the inventive Komodo, a double amputee who has the power to regrow limbs; and the Hornet, who has cerebral palsy.

But while superhero stories reign supreme at the box office and beyond, translating this wide variety of disabled superheroes to screens both large and small has been frustratingly delayed.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has certainly tried its hand at touching on disability in their features, though with about as much success and nuance as its portrayal of LGBTQ characters. Taika Waititi’s latest entry in the “Thor” series won’t rewrite the book on disability portrayals in Marvel movies, but the film’s treatment of Dr. Jane Foster (Natalie Portman) as the Mighty Thor offers some compelling new ideas.

“Thor: Love and Thunder”

Jasin Boland

“Love and Thunder” condenses a lot of Jane’s cancer journey from the comics. Jane was diagnosed with cancer in the comics in 2012, losing her own mother to the disease first, as also depicted in the film. In the comics, Jane initially refuses any magical help from Thor, and his mighty hammer Mjolnir reaches out to her through a telepathic link between the two, as opposed to Waititi’s film, in which a flashback shows Thor commanding Mjolnir to protect Jane. In both the film and comic storyline, once Jane picks up Mjolnir, she becomes the Mighty Thor (though, in the comics, it takes Thor a bit longer to figure out his ex is under the helmet).

Jane’s predominant aim in Waititi’s feature is to help a lost Thor (Chris Hemsworth) realize he does want family, love, and community in his life, but her own narrative feels far closer to a conflicted disabled story, as she struggles to deal with her cancer diagnosis.

In other superhero movies — including those created by both Marvel and DC — Jane’s cancer would easily be cured by the implementation and utilization of superpowers. Such is the case with the 2019 feature “Shazam!” and the character of Freddy Freeman (Jack Dylan Grazier). Freeman is the best friend of the title character, AKA Billy Batson (played by Asher Angel), who uses a crutch due to an unexplained disability.

There’s a lot to praise about Freddy, especially as much of the film’s humor is centered around poking fun at how able-bodied people look at disabled people. (When wise-cracking Freddy first meets Billy he describes himself as a “disabled foster kid” who, presumably, should “have it all.”)

“Shazam!”

Warner Bros.

But in the film’s third act, when Billy needs his foster family to help him, and the magical powers of Shazam are shared between the other foster children, Freddy “reaches his full potential” by becoming a grown-up — and able-bodied — character played by Adam Brody. “Shazam!” ends before we see Freddy grapple with this newfound “cure,” but the idea that to reach one’s “full potential,” they will be non-disabled stings and relies on outdated ideas that having a disability is something that, ultimately, should — and could — be cured.

“Love and Thunder” is often a stark exploration of religion and death, and much of what fuels Jane is her desire to live. She doesn’t feel she’s done with the work she’s pioneered (both in science and, later, as the Mighty Thor) and is willing to take any cure presented to her.

In this case, the power of Thor’s broken hammer, Mjolnir, is (at least temporarily) that cure for her. Jane pieces it back together and becomes the buff, blonde Mighty Thor. Problem solved, right? But when Jane picks up Mjolnir and becomes Mighty Thor, her sudden superhero powers aren’t framed as any sort of cure-all. It’s a temporary stop-gap, a badass and supercharged example of durable medical equipment.

It won’t “fix” anything, only delay her illness and help Jane live the rest of her life in a literally more powerful manner. Interestingly, in the comics Jane’s demise plays out somewhat similar to the finale of the movie — Mjolnir saps the life out of her and Jane willingly decides to use the hammer one last time to save humanity. But in the comics, Thor, so devastated by Janes’ death, enlists Odin (who is still alive) to resurrect her.

This is where “Love and Thunder” does its best to upend tropes like those seen in “Shazam!” Every time Jane uses the hammer, it literally sucks the power and life out of her. Her rampant desire to live by any means necessary ends up backfiring and forces her to confront the choices she’s made in her life.

“Iron Man”

The MCU hasn’t specifically dabbled in telling stories of disabled characters, at least when they’re heroes. Tony Stark’s (Robert Downey Jr.) heart problems were at the center of the first “Iron Man” feature, another example of a magical cure storyline, though it’s not presented as a specifically disabled storyline. Tony never really examines his own mortality or his privilege in being able to literally create a new heart, it’s simply something he accomplishes and moves on from. His close pal, James Rhodes (Don Cheadle) is paralyzed during a key “Civil War” battle, but audiences likely won’t remember that, considering the subsequent movies have barely addressed it. Like Stark, Rhodes gets a magical exoskeleton, turning him into War Machine, that allows him to walk. Problem solved!

The only time a disabled storyline has been the focus, outside of “Love and Thunder” is in the 2018 feature, “Ant-Man and the Wasp.” In that feature, the narrative’s villain, Ava (Hannah John-Kamen) has chronic pain and is determined to stop it by any means necessary. It’s more of a return to the world of “Unbreakable,” where villainy tends to go hand-in-hand with disability. Heroes are able to remove their disabilities entirely with tech, while villains become consumed by the bitterness and suffering their disability evokes.

It’s another reason “Love and Thunder” seems to at least try to undermine that mentality. Jane is angry at her diagnosis, but refuses to wallow. She wants to leave a legacy. The tech helps, but only for a moment.

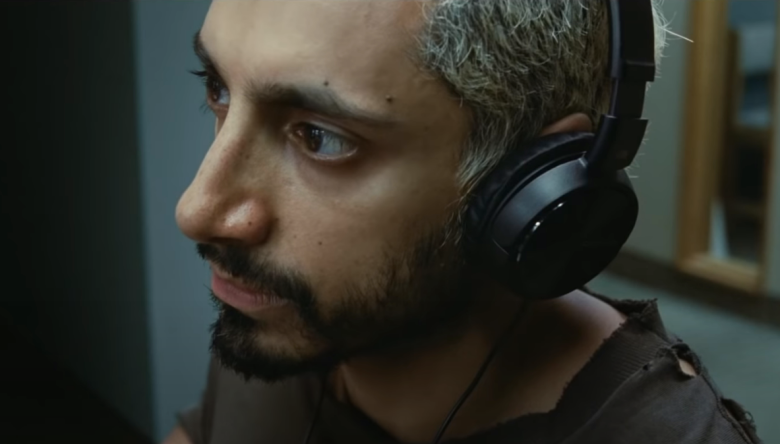

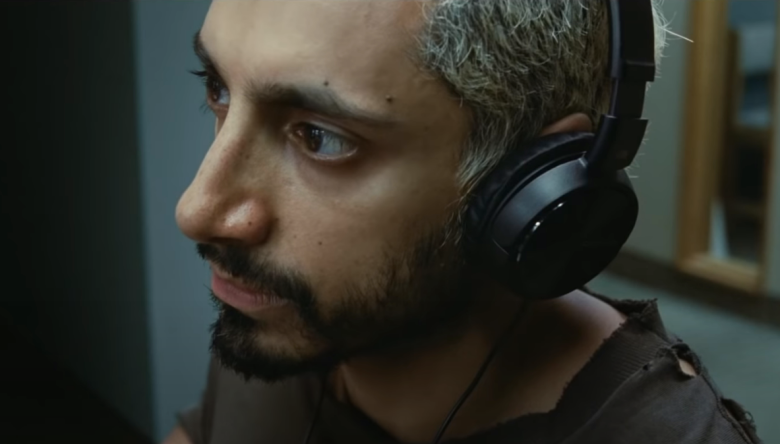

The best recent cinematic comparison then isn’t from another superhero movie, it’s with the lauded 2019 feature “Sound of Metal,” as the film follows Ruben (played by Riz Ahmed), a heavy metal drummer who believes that a cochlear implant will magically fix his deafness. Much like “Love and Thunder,” nothing is “fixed” in “Sound of Metal.” Even after the implant, Ruben must adapt and navigate the world with a new device that will give him as comfortable a life as he’s willing to make for himself.

“Sound of Metal”

Amazon

Sure, there’s a heavy preponderance in film and television to use disabled characters and their deaths as a tactic to remind audiences to “live your life because at any minute the horrors of disability, which always equals death, can happen anytime.” (See the likes of “Me Before You” or “Million Dollar Baby” for examples. Or, better yet, don’t.)

But in the case of “Love and Thunder,” the onus is always on Jane to figure out how to make the most of her current life. When she decides to keep using the hammer, knowing it will kill her, the decision has nothing to do with Thor, but her own desire to be a hero.

Jane is allowed to go out on her terms. She uses the hammer to destroy Gorr the God Butcher (Christian Bale) and has a teary goodbye with Thor. It’s a common disability trope — if you’ve gotta die, might as well resolve all your unfinished business and go out on a high note — but the fact that Jane does die feels subversive in its own way, because her death isn’t designed as a deus ex machina. She’s gone, but she did it the way she wanted to. Deaths don’t often stick in Disney movies, but not having Mjolnir come back in the eleventh hour or finding some Asgardian trickery to cure Jane, is oddly refreshing.

“Thor: Love and Thunder” isn’t going to be a disabled story for the ages. Many might not see even see Jane’s cancer as a disability. Some might see it as a gimmick merely to manipulate tears (again, in the world of disability tropes, that’s valid). But when the notion of being a superhero is often used to erase disability, “Love and Thunder” doesn’t subscribe to that. It’s got something more powerful on its mind.

A Disney release, “Thor: Love and Thunder” is now in theaters.

Superhero films have a long, fraught history with the depiction of disability. Often, these films’ disabled characters are portrayed as villains, like Dr. Poison in “Wonder Woman” or Samuel L. Jackson’s Elijah Price in “Unbreakable.” Most, like DC’s Doctor Mid-Nite, haven’t yet been considered worthy of bringing into the cinematic world. And when these characters do appear in sprawling movie and TV franchises, they are often played by non-disabled actors (such is the case with “Daredevil” or Professor X in “X-Men.”)

There’s no dearth of these kinds of heroes and villains in comic books: Disabled superheroes have been around since the 1940s, with Doctor Mid-Nite — who can see in the dark but is blind at night — widely considered the first disabled superhero. Others include Oracle, otherwise known as Barbara Gordon, who became the hero after being paralyzed; the inventive Komodo, a double amputee who has the power to regrow limbs; and the Hornet, who has cerebral palsy.

But while superhero stories reign supreme at the box office and beyond, translating this wide variety of disabled superheroes to screens both large and small has been frustratingly delayed.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has certainly tried its hand at touching on disability in their features, though with about as much success and nuance as its portrayal of LGBTQ characters. Taika Waititi’s latest entry in the “Thor” series won’t rewrite the book on disability portrayals in Marvel movies, but the film’s treatment of Dr. Jane Foster (Natalie Portman) as the Mighty Thor offers some compelling new ideas.

“Thor: Love and Thunder”

Jasin Boland

“Love and Thunder” condenses a lot of Jane’s cancer journey from the comics. Jane was diagnosed with cancer in the comics in 2012, losing her own mother to the disease first, as also depicted in the film. In the comics, Jane initially refuses any magical help from Thor, and his mighty hammer Mjolnir reaches out to her through a telepathic link between the two, as opposed to Waititi’s film, in which a flashback shows Thor commanding Mjolnir to protect Jane. In both the film and comic storyline, once Jane picks up Mjolnir, she becomes the Mighty Thor (though, in the comics, it takes Thor a bit longer to figure out his ex is under the helmet).

Jane’s predominant aim in Waititi’s feature is to help a lost Thor (Chris Hemsworth) realize he does want family, love, and community in his life, but her own narrative feels far closer to a conflicted disabled story, as she struggles to deal with her cancer diagnosis.

In other superhero movies — including those created by both Marvel and DC — Jane’s cancer would easily be cured by the implementation and utilization of superpowers. Such is the case with the 2019 feature “Shazam!” and the character of Freddy Freeman (Jack Dylan Grazier). Freeman is the best friend of the title character, AKA Billy Batson (played by Asher Angel), who uses a crutch due to an unexplained disability.

There’s a lot to praise about Freddy, especially as much of the film’s humor is centered around poking fun at how able-bodied people look at disabled people. (When wise-cracking Freddy first meets Billy he describes himself as a “disabled foster kid” who, presumably, should “have it all.”)

“Shazam!”

Warner Bros.

But in the film’s third act, when Billy needs his foster family to help him, and the magical powers of Shazam are shared between the other foster children, Freddy “reaches his full potential” by becoming a grown-up — and able-bodied — character played by Adam Brody. “Shazam!” ends before we see Freddy grapple with this newfound “cure,” but the idea that to reach one’s “full potential,” they will be non-disabled stings and relies on outdated ideas that having a disability is something that, ultimately, should — and could — be cured.

“Love and Thunder” is often a stark exploration of religion and death, and much of what fuels Jane is her desire to live. She doesn’t feel she’s done with the work she’s pioneered (both in science and, later, as the Mighty Thor) and is willing to take any cure presented to her.

In this case, the power of Thor’s broken hammer, Mjolnir, is (at least temporarily) that cure for her. Jane pieces it back together and becomes the buff, blonde Mighty Thor. Problem solved, right? But when Jane picks up Mjolnir and becomes Mighty Thor, her sudden superhero powers aren’t framed as any sort of cure-all. It’s a temporary stop-gap, a badass and supercharged example of durable medical equipment.

It won’t “fix” anything, only delay her illness and help Jane live the rest of her life in a literally more powerful manner. Interestingly, in the comics Jane’s demise plays out somewhat similar to the finale of the movie — Mjolnir saps the life out of her and Jane willingly decides to use the hammer one last time to save humanity. But in the comics, Thor, so devastated by Janes’ death, enlists Odin (who is still alive) to resurrect her.

This is where “Love and Thunder” does its best to upend tropes like those seen in “Shazam!” Every time Jane uses the hammer, it literally sucks the power and life out of her. Her rampant desire to live by any means necessary ends up backfiring and forces her to confront the choices she’s made in her life.

“Iron Man”

The MCU hasn’t specifically dabbled in telling stories of disabled characters, at least when they’re heroes. Tony Stark’s (Robert Downey Jr.) heart problems were at the center of the first “Iron Man” feature, another example of a magical cure storyline, though it’s not presented as a specifically disabled storyline. Tony never really examines his own mortality or his privilege in being able to literally create a new heart, it’s simply something he accomplishes and moves on from. His close pal, James Rhodes (Don Cheadle) is paralyzed during a key “Civil War” battle, but audiences likely won’t remember that, considering the subsequent movies have barely addressed it. Like Stark, Rhodes gets a magical exoskeleton, turning him into War Machine, that allows him to walk. Problem solved!

The only time a disabled storyline has been the focus, outside of “Love and Thunder” is in the 2018 feature, “Ant-Man and the Wasp.” In that feature, the narrative’s villain, Ava (Hannah John-Kamen) has chronic pain and is determined to stop it by any means necessary. It’s more of a return to the world of “Unbreakable,” where villainy tends to go hand-in-hand with disability. Heroes are able to remove their disabilities entirely with tech, while villains become consumed by the bitterness and suffering their disability evokes.

It’s another reason “Love and Thunder” seems to at least try to undermine that mentality. Jane is angry at her diagnosis, but refuses to wallow. She wants to leave a legacy. The tech helps, but only for a moment.

The best recent cinematic comparison then isn’t from another superhero movie, it’s with the lauded 2019 feature “Sound of Metal,” as the film follows Ruben (played by Riz Ahmed), a heavy metal drummer who believes that a cochlear implant will magically fix his deafness. Much like “Love and Thunder,” nothing is “fixed” in “Sound of Metal.” Even after the implant, Ruben must adapt and navigate the world with a new device that will give him as comfortable a life as he’s willing to make for himself.

“Sound of Metal”

Amazon

Sure, there’s a heavy preponderance in film and television to use disabled characters and their deaths as a tactic to remind audiences to “live your life because at any minute the horrors of disability, which always equals death, can happen anytime.” (See the likes of “Me Before You” or “Million Dollar Baby” for examples. Or, better yet, don’t.)

But in the case of “Love and Thunder,” the onus is always on Jane to figure out how to make the most of her current life. When she decides to keep using the hammer, knowing it will kill her, the decision has nothing to do with Thor, but her own desire to be a hero.

Jane is allowed to go out on her terms. She uses the hammer to destroy Gorr the God Butcher (Christian Bale) and has a teary goodbye with Thor. It’s a common disability trope — if you’ve gotta die, might as well resolve all your unfinished business and go out on a high note — but the fact that Jane does die feels subversive in its own way, because her death isn’t designed as a deus ex machina. She’s gone, but she did it the way she wanted to. Deaths don’t often stick in Disney movies, but not having Mjolnir come back in the eleventh hour or finding some Asgardian trickery to cure Jane, is oddly refreshing.

“Thor: Love and Thunder” isn’t going to be a disabled story for the ages. Many might not see even see Jane’s cancer as a disability. Some might see it as a gimmick merely to manipulate tears (again, in the world of disability tropes, that’s valid). But when the notion of being a superhero is often used to erase disability, “Love and Thunder” doesn’t subscribe to that. It’s got something more powerful on its mind.

A Disney release, “Thor: Love and Thunder” is now in theaters.