By most industry standards, “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” is a massive success. Released at a time when theatrical studio movies have underserved the market for family-friendly entertainment, it transforms the most popular family-friendly videogame franchise into a blockbuster hit.

Enlivened by the same cartoonish pizazz that Illumination Entertainment brought to the “Despicable Me” franchise, the new movie finally cracks an elusive code for Nintendo, which has guarded its library for decades in the aftermath of the misbegotten 1993 live action “Mario” movie. And there’s definitely more to come: With its record-breaking $195 million gross across five days, “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” sets the stage for a whole new era of Nintendo adaptations.

There’s only one problem: “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” is abysmal, at least to my eyes.

I know, the saga of a wayward Brooklyn plumber and his faithful brother, as they get sucked into the Mushroom Kingdom to take down petty dragon Bowser, doesn’t aim for high art — but it’s nevertheless disconcerting to witness such a sleek corporate product not even try to muster some semblance of depth. Instead, it defers to the brainless logic of the games — the running, jumping, hit-the-golden-question-block kind — while Matthew Fogel’s workmanlike script fills in the gaps with breezy, forgettable dialogue throughout.

I sat through a screening earlier this week aghast at the dissolution of narrative standards at hand. At 90 minutes, it’s not a tough sit, but it’s also not exactly a movie so much as a feature-length Twitch stream of in-game cutscenes. Say what you want about that ’93 disaster; at least it swung for the fences. “The Super Marios Brothers Movie,” on the other hand, panders to expectations with such abject laziness that it left me disowning my own nostalgia for the early games and wondering if all of us young button-mashers laid the groundwork for the death of cinema by feeding the demand for this empty product over the years.

The most dispiriting aspect of my screening experience stemmed from the ebullient eight-year-olds sitting behind me, who blurted out every game-related Easter egg and chortled at the mindless gameplay-as-movie routine pretty much the whole way through. It hit all their buttons without the slightest effort to challenge or enlighten them in the process; it also left me, an optimist who searches for the potential of movies to thrive wherever they can, wondering if the next generation would rather watch them burn.

It might seem odd, in a weekend column that tends to deal with the challenges and opportunities of the independent realm, to devote any space at all to a vapid IP grab with bottom-line motives apparent to any conscious person. But as I often ponder the path that talented writers and directors follow into the studio system, I’m left wondering how they might stand to improve a facet of the market that could use their strengths. Nintendo needs to hire better filmmakers for its new blockbuster business — and more of them should seek out family-friendly gigs.

When filmmakers work their way into the studio system after making strong work on a smaller scale, they often wind up with gigs aimed at more mature audiences, from the Marvel and Star Wars universes to horror franchises like “Scream.” Some of these opportunities may lead to solid work. But filmmakers with agents helping them navigate their options shouldn’t pass up the chance to consider how they might contribute to the family-friendly realm — and elevate its quality in the process.

“Pete’s Dragon”

One of the few directors in recent years who actually mined productive results on this path is David Lowery. After his poetic crime saga “Ain’t Them Bodies Saints,” Lowery parlayed his ethereal narrative style into a writing gig for a live-action remake of “Pete’s Dragon” that he ended up directing as well. The result was a wondrous, textured reimagining of the 1977 movie that doubles as a meditation on loss and resurrects the Spielbergian sense of awe that many Spielberg movies lack. It’s a haunting folk tale that still delivers on expectations of a creature feature with thrills to spare. Lowery didn’t have to give up on his more adult undertaking to make it, either: “Pete’s Dragon” was followed by the remarkable microbudget metaphysical epic “A Ghost Story,” the Robert Redford heist romance “”The Old Man & the Gun,” and his visually astounding Arthurian riff “The Green Knight.”

Over the past year, Lowery has doubled back to the family-friendly arena with “Peter Pan & Wendy,” which Disney releases on April 29, and that’s enough reason for even people who checked out on all things Peter Pan decades ago to pay attention.

Why does Lowery keep coming back to the arena of commercial kids’ entertainment with such gusto — and does he see potential for more filmmakers to explore the same path?

Looking for some way to clear my head after “The Super Mario Bros. Movie,” I tracked Lowery down by phone this week to Germany, where he’s in pre-production on the A24-produced “Mother Mary,” a so-called “epic pop melodrama” starring Anne Hathaway and Michaela Cole. I’ve talked to Lowery a lot over the years and always found him to be a sobering voice when it comes to questions of how to navigate the industry with a singular creative voice. He took a break from a series of meetings to chat with me about his specific journey into the producing meaningful entertainment for younger viewers, and why it has never felt like a compromise. I hope his perspective inspires more filmmakers to storm the gates of Nintendo and other family-friendly IP factories, because those eight-year-olds sitting behind me deserve better, whether or not they realize it.

IndieWire: Your work outside of Disney can be pretty dark and mature. Why did the challenge of writing family-friendly movies appeal to you?

DAVID LOWERY: I approach all of my storytelling from two points, one of naivety and the other from a sense of emotional maturity. I think that children certainly have both. To a certain extent, I still do. I approach the world from a very naive perspective, but the emotions the world elicits in me have always had a gravity that hasn’t changed. I remember feeling as a child all these emotions I still feel as an adult and I don’t process them differently now.

Is it any less creatively satisfying to make movies for younger audiences?

When I’m writing a film for an adult or a child audience I’m always approaching them from a similar perspective. The differences come from other areas. The things that make a film skew more towards adults or family aren’t so much in terms of tone or perspective, but in the feelings you put on yourself or that you take off an individual project. I know that a Disney movie needs to appeal more to a wider audience than something like “The Green Knight” or “A Ghost Story.” But I approach them from an intellectual perspective from the same level. They’re just asking different things.

Still, the studio knows that it needs certain superficial aspects to appeal to its viewers — bright colors, an easy-to-follow storyline, etc. How do you innovate within those boundaries?

We’ve all seen movies that have those attributes that are terrible. There’s a tendency to attribute the negative demands of the movie to something that has the lowest common denominator. But sometimes those things are good. Simplicity is very important for a family film. You don’t want to have to get too caught up in plot and world building. For a younger audience, you want the narrative to have elegance and simplicity that allows all of the emotions to rise to the forefront.

Beyond your own work, do any movies come to mind that do this well?

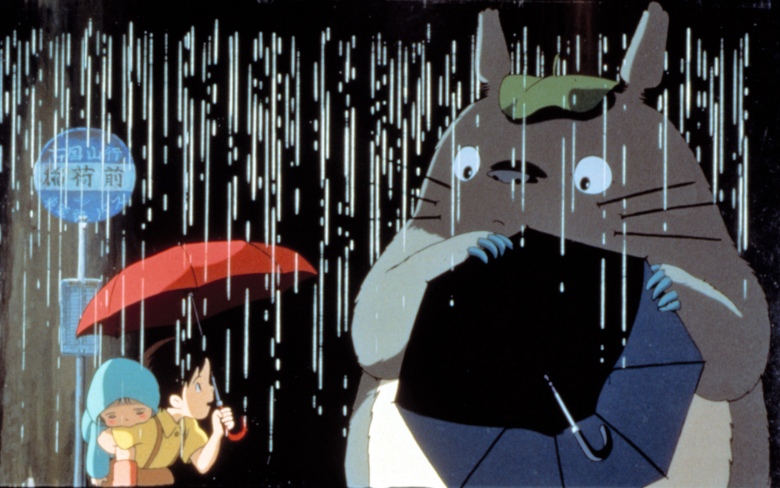

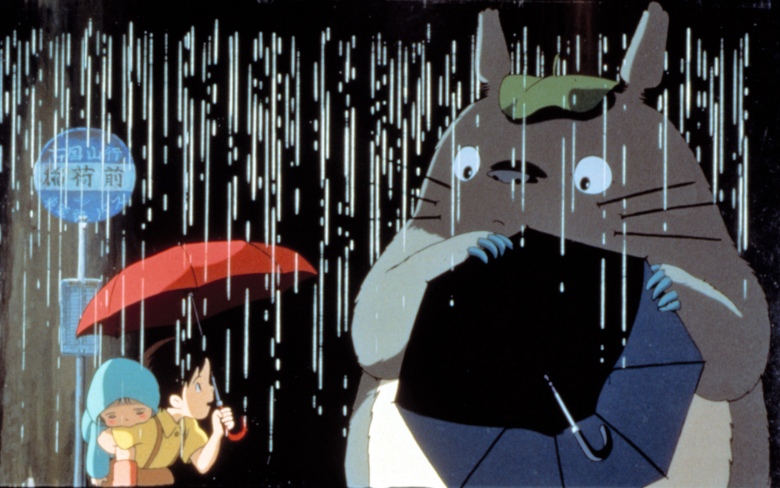

I think back to Miyazaki and “My Neighbor Totoro” a lot. I know it’s easy to point to that movie, and I couldn’t make a movie that functions like that at a U.S. studio. It just wouldn’t work. It’s an auteur film. But you can still use that as a standard for how simple and basic a piece of storytelling can get. Simplicity can be an incredibly valuable thing. It’s a doorway into an incredibly rich emotional experience.

“My Neighbor Totoro”

©50th Street Films/Courtesy Everett Collection

How do you feel when you see a bad family-friend movie?

Frankly, we all know nobody sets out to make a bad movie. Sometimes things just go awry. There’s always the fear that will happen. It’s never anyone’s fault. It’s never a case of someone being antagonistic toward a director. There are mixed intentions.

What keeps you coming back to this challenge?

With “Pete’s Dragon,” I think we achieved something very special. With Peter Pan the target was completely different. It has a different value for the studio. We were starting over from scratch. If I didn’t think it was worth taking the risk I wouldn’t try it again. It’s a sincere expression of something that is emotionally resonant for me but I know it will be seen by more people and could even be a formative experience for some of them. When you think back on the movies that have made the biggest impression on you in your life, so much of them are from when you’re young. For all the risks involved when you’re a creative, sensitive person and make a giant studio movie, it is worth it, because you can get something on screen that could make a valuable impression on an audience member just beginning their journey through life. That’s why I make these movies and I will seek to keep making them. It’s contributes more to the world than just giving something to me. It gives something to a future generation.

Why would you encourage more filmmakers to look for these types of projects?

Very often when you’re an independent filmmaker, you’re dead broke, so writing opportunities are wonderful. One should pursue them. I was hired to write “Pete’s Dragon.” The directing came later. It was through the writing process that I realized how wonderful this type of storytelling could be and how much it was in sync with what my storytelling instincts were. If you’re a filmmaker who sees an opportunity to tell a story in a video game that can ignite that same spark in someone’s generation, there’s no reason not to pursue that.

Are there certain projects you definitely won’t consider in this arena?

I remember when there were reports about a trilogy of “Tetris” movies and thinking, “I don’t see it.” I have my own tastes, but I never say no to anything outright, and I’ll always consider an idea. I think there’s potential in everything. Mike White wrote “The Emoji Movie” and probably did a good job. OK, I didn’t see it, but I was interested when I realized he was involved. I love that Dean Fleischer Camp is following up “Marcel the Shell” with “Lilo & Stitch.” It’s an honorable thing to do. It’s not selling out.

Do you think studios have an obligation to make substantial entertainment for younger audiences?

When I was little, I was obsessed with “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II.” To me, it was so much better than the first one. They were fighting with pizzas and salamis. I thought it was hilarious. Now, looking at it from an adult perspective, I know that it’s inarguably not as good. Realizing that made me less precious about everything. Sometimes kids just want to laugh. It doesn’t matter to them that it’s less emotionally substantive. But I also know now that the first was so heavy and emotional, which probably did me a lot of good.

Not every movie is going to be “My Neighbor Totoro” or “E.T.” There are all sorts of reasons why. But just having the ambition to get there is still giving family audiences something of value, something nourishing. My aspiration to make films that function in that way supersedes any frustrations I might have en route to making them. Until this industry leaves me a bitter shell, those ideas still compel me to want to tell these stories.

As usual, I encourage reader feedback to this column via email: eric@indiewire.com

Check out earlier columns here.

Enlivened by the same cartoonish pizazz that Illumination Entertainment brought to the “Despicable Me” franchise, the new movie finally cracks an elusive code for Nintendo, which has guarded its library for decades in the aftermath of the misbegotten 1993 live action “Mario” movie. And there’s definitely more to come: With its record-breaking $195 million gross across five days, “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” sets the stage for a whole new era of Nintendo adaptations.

There’s only one problem: “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” is abysmal, at least to my eyes.

I know, the saga of a wayward Brooklyn plumber and his faithful brother, as they get sucked into the Mushroom Kingdom to take down petty dragon Bowser, doesn’t aim for high art — but it’s nevertheless disconcerting to witness such a sleek corporate product not even try to muster some semblance of depth. Instead, it defers to the brainless logic of the games — the running, jumping, hit-the-golden-question-block kind — while Matthew Fogel’s workmanlike script fills in the gaps with breezy, forgettable dialogue throughout.

I sat through a screening earlier this week aghast at the dissolution of narrative standards at hand. At 90 minutes, it’s not a tough sit, but it’s also not exactly a movie so much as a feature-length Twitch stream of in-game cutscenes. Say what you want about that ’93 disaster; at least it swung for the fences. “The Super Marios Brothers Movie,” on the other hand, panders to expectations with such abject laziness that it left me disowning my own nostalgia for the early games and wondering if all of us young button-mashers laid the groundwork for the death of cinema by feeding the demand for this empty product over the years.

The most dispiriting aspect of my screening experience stemmed from the ebullient eight-year-olds sitting behind me, who blurted out every game-related Easter egg and chortled at the mindless gameplay-as-movie routine pretty much the whole way through. It hit all their buttons without the slightest effort to challenge or enlighten them in the process; it also left me, an optimist who searches for the potential of movies to thrive wherever they can, wondering if the next generation would rather watch them burn.

It might seem odd, in a weekend column that tends to deal with the challenges and opportunities of the independent realm, to devote any space at all to a vapid IP grab with bottom-line motives apparent to any conscious person. But as I often ponder the path that talented writers and directors follow into the studio system, I’m left wondering how they might stand to improve a facet of the market that could use their strengths. Nintendo needs to hire better filmmakers for its new blockbuster business — and more of them should seek out family-friendly gigs.

When filmmakers work their way into the studio system after making strong work on a smaller scale, they often wind up with gigs aimed at more mature audiences, from the Marvel and Star Wars universes to horror franchises like “Scream.” Some of these opportunities may lead to solid work. But filmmakers with agents helping them navigate their options shouldn’t pass up the chance to consider how they might contribute to the family-friendly realm — and elevate its quality in the process.

“Pete’s Dragon”

One of the few directors in recent years who actually mined productive results on this path is David Lowery. After his poetic crime saga “Ain’t Them Bodies Saints,” Lowery parlayed his ethereal narrative style into a writing gig for a live-action remake of “Pete’s Dragon” that he ended up directing as well. The result was a wondrous, textured reimagining of the 1977 movie that doubles as a meditation on loss and resurrects the Spielbergian sense of awe that many Spielberg movies lack. It’s a haunting folk tale that still delivers on expectations of a creature feature with thrills to spare. Lowery didn’t have to give up on his more adult undertaking to make it, either: “Pete’s Dragon” was followed by the remarkable microbudget metaphysical epic “A Ghost Story,” the Robert Redford heist romance “”The Old Man & the Gun,” and his visually astounding Arthurian riff “The Green Knight.”

Over the past year, Lowery has doubled back to the family-friendly arena with “Peter Pan & Wendy,” which Disney releases on April 29, and that’s enough reason for even people who checked out on all things Peter Pan decades ago to pay attention.

Why does Lowery keep coming back to the arena of commercial kids’ entertainment with such gusto — and does he see potential for more filmmakers to explore the same path?

Looking for some way to clear my head after “The Super Mario Bros. Movie,” I tracked Lowery down by phone this week to Germany, where he’s in pre-production on the A24-produced “Mother Mary,” a so-called “epic pop melodrama” starring Anne Hathaway and Michaela Cole. I’ve talked to Lowery a lot over the years and always found him to be a sobering voice when it comes to questions of how to navigate the industry with a singular creative voice. He took a break from a series of meetings to chat with me about his specific journey into the producing meaningful entertainment for younger viewers, and why it has never felt like a compromise. I hope his perspective inspires more filmmakers to storm the gates of Nintendo and other family-friendly IP factories, because those eight-year-olds sitting behind me deserve better, whether or not they realize it.

IndieWire: Your work outside of Disney can be pretty dark and mature. Why did the challenge of writing family-friendly movies appeal to you?

DAVID LOWERY: I approach all of my storytelling from two points, one of naivety and the other from a sense of emotional maturity. I think that children certainly have both. To a certain extent, I still do. I approach the world from a very naive perspective, but the emotions the world elicits in me have always had a gravity that hasn’t changed. I remember feeling as a child all these emotions I still feel as an adult and I don’t process them differently now.

Is it any less creatively satisfying to make movies for younger audiences?

When I’m writing a film for an adult or a child audience I’m always approaching them from a similar perspective. The differences come from other areas. The things that make a film skew more towards adults or family aren’t so much in terms of tone or perspective, but in the feelings you put on yourself or that you take off an individual project. I know that a Disney movie needs to appeal more to a wider audience than something like “The Green Knight” or “A Ghost Story.” But I approach them from an intellectual perspective from the same level. They’re just asking different things.

Still, the studio knows that it needs certain superficial aspects to appeal to its viewers — bright colors, an easy-to-follow storyline, etc. How do you innovate within those boundaries?

We’ve all seen movies that have those attributes that are terrible. There’s a tendency to attribute the negative demands of the movie to something that has the lowest common denominator. But sometimes those things are good. Simplicity is very important for a family film. You don’t want to have to get too caught up in plot and world building. For a younger audience, you want the narrative to have elegance and simplicity that allows all of the emotions to rise to the forefront.

Beyond your own work, do any movies come to mind that do this well?

I think back to Miyazaki and “My Neighbor Totoro” a lot. I know it’s easy to point to that movie, and I couldn’t make a movie that functions like that at a U.S. studio. It just wouldn’t work. It’s an auteur film. But you can still use that as a standard for how simple and basic a piece of storytelling can get. Simplicity can be an incredibly valuable thing. It’s a doorway into an incredibly rich emotional experience.

“My Neighbor Totoro”

©50th Street Films/Courtesy Everett Collection

How do you feel when you see a bad family-friend movie?

Frankly, we all know nobody sets out to make a bad movie. Sometimes things just go awry. There’s always the fear that will happen. It’s never anyone’s fault. It’s never a case of someone being antagonistic toward a director. There are mixed intentions.

What keeps you coming back to this challenge?

With “Pete’s Dragon,” I think we achieved something very special. With Peter Pan the target was completely different. It has a different value for the studio. We were starting over from scratch. If I didn’t think it was worth taking the risk I wouldn’t try it again. It’s a sincere expression of something that is emotionally resonant for me but I know it will be seen by more people and could even be a formative experience for some of them. When you think back on the movies that have made the biggest impression on you in your life, so much of them are from when you’re young. For all the risks involved when you’re a creative, sensitive person and make a giant studio movie, it is worth it, because you can get something on screen that could make a valuable impression on an audience member just beginning their journey through life. That’s why I make these movies and I will seek to keep making them. It’s contributes more to the world than just giving something to me. It gives something to a future generation.

Why would you encourage more filmmakers to look for these types of projects?

Very often when you’re an independent filmmaker, you’re dead broke, so writing opportunities are wonderful. One should pursue them. I was hired to write “Pete’s Dragon.” The directing came later. It was through the writing process that I realized how wonderful this type of storytelling could be and how much it was in sync with what my storytelling instincts were. If you’re a filmmaker who sees an opportunity to tell a story in a video game that can ignite that same spark in someone’s generation, there’s no reason not to pursue that.

Are there certain projects you definitely won’t consider in this arena?

I remember when there were reports about a trilogy of “Tetris” movies and thinking, “I don’t see it.” I have my own tastes, but I never say no to anything outright, and I’ll always consider an idea. I think there’s potential in everything. Mike White wrote “The Emoji Movie” and probably did a good job. OK, I didn’t see it, but I was interested when I realized he was involved. I love that Dean Fleischer Camp is following up “Marcel the Shell” with “Lilo & Stitch.” It’s an honorable thing to do. It’s not selling out.

Do you think studios have an obligation to make substantial entertainment for younger audiences?

When I was little, I was obsessed with “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II.” To me, it was so much better than the first one. They were fighting with pizzas and salamis. I thought it was hilarious. Now, looking at it from an adult perspective, I know that it’s inarguably not as good. Realizing that made me less precious about everything. Sometimes kids just want to laugh. It doesn’t matter to them that it’s less emotionally substantive. But I also know now that the first was so heavy and emotional, which probably did me a lot of good.

Not every movie is going to be “My Neighbor Totoro” or “E.T.” There are all sorts of reasons why. But just having the ambition to get there is still giving family audiences something of value, something nourishing. My aspiration to make films that function in that way supersedes any frustrations I might have en route to making them. Until this industry leaves me a bitter shell, those ideas still compel me to want to tell these stories.

As usual, I encourage reader feedback to this column via email: eric@indiewire.com

Check out earlier columns here.