Living as an ex-pat in Paris in the late 1950s, Melvin Van Peebles taught himself the language and wrote five books in French. The fifth, 1967’s “La Permission,” became the basis for his 1968 feature-film debut, “The Story of a Three-Day Pass.” A commentary on France’s contradictory attitudes about race, it’s an exploration of an interracial relationship between a Black American GI stationed in France (Turner, played by Harry Baird) and a white Parisian woman (Miriam, played by Nicole Berger). A 4K restoration by IndieCollect, in consultation with his son Mario Van Peebles, opened in US theaters May 14.

The re-release isn’t tied to a milestone anniversary. “There’s a renewed interest in looking at Black history, given all that’s happened in the last few years, and you see it on the screen,” Mario said. “It’s also an anniversary of all things Van Peebles in a way: ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song’ celebrates its 50-year anniversary this year. And then, weirdly enough, 20 years later, I did ‘New Jack City’ in 1991. So, our anniversaries overlap — 30 years for me and 50 for dad. I think he did a lot of things that were ahead of their time, and people are still discovering the work decades later.”

The elder Van Peebles will be 89 on August 21. Overseeing his estate are Mario and his brother Max, who might recognize an urgency in collaborating with their father to reintroduce his life’s work. As the “godfather of independent Black cinema,” he’s an artist who may not have gotten his due. Mario said that boxing legend Muhammad Ali told him as much.

“He said, ‘I don’t think people recognize what your father did, when he put Black power on the screen. I put it on in the ring. He put it on the screen’,” Mario said. “But then Paul Robeson also asked, ‘When you buy into the paradigm and values of the people who would buy and sell you, what have you become?’ So how hungry are we for the dominant culture to acknowledge us? Melvin Van Peebles never thought, ‘My reward is going to be people acknowledging me, let alone people who are cultural trespassers.”

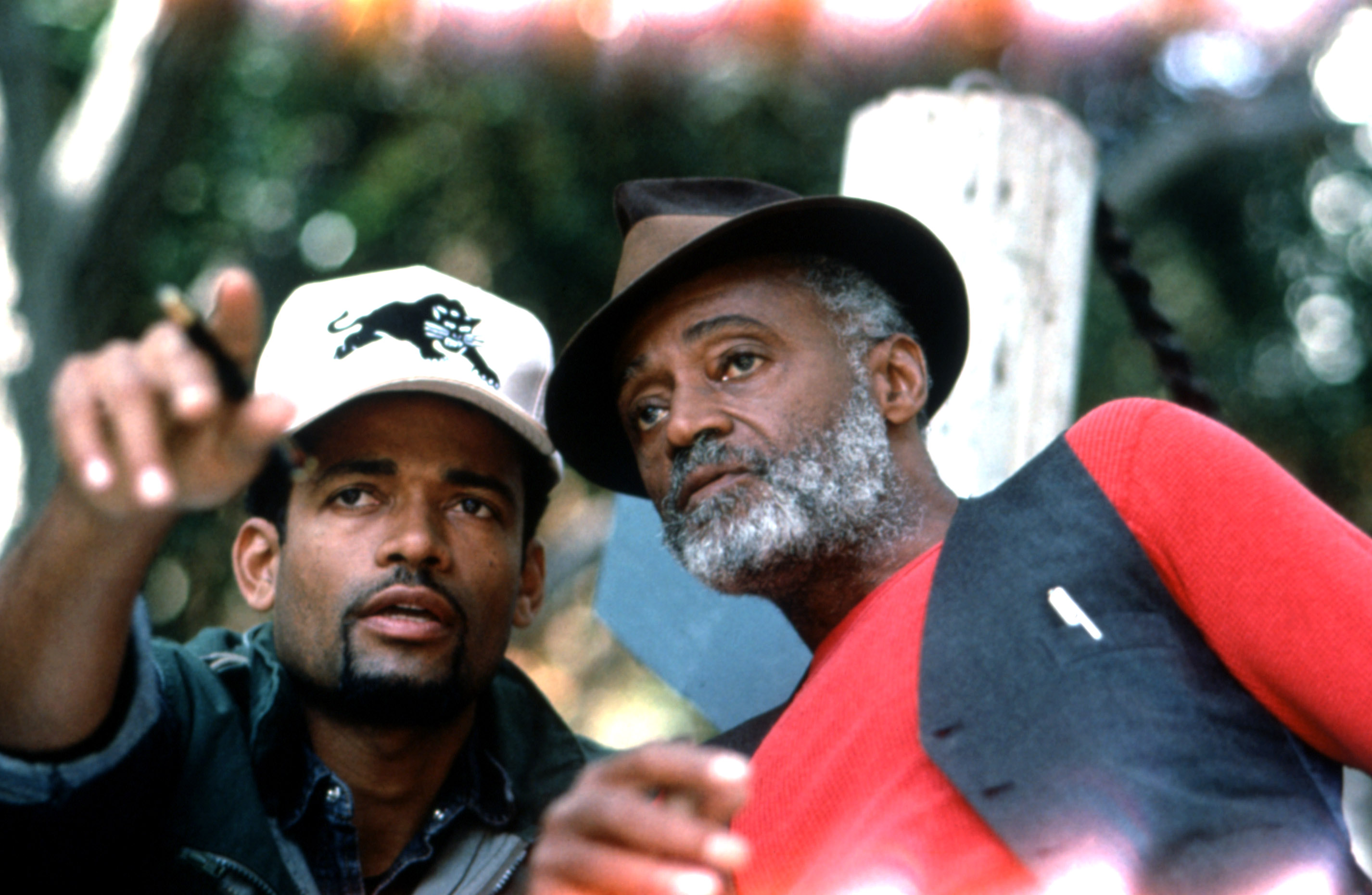

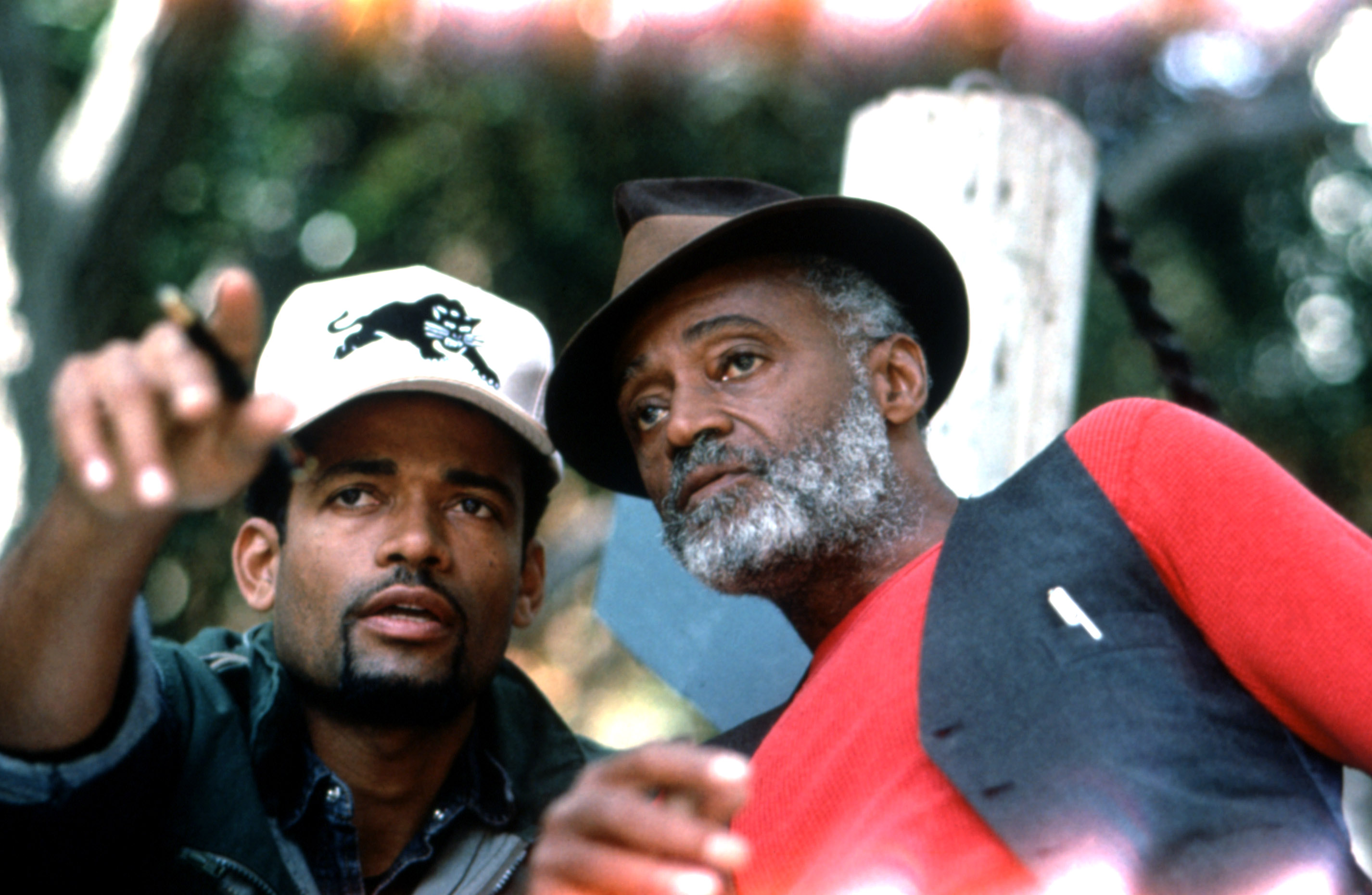

“Panther,” director Mario Van Peebles with father/writer Melvin Van Peebles on set, 1995.

GramercyPictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

By contrast, he recalled the satisfaction that came when his father was stopped in the street by a fan. “We were going for a stroll, and this brother came up to us with his family and said, ‘Excuse me, Mr. Van Peebles. I’ve got my son, my daughter, and my wife here, and I just wanted to say thank you. Sometimes I go to the movies and I’m entertained. Sometimes I learn something new. Sometimes I’m compelled to think. And sometimes I come out proud to be a man of color. With your movies, I get all of the above’. Now, that’s the reward,” Mario said.

With “Three-Day Pass,” Peebles didn’t set out to make a radical film. It’s a boy-meets-girl with a twist: the romance is interracial, which was very much a screen taboo at the time of its release — one year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia.

“Three-Day Pass” also subverted Hollywood interracial love stories like “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” a year prior, starring Sidney Poitier. Unlike the insufferably tame “Dinner,” Turner and Miriam dance intimately, drink, frolic on the beach, and even have sex. In 1968 America, that was gutsy filmmaking.

“He wasn’t at all interested in appealing to white people for his humanity, nor was he interested in making a movie about an upstanding ‘colored’ guy,” Mario said. “Turner is a regular dude, imperfect, trying to meet a girl, trying to get laid, trying to fall in love, trying to enjoy his life, like most men. So at a time when others were striving to be aspirational in terms of depicting Black people, Dad was just saying, ‘Yeah, that’s cool, but in my film, we’ll just have two everyday folks, who are trying to figure it out’. I remember him talking about getting to a place where we, as Black people, have the right to be ordinary.”

Before “Three-Day Pass,” there hadn’t been quite a film like it made by a Black filmmaker, with such freewheeling spontaneity. The few studio films that featured Black characters were often based on white liberal fantasies that fulfilled notions about what a “good Negro” should be. The Black lead was typically male and neutered — figuratively, of course.

Van Peebles shattered that illusion with films like “Three-Day Pass” and the incendiary “Sweet Sweetback” three years later. It became a reference point for radical, subversive Black cinema at a time when Black Americans were primed for it, post-Civil Rights movement.

“Dr. King was saying, ‘We must have freedom by peaceful means’, and brother Malcolm saying, ‘We must have freedom by any means’, and when America killed them both, Black folks got tired of being ‘colored’ and said, ‘Fuck that, we’re Black’,” Mario said. “And the subtext of ‘Black’ was, we were not trying to fit in, we were saying Black is beautiful, and we were going to have the Black Panther Party for self defense, and embrace the Black power mantra. And with all that in mind, it gave a whole different perspective on ‘Three-Day Pass’. Then, he came back with ‘Sweetback’ and put the idea of revolution on the screen for the first time.”

Van Peebles’ own story motivated him to pick up a camera. “It’s a film that, to some degree, must’ve been inspired by my parents’ relationship, in that I’m the product of said union,” Mario said. “Like Turner, he was in the service, in the Air Force, when he met my mom, who is white, in France, just like Turner and Miriam, and fell in love.

Often described as “New Wave-inspired,” star Nicole Berger previously appeared in short films by New Wave pioneers Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer, and co-starred in François Truffaut’s 1960 “Shoot the Piano Player.” Mario gives more credit to his father’s ingenuity and whim.

“He’s always had his own vibe and he took cinematic chances,” Mario said. “He had guts and wouldn’t have cared what anyone else thought about him or his choices. He tossed the rule book into the trash heap and did it his way.”

The visual flourishes of “Three-Day Pass” could also be owed, in part, to Peebles’ lack of experience, which afforded him freedom to experiment. He had no feature filmmaking know-how, but he had support from professionals, including veteran French cinematographer Michel Kelber, whose work includes the films of Jean Renoir and René Clair.

A lengthy nightclub scene where Turner first meets Miriam incorporates jump cuts, freeze frames, extended first person/POV shots (foregrounding the “Black gaze”), split screens, and other showy gestures, all with no particular rhythm. This includes a double dolly shot as Turner enters the boite, coolly floating his way through the throng of patrons.

Nicole Berger, Harry Baird

Everett Collection

Today, the double dolly is a shot largely attributed to Spike Lee, who made it a signature. Even Van Peebles can’t claim ownership; it first became popular in the silent film era. Something else Lee may have inherited from Van Peebles: knowing how to turn commotion and controversy to his advantage. The ratings board couldn’t have done him a bigger favor by giving “Sweetback” an X rating, which he fully exploited.

Contemporary Black cinema doesn’t exist in a vacuum. In the effort to reconsider Black cinema in terms of cultural lineage, Criterion plans to re-release a restored “Sweetback,” as well as other Van Peebles films, including “Don’t Play Us Cheap,” “Watermelon Man,” and “Three-Day Pass,” along with son Mario’s 2003 film, “Baadasssss!”, starring as his father in a biopic about the making of “Sweetback.” All five films, plus Van Peebles’ mostly unseen shorts, will make up a single box set.

Van Peebles still has a sharp tongue and quick wit. “He’s good — a pleasant cat,” Mario said. “He told me the other day, ‘Boy, I’ve got CRS’. I asked, ‘What’s that, Daddy?’ He said, ‘Can’t Remember Shit’. He told me he can still process things quickly. It’s just that life seems to move slower than it used to.”

He’s not slowing down just yet. In development is an upcoming Broadway revival of his 1971 musical, “Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death,” scheduled for 2022, with Tony winner Kenny Leon directing.

The Hollywood he sidestepped 50 years ago to make films like “Three-Day Pass” and “Sweetback,” has changed for the better, but it’s been incremental. He has no regrets.

“He’s accomplished some amazing things in this life, and I’m happy that he gets to witness some of the changes happening in the industry,” Mario said. “But it’s not just for his sake; it’s healthy for us to see our stories told. If we don’t tell them, they become ‘his’ story. But, at the end of the day, dad has always been a maverick. We all can catch up with him, or not. That has been emblematic of all his work, not allowing himself to be pressured by outside forces. And it’s amazing.”

“The Story of a Three-Day Pass” is now in theaters and virtual cinemas.

The re-release isn’t tied to a milestone anniversary. “There’s a renewed interest in looking at Black history, given all that’s happened in the last few years, and you see it on the screen,” Mario said. “It’s also an anniversary of all things Van Peebles in a way: ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song’ celebrates its 50-year anniversary this year. And then, weirdly enough, 20 years later, I did ‘New Jack City’ in 1991. So, our anniversaries overlap — 30 years for me and 50 for dad. I think he did a lot of things that were ahead of their time, and people are still discovering the work decades later.”

The elder Van Peebles will be 89 on August 21. Overseeing his estate are Mario and his brother Max, who might recognize an urgency in collaborating with their father to reintroduce his life’s work. As the “godfather of independent Black cinema,” he’s an artist who may not have gotten his due. Mario said that boxing legend Muhammad Ali told him as much.

“He said, ‘I don’t think people recognize what your father did, when he put Black power on the screen. I put it on in the ring. He put it on the screen’,” Mario said. “But then Paul Robeson also asked, ‘When you buy into the paradigm and values of the people who would buy and sell you, what have you become?’ So how hungry are we for the dominant culture to acknowledge us? Melvin Van Peebles never thought, ‘My reward is going to be people acknowledging me, let alone people who are cultural trespassers.”

“Panther,” director Mario Van Peebles with father/writer Melvin Van Peebles on set, 1995.

GramercyPictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

By contrast, he recalled the satisfaction that came when his father was stopped in the street by a fan. “We were going for a stroll, and this brother came up to us with his family and said, ‘Excuse me, Mr. Van Peebles. I’ve got my son, my daughter, and my wife here, and I just wanted to say thank you. Sometimes I go to the movies and I’m entertained. Sometimes I learn something new. Sometimes I’m compelled to think. And sometimes I come out proud to be a man of color. With your movies, I get all of the above’. Now, that’s the reward,” Mario said.

With “Three-Day Pass,” Peebles didn’t set out to make a radical film. It’s a boy-meets-girl with a twist: the romance is interracial, which was very much a screen taboo at the time of its release — one year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia.

“Three-Day Pass” also subverted Hollywood interracial love stories like “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” a year prior, starring Sidney Poitier. Unlike the insufferably tame “Dinner,” Turner and Miriam dance intimately, drink, frolic on the beach, and even have sex. In 1968 America, that was gutsy filmmaking.

“He wasn’t at all interested in appealing to white people for his humanity, nor was he interested in making a movie about an upstanding ‘colored’ guy,” Mario said. “Turner is a regular dude, imperfect, trying to meet a girl, trying to get laid, trying to fall in love, trying to enjoy his life, like most men. So at a time when others were striving to be aspirational in terms of depicting Black people, Dad was just saying, ‘Yeah, that’s cool, but in my film, we’ll just have two everyday folks, who are trying to figure it out’. I remember him talking about getting to a place where we, as Black people, have the right to be ordinary.”

Before “Three-Day Pass,” there hadn’t been quite a film like it made by a Black filmmaker, with such freewheeling spontaneity. The few studio films that featured Black characters were often based on white liberal fantasies that fulfilled notions about what a “good Negro” should be. The Black lead was typically male and neutered — figuratively, of course.

Van Peebles shattered that illusion with films like “Three-Day Pass” and the incendiary “Sweet Sweetback” three years later. It became a reference point for radical, subversive Black cinema at a time when Black Americans were primed for it, post-Civil Rights movement.

“Dr. King was saying, ‘We must have freedom by peaceful means’, and brother Malcolm saying, ‘We must have freedom by any means’, and when America killed them both, Black folks got tired of being ‘colored’ and said, ‘Fuck that, we’re Black’,” Mario said. “And the subtext of ‘Black’ was, we were not trying to fit in, we were saying Black is beautiful, and we were going to have the Black Panther Party for self defense, and embrace the Black power mantra. And with all that in mind, it gave a whole different perspective on ‘Three-Day Pass’. Then, he came back with ‘Sweetback’ and put the idea of revolution on the screen for the first time.”

Van Peebles’ own story motivated him to pick up a camera. “It’s a film that, to some degree, must’ve been inspired by my parents’ relationship, in that I’m the product of said union,” Mario said. “Like Turner, he was in the service, in the Air Force, when he met my mom, who is white, in France, just like Turner and Miriam, and fell in love.

Often described as “New Wave-inspired,” star Nicole Berger previously appeared in short films by New Wave pioneers Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer, and co-starred in François Truffaut’s 1960 “Shoot the Piano Player.” Mario gives more credit to his father’s ingenuity and whim.

“He’s always had his own vibe and he took cinematic chances,” Mario said. “He had guts and wouldn’t have cared what anyone else thought about him or his choices. He tossed the rule book into the trash heap and did it his way.”

The visual flourishes of “Three-Day Pass” could also be owed, in part, to Peebles’ lack of experience, which afforded him freedom to experiment. He had no feature filmmaking know-how, but he had support from professionals, including veteran French cinematographer Michel Kelber, whose work includes the films of Jean Renoir and René Clair.

A lengthy nightclub scene where Turner first meets Miriam incorporates jump cuts, freeze frames, extended first person/POV shots (foregrounding the “Black gaze”), split screens, and other showy gestures, all with no particular rhythm. This includes a double dolly shot as Turner enters the boite, coolly floating his way through the throng of patrons.

Nicole Berger, Harry Baird

Everett Collection

Today, the double dolly is a shot largely attributed to Spike Lee, who made it a signature. Even Van Peebles can’t claim ownership; it first became popular in the silent film era. Something else Lee may have inherited from Van Peebles: knowing how to turn commotion and controversy to his advantage. The ratings board couldn’t have done him a bigger favor by giving “Sweetback” an X rating, which he fully exploited.

Contemporary Black cinema doesn’t exist in a vacuum. In the effort to reconsider Black cinema in terms of cultural lineage, Criterion plans to re-release a restored “Sweetback,” as well as other Van Peebles films, including “Don’t Play Us Cheap,” “Watermelon Man,” and “Three-Day Pass,” along with son Mario’s 2003 film, “Baadasssss!”, starring as his father in a biopic about the making of “Sweetback.” All five films, plus Van Peebles’ mostly unseen shorts, will make up a single box set.

Van Peebles still has a sharp tongue and quick wit. “He’s good — a pleasant cat,” Mario said. “He told me the other day, ‘Boy, I’ve got CRS’. I asked, ‘What’s that, Daddy?’ He said, ‘Can’t Remember Shit’. He told me he can still process things quickly. It’s just that life seems to move slower than it used to.”

He’s not slowing down just yet. In development is an upcoming Broadway revival of his 1971 musical, “Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death,” scheduled for 2022, with Tony winner Kenny Leon directing.

The Hollywood he sidestepped 50 years ago to make films like “Three-Day Pass” and “Sweetback,” has changed for the better, but it’s been incremental. He has no regrets.

“He’s accomplished some amazing things in this life, and I’m happy that he gets to witness some of the changes happening in the industry,” Mario said. “But it’s not just for his sake; it’s healthy for us to see our stories told. If we don’t tell them, they become ‘his’ story. But, at the end of the day, dad has always been a maverick. We all can catch up with him, or not. That has been emblematic of all his work, not allowing himself to be pressured by outside forces. And it’s amazing.”

“The Story of a Three-Day Pass” is now in theaters and virtual cinemas.