From the soul-searching of “My Winnipeg” to reimagining Bram Stoker as a dance movie for “Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary,” Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin has singularly made the movies he’s wanted to make for nearly four decades. There’s no one else quite like the cult director, who deploys tropes of Old Hollywood, from silent films to the talkies, in a language utterly his own. His first feature, “Tales from the Gimli Hospital,” had a midnight movie run after premiering in 1988 but has proven a rare find — until now, as Zeitgeist Films is releasing a new 4K restoration of the black-and-white, hour-long feature.

It’s one of Maddin’s nuttiest experiments and a blueprint for the sort of stories he’d go on to tell. Set in the eponymous unincorporated village in Manitoba, “Gimli” centers on a fisherman who brings a smallpox epidemic to his community. The film blends Icelandic-Canadian lore and real-life occurrences with historical fact-bending, a pre-Code sensibility, and wild, outrageous sequences of necrophilia and homoeroticism, as the ailing fisherman jockeys against another smallpox patient for the affections of the hospital’s nurses.

Like Jack Smith’s orgiastic “Flaming Creatures” from 1963, John Waters’ in-your-face filth fest “Pink Flamingos” from 1972, and David Lynch’s brain-blowing debut “Eraserhead” from 1977, “Gimli Hospital” announced an iconoclastic vision to the cult moviegoing world, and it deliberately flaunts its lack of good taste.

IndieWire spoke with the filmmaker about the restoration, his career, his thoughts on exhibition and how movies are consumed (“it would be nice if you weren’t checking your email, your Instagram, the casserole in the oven”), and the revealing time he lied to Björk during a 2007 Q&A in Iceland for “My Winnipeg.”

Next up, Maddin has the augmented reality project “Haunted Hotel” debuting in the London Film Festival’s Expanded section. He hopes to next bring the project — an interactive, moving paper collage of clippings from Maddin’s own nerdy personal archives — to the states.

IndieWire: Having watched your movies for a couple of decades going back to “The Saddest Music in the World,” I was still surprised by “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” because I’d never seen it. Watching the screener on my laptop was still a crazy experience.

Guy Maddin: Almost my entire film education has been on VHS tapes on a crummy TV, in the ‘80s, and since then, I have the Criterion Channel, but I just watch it all on my laptop. I edited “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” on a little screen. It was very murky, so I am used to not just watching other people’s movies but my own on a tiny little viewfinder the size of a laptop. It was murky and flickery. As a matter of fact, I really only saw the movie once, properly, on a big screen when it premiered in 1988 and then once properly again 34 years later at TIFF. You really do see a lot more detail in the picture than what I’d ever seen before. The restoration technique I’m a big fan of, of the 4K transfer. You get more of what’s on the negative than was ever on the original print back in the day. There’s far more color-grading.

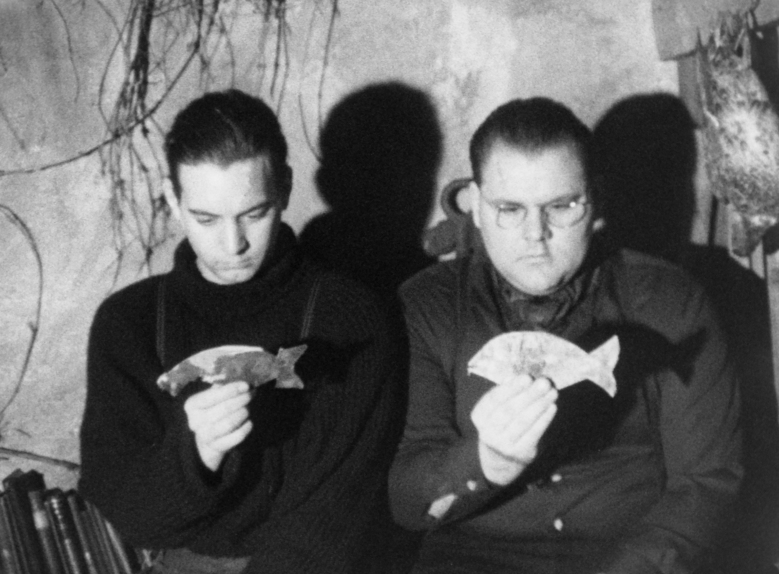

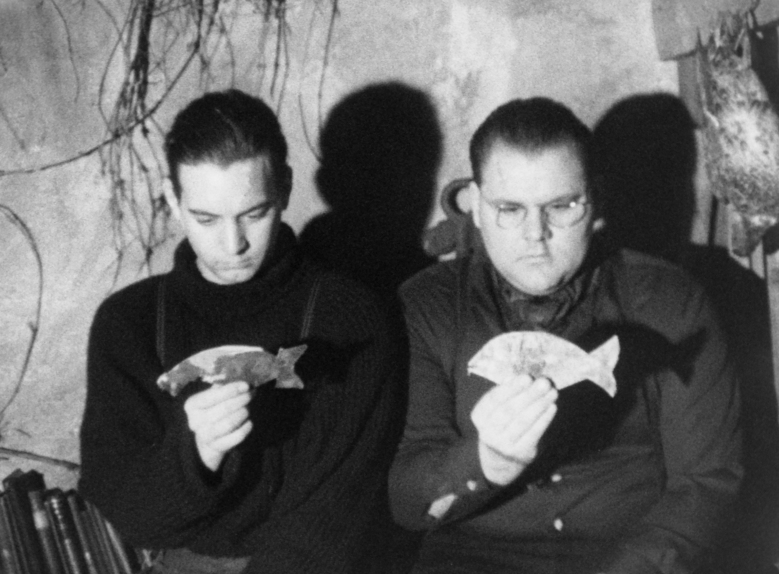

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital”

Courtesy Zeitgeist Films

Originally, this movie was rejected by the Toronto Film Festival. Obviously, you’ve had much of your work presented at TIFF since, so of course, they love you now, but did it feel vindicating to have “Gimli” finally screen there?

I’ve not only got a great relationship with TIFF — they’ve shown every one of my movies since — but I’ve become friends with people on the selection committee that rejected it. I had a ringside seat to the whole process of rejection. I used the anger to try and make a better movie next time. Piers Handling, even though he’s retired as the director of TIFF, showed up at the recent screening and gave me a hug, and that was my chance to go, “In your face, Handling!” I made him stand up and acknowledge his presence. The restoration’s premiere took on the aromas of a pro-wrestling match for a few seconds, and then dignity was restored.

As a first feature, it’s very formally experimental and alienating to certain corners of the audience, especially with its pre-Code sensibility. You’re also working with Icelandic lore. Was it hard to convince people to trust your vision?

I don’t think I did get any grant money. My aunt passed away and left me $40,000, and I used half of it to make the movie, and the other half to live for the 18 months it took me to make it. I had a lot of confidence making it, so the only people I had to convince were actors, and most I used were non-actors… or pals of mine. Or relatives. I don’t think anyone turned me down. Everyone said, “OK. Sounds like fun.” Convincing them to watch the movie later would’ve been a hard thing to do. Once it was finished and just a random audience showed up for it at film festivals, there’s a certain significant percentage of the average moviegoing audience that this isn’t for. It had a walkout rate of 50-80 percent back in the day. It’s nice to see that audiences know what to expect from me to a greater degree now, and they know how to read between the lines. I like to think I was three and a half decades ahead of the film world.

What was the lifespan when “Gimli” first came out? It became a midnight movie in the classic sense, where there were regular rep screenings.

In America, it was picked up by Ben Barenholtz, who was famous for being the distributor of “Eraserhead.” He had a singular plan of attack for getting “Eraserhead” out in the world. He played it only Saturdays at midnight and placed no ads for the movie except a single line: “Eraserhead. Midnight” in the personal columns of the Village Voice or something. It was very organic, very sneaky, very wily, and the movie is so powerful, so emotionally urgent, way more so than “Gimli Hospital” that it eventually did exactly what he hoped it would do: It gathered so much word-of-mouth momentum. He tried a similar strategy with “Gimli Hospital,” but times had changed. I love “Eraserhead” and really hope people come out to see my film, but it isn’t “Eraserhead.” It’s something else. You can’t plan cult hits. It did play for a year or two on the midnight circuit, but never took off in a big way. It’s a different thing. I had different plans. David Lynch and I went in different directions. Still never met him, strangely.

There are filmmakers who are very admonishing of the “at home” experience, perhaps because it gives too much power to the viewer, and some of them want control, they want you in the theater. Do you have more of a democratic philosophy of how movies should be consumed?

I know someone’s going to be checking their email, whether in their living room or sneakily in the theater. “Gimli Hospital” is a trippy atmosphere piece. There is a plot there but it’s not like a Preston Sturges, plot-driven picture. It’s a head space thing, so it would be nice if you weren’t checking your email, your Instagram, the casserole in the oven. But I’m not that naïve. This is just the way movies are watched now. While editing it, I never had a chance to see the rushes on the big screen or an actual cut of the movie on the big screen. I only saw the movie at its premiere, which was at a film festival in Montreal. It premiered on a bedsheet draped over a volleyball net in Gimli [before the festival]. The screening in Gimli was the best, because most of the people were watching on the lawn. Cars would drive by. Mayflies and fishflies would land on the net. By the end of the movie, half the people had fallen asleep from drinking too much or just sheer ennui. These people weren’t cineastes. They were just my neighbors at the lake. They weren’t all excited about the German Expressionist tropes and talkie vocabulary I was employing on behalf of telling this story about the local smallpox epidemic.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital”

Courtesy Zeitgeist Films

What chord did the movie strike locally because you depict this smallpox epidemic that was very real?

Journalists hated the movie and said it misrepresented historical fact, but that was my point. I wanted to mythologize Gimli by giving it the old Hollywood treatment. No one’s ever accused Cecil B. DeMille or any of those old-time filmmakers of concerning themselves with historic accuracy; they were there to make spectacles. A lot of your first encounters with history as a kid are through hyperbolic, hyper-mythologizing film accounts, and then if you’re interested, you can read up on what really happened, and then as an adult be repulsed by the movie depictions. I wanted to make a Hollywood movie…of an Icelandic saga about a historical, real-life occurrence. For what it’s worth, I succeeded, but who knows.

This has elements of a Hollywood movie, but there’s this reveling in depravity going on, which is of course part of Old Hollywood. There’s necrophilia, and homoeroticism. Did you set out to defy good taste intentionally in the John Waters kind of way?

The feature films being made in Canada in the ‘80s were nothing but good taste. A lot of the dramas were dedicated accounts of historical events, and they were just so aridly presented. It’s like Canadian filmmakers, instead of picking up a pair of binoculars and making things look bigger than life, had the binoculars backwards and were determined to make real-life events look smaller. “You’re holding the binoculars up wrong,” I felt like screaming.

There was a book written by the Gimli Kinsmen women’s guild. It’s just an oral history of accounts of what it was like in the 1870s. That was my research. Then I grew up in an Icelandic beauty salon in the west end of Winnipeg, and most of the customers were Icelandic-Canadian, and you could hear them yelling out in their sing-songy accents over the roar of the hairdryers and the chain-smoking. These stories seemed worth documenting.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital”

Courtesy Zeitgeist Films

How did you approach making “Gimli” as a black-and-white silent movie, preserving many of the elements of the era, that also introduces sound and becomes something more contemporary?

Silent movies are one big step toward the fairytale. The part-talkie gave me the freedom to invoke silent movie folklore flavors, but it also gave me the opportunity to have people speak to contribute some lyricism or exposition. The part-talkie was made in the pre-Code years, so that would enable you to have a little bit of nudity, a little bit of suggested homoeroticism and other perversions. I don’t mean homoeroticism is a perversion! I’m the homoerotic one anyway. Necrophilia, let’s call that one a perversion. I’ll take some guff from any necrophiliac that steps forward to complain about the insensitivity of my words right now.

You could put subjects that became verboten after 1934 in Hollywood, like homoeroticism, and it had to be so obliquely suggested, and that was exquisite because there was a gay code. So many screenwriters and directors were gay in Hollywood, of course, and they were dying to reveal that so they just developed a code for it, and I could read it and speak it by the time I was six years old. It was fun to deploy that code in an era when no one was using the code anymore. You could just have gay characters, so it was nice to use the code when treating your gay subject matter.

What prompted the restoration and wanting to go back to this movie? There’s something disassociating about revisiting past work, but it can tell you something about yourself now.

I don’t know if I’m matured that much since making this, but I did have a lot of fun making it, and that’s evident on the screen for me. But I’m more sensitive and sophisticated — that sounds horrible to say about yourself, it sounds conceited, and it’s not even true! I like lowbrow garbage now just as much as I ever did. I can’t take myself seriously for even long enough to finish a sentence. It’s ridiculous. I need to be flat-tired instantly. I took it about myself when I was mythologizing Winnipeg in “My Winnipeg” in 2007, in Q&As, people would ask me if a certain part of the movie was true. They were suspicious I was making up a lot of this movie. I promised myself that I would always alternate answers, that I would say, “yes it’s true,” at one Q&A, and then the next would describe it as made-up. I thought I was being so mischievous, but then I learned the lies you choose to tell in a Q&A, not to mislead voters or readers, just to be mischievous, to create a myth about your subject matter, the way you curate your lies on the fly…

In “My Winnipeg,” there’s a scene where horses have been frozen in a river, so there’s 11 horse heads sticking out. I was at a screening in Reykjavik once, and I heard a woman’s voice asking, “Is it true about the horses?” I looked and it was Björk asking the question. In that couple of seconds, I was thinking, “Good god, it’s Björk! I can’t lie to Björk!” Then I went, “No, I must lie more to Björk.” I expanded on the horse crap that’s in the film until it was an even more elaborate thing. She invited me up for a whale burger after.

There’s an act of curation where you’re trying on a few lies for size in your head before you blurt them out, and that’s very revealing, and you might as well just be telling the truth. It’s the kind of lie that you choose to tell that profiles you.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital” screens at IFC Center this weekend in New York, including Q&As with the filmmaker on October 14 and 15 and his short film “The Heart of the World.” Visit IFC Center’s website for ticket information.

It’s one of Maddin’s nuttiest experiments and a blueprint for the sort of stories he’d go on to tell. Set in the eponymous unincorporated village in Manitoba, “Gimli” centers on a fisherman who brings a smallpox epidemic to his community. The film blends Icelandic-Canadian lore and real-life occurrences with historical fact-bending, a pre-Code sensibility, and wild, outrageous sequences of necrophilia and homoeroticism, as the ailing fisherman jockeys against another smallpox patient for the affections of the hospital’s nurses.

Like Jack Smith’s orgiastic “Flaming Creatures” from 1963, John Waters’ in-your-face filth fest “Pink Flamingos” from 1972, and David Lynch’s brain-blowing debut “Eraserhead” from 1977, “Gimli Hospital” announced an iconoclastic vision to the cult moviegoing world, and it deliberately flaunts its lack of good taste.

IndieWire spoke with the filmmaker about the restoration, his career, his thoughts on exhibition and how movies are consumed (“it would be nice if you weren’t checking your email, your Instagram, the casserole in the oven”), and the revealing time he lied to Björk during a 2007 Q&A in Iceland for “My Winnipeg.”

Next up, Maddin has the augmented reality project “Haunted Hotel” debuting in the London Film Festival’s Expanded section. He hopes to next bring the project — an interactive, moving paper collage of clippings from Maddin’s own nerdy personal archives — to the states.

IndieWire: Having watched your movies for a couple of decades going back to “The Saddest Music in the World,” I was still surprised by “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” because I’d never seen it. Watching the screener on my laptop was still a crazy experience.

Guy Maddin: Almost my entire film education has been on VHS tapes on a crummy TV, in the ‘80s, and since then, I have the Criterion Channel, but I just watch it all on my laptop. I edited “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” on a little screen. It was very murky, so I am used to not just watching other people’s movies but my own on a tiny little viewfinder the size of a laptop. It was murky and flickery. As a matter of fact, I really only saw the movie once, properly, on a big screen when it premiered in 1988 and then once properly again 34 years later at TIFF. You really do see a lot more detail in the picture than what I’d ever seen before. The restoration technique I’m a big fan of, of the 4K transfer. You get more of what’s on the negative than was ever on the original print back in the day. There’s far more color-grading.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital”

Courtesy Zeitgeist Films

Originally, this movie was rejected by the Toronto Film Festival. Obviously, you’ve had much of your work presented at TIFF since, so of course, they love you now, but did it feel vindicating to have “Gimli” finally screen there?

I’ve not only got a great relationship with TIFF — they’ve shown every one of my movies since — but I’ve become friends with people on the selection committee that rejected it. I had a ringside seat to the whole process of rejection. I used the anger to try and make a better movie next time. Piers Handling, even though he’s retired as the director of TIFF, showed up at the recent screening and gave me a hug, and that was my chance to go, “In your face, Handling!” I made him stand up and acknowledge his presence. The restoration’s premiere took on the aromas of a pro-wrestling match for a few seconds, and then dignity was restored.

As a first feature, it’s very formally experimental and alienating to certain corners of the audience, especially with its pre-Code sensibility. You’re also working with Icelandic lore. Was it hard to convince people to trust your vision?

I don’t think I did get any grant money. My aunt passed away and left me $40,000, and I used half of it to make the movie, and the other half to live for the 18 months it took me to make it. I had a lot of confidence making it, so the only people I had to convince were actors, and most I used were non-actors… or pals of mine. Or relatives. I don’t think anyone turned me down. Everyone said, “OK. Sounds like fun.” Convincing them to watch the movie later would’ve been a hard thing to do. Once it was finished and just a random audience showed up for it at film festivals, there’s a certain significant percentage of the average moviegoing audience that this isn’t for. It had a walkout rate of 50-80 percent back in the day. It’s nice to see that audiences know what to expect from me to a greater degree now, and they know how to read between the lines. I like to think I was three and a half decades ahead of the film world.

What was the lifespan when “Gimli” first came out? It became a midnight movie in the classic sense, where there were regular rep screenings.

In America, it was picked up by Ben Barenholtz, who was famous for being the distributor of “Eraserhead.” He had a singular plan of attack for getting “Eraserhead” out in the world. He played it only Saturdays at midnight and placed no ads for the movie except a single line: “Eraserhead. Midnight” in the personal columns of the Village Voice or something. It was very organic, very sneaky, very wily, and the movie is so powerful, so emotionally urgent, way more so than “Gimli Hospital” that it eventually did exactly what he hoped it would do: It gathered so much word-of-mouth momentum. He tried a similar strategy with “Gimli Hospital,” but times had changed. I love “Eraserhead” and really hope people come out to see my film, but it isn’t “Eraserhead.” It’s something else. You can’t plan cult hits. It did play for a year or two on the midnight circuit, but never took off in a big way. It’s a different thing. I had different plans. David Lynch and I went in different directions. Still never met him, strangely.

There are filmmakers who are very admonishing of the “at home” experience, perhaps because it gives too much power to the viewer, and some of them want control, they want you in the theater. Do you have more of a democratic philosophy of how movies should be consumed?

I know someone’s going to be checking their email, whether in their living room or sneakily in the theater. “Gimli Hospital” is a trippy atmosphere piece. There is a plot there but it’s not like a Preston Sturges, plot-driven picture. It’s a head space thing, so it would be nice if you weren’t checking your email, your Instagram, the casserole in the oven. But I’m not that naïve. This is just the way movies are watched now. While editing it, I never had a chance to see the rushes on the big screen or an actual cut of the movie on the big screen. I only saw the movie at its premiere, which was at a film festival in Montreal. It premiered on a bedsheet draped over a volleyball net in Gimli [before the festival]. The screening in Gimli was the best, because most of the people were watching on the lawn. Cars would drive by. Mayflies and fishflies would land on the net. By the end of the movie, half the people had fallen asleep from drinking too much or just sheer ennui. These people weren’t cineastes. They were just my neighbors at the lake. They weren’t all excited about the German Expressionist tropes and talkie vocabulary I was employing on behalf of telling this story about the local smallpox epidemic.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital”

Courtesy Zeitgeist Films

What chord did the movie strike locally because you depict this smallpox epidemic that was very real?

Journalists hated the movie and said it misrepresented historical fact, but that was my point. I wanted to mythologize Gimli by giving it the old Hollywood treatment. No one’s ever accused Cecil B. DeMille or any of those old-time filmmakers of concerning themselves with historic accuracy; they were there to make spectacles. A lot of your first encounters with history as a kid are through hyperbolic, hyper-mythologizing film accounts, and then if you’re interested, you can read up on what really happened, and then as an adult be repulsed by the movie depictions. I wanted to make a Hollywood movie…of an Icelandic saga about a historical, real-life occurrence. For what it’s worth, I succeeded, but who knows.

This has elements of a Hollywood movie, but there’s this reveling in depravity going on, which is of course part of Old Hollywood. There’s necrophilia, and homoeroticism. Did you set out to defy good taste intentionally in the John Waters kind of way?

The feature films being made in Canada in the ‘80s were nothing but good taste. A lot of the dramas were dedicated accounts of historical events, and they were just so aridly presented. It’s like Canadian filmmakers, instead of picking up a pair of binoculars and making things look bigger than life, had the binoculars backwards and were determined to make real-life events look smaller. “You’re holding the binoculars up wrong,” I felt like screaming.

There was a book written by the Gimli Kinsmen women’s guild. It’s just an oral history of accounts of what it was like in the 1870s. That was my research. Then I grew up in an Icelandic beauty salon in the west end of Winnipeg, and most of the customers were Icelandic-Canadian, and you could hear them yelling out in their sing-songy accents over the roar of the hairdryers and the chain-smoking. These stories seemed worth documenting.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital”

Courtesy Zeitgeist Films

How did you approach making “Gimli” as a black-and-white silent movie, preserving many of the elements of the era, that also introduces sound and becomes something more contemporary?

Silent movies are one big step toward the fairytale. The part-talkie gave me the freedom to invoke silent movie folklore flavors, but it also gave me the opportunity to have people speak to contribute some lyricism or exposition. The part-talkie was made in the pre-Code years, so that would enable you to have a little bit of nudity, a little bit of suggested homoeroticism and other perversions. I don’t mean homoeroticism is a perversion! I’m the homoerotic one anyway. Necrophilia, let’s call that one a perversion. I’ll take some guff from any necrophiliac that steps forward to complain about the insensitivity of my words right now.

You could put subjects that became verboten after 1934 in Hollywood, like homoeroticism, and it had to be so obliquely suggested, and that was exquisite because there was a gay code. So many screenwriters and directors were gay in Hollywood, of course, and they were dying to reveal that so they just developed a code for it, and I could read it and speak it by the time I was six years old. It was fun to deploy that code in an era when no one was using the code anymore. You could just have gay characters, so it was nice to use the code when treating your gay subject matter.

What prompted the restoration and wanting to go back to this movie? There’s something disassociating about revisiting past work, but it can tell you something about yourself now.

I don’t know if I’m matured that much since making this, but I did have a lot of fun making it, and that’s evident on the screen for me. But I’m more sensitive and sophisticated — that sounds horrible to say about yourself, it sounds conceited, and it’s not even true! I like lowbrow garbage now just as much as I ever did. I can’t take myself seriously for even long enough to finish a sentence. It’s ridiculous. I need to be flat-tired instantly. I took it about myself when I was mythologizing Winnipeg in “My Winnipeg” in 2007, in Q&As, people would ask me if a certain part of the movie was true. They were suspicious I was making up a lot of this movie. I promised myself that I would always alternate answers, that I would say, “yes it’s true,” at one Q&A, and then the next would describe it as made-up. I thought I was being so mischievous, but then I learned the lies you choose to tell in a Q&A, not to mislead voters or readers, just to be mischievous, to create a myth about your subject matter, the way you curate your lies on the fly…

In “My Winnipeg,” there’s a scene where horses have been frozen in a river, so there’s 11 horse heads sticking out. I was at a screening in Reykjavik once, and I heard a woman’s voice asking, “Is it true about the horses?” I looked and it was Björk asking the question. In that couple of seconds, I was thinking, “Good god, it’s Björk! I can’t lie to Björk!” Then I went, “No, I must lie more to Björk.” I expanded on the horse crap that’s in the film until it was an even more elaborate thing. She invited me up for a whale burger after.

There’s an act of curation where you’re trying on a few lies for size in your head before you blurt them out, and that’s very revealing, and you might as well just be telling the truth. It’s the kind of lie that you choose to tell that profiles you.

“Tales from the Gimli Hospital” screens at IFC Center this weekend in New York, including Q&As with the filmmaker on October 14 and 15 and his short film “The Heart of the World.” Visit IFC Center’s website for ticket information.